Crystal Clear

Crystal Clear: How Harvey K. Littleton’s vision sparked an artistic revolution and ignited the Studio Glass Movement.

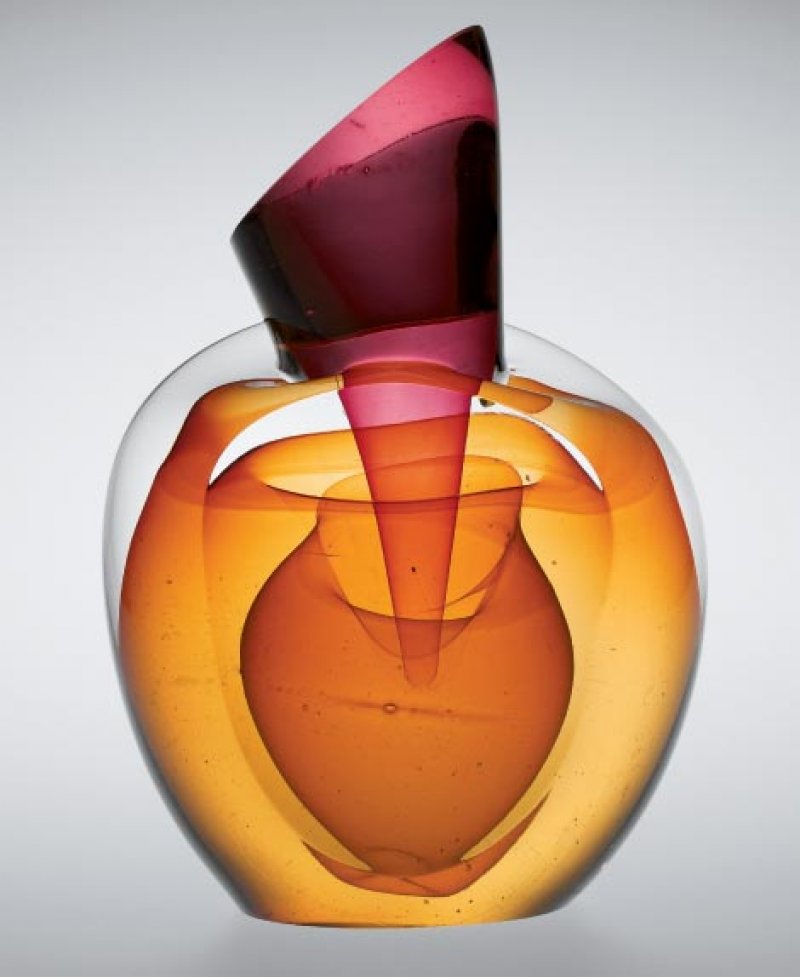

Every week, hundreds of cars pass Harvey K. Littleton’s house and studio near Spruce Pine along the Blue Ridge Parkway. Many of the passers-by know they’re near a colony of artists at Penland School of Crafts, but most are unaware that among them is a man who sparked an art revolution. Often called the father of the American Studio Glass Movement, Harvey began making glass art 50 years ago from a fiery furnace he built on his farm in Wisconsin. Defying accepted wisdom that glass could not be designed and crafted outside a factory setting, he opened the medium as a form of expression for a generation of artists—unleashing the crazy tendrils in works by internationally renowned glass artist Dale Chihuly and explosive colors in organic forms by Marvin Lipofsky.

“Without a doubt, Harvey Littleton was the force behind the Studio Glass Movement. Without him, my career wouldn’t exist,” Chihuly is quoted in Harvey K. Littleton: A Life in Glass by Joan Falconer Byrd, a Western Carolina University professor ceramics and former student of Harvey’s.

“The idea that everybody else thought was crazy—he wasn’t fazed by that,” says glass artist Kate Vogel, Harvey’s daughter-in-law. “He just kept plugging away.” She and her husband, John Littleton, are accomplished glass artists who live in Bakersville.

In recognition of Harvey’s work and the 50th anniversary of the American Studio Glass Movement, museums across the country, including the Asheville Art Museum and Fine Art Museum at WCU, are staging exhibitions this year. Now advanced in age, the artist does not grant interviews, but Byrd’s book offers insight about his artistic path—from a child who often visited his father’s workplace, Corning Glass Works, to the man who blended science and art for the purpose of deeper expression.

Born in 1922, Harvey grew up in Corning, New York, home of Corning Glass Works. His father, Jesse “J.T.” Littleton, director of research and development there, held numerous patents. Harvey’s mother, Bessie Cook Littleton, was the first person to cook in Pyrex, baking a cake in a pan that her husband brought home to test. “Harvey grew up with innovation being the norm,” Vogel says.

Harvey worked at Corning Glass Works during two summer breaks from the University of Michigan, where he was studying industrial design. After graduation, he proposed that the company establish an experimental glass studio, but was turned down. “My idea was that there ought to be continuing, ongoing, aesthetic experimentation in material apart from production,” Harvey is quoted in Byrd’s book. “They believed that architects made the best designers, where you made your designs on paper and didn’t fool around with the material. Whereas I thought form was born in the material and in the hands of the artist, and that a pencil was a pretty damned poor substitute and that it only results in a very obvious and simplistic solution.”

Harvey attended graduate school at Cranbrook Academy of Art in Michigan, where he studied ceramics. In 1951, he landed a teaching position at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Byrd, then a graduate student, studied with him there. While researching her book, she came to understand that Harvey was too ambitious to be satisfied creating functional pieces of pottery. He wanted to work in glass, and he wanted it to be sculpture, she says.

The prevailing thought at the time was glass could be shaped only in industrial furnaces. Building a small furnace on his farm near Madison, Harvey began mixing, melting, and blowing glass. In 1962, in what is considered the beginning of the American Studio Glass Movement, he conducted two important glass-blowing workshops at the Toledo Museum of Art, enlisting the help of glass engineer Dominick Labino.

The first batch of glass didn’t melt as Harvey and Labino had hoped. Labino revised the melting process and brought in glass marbles he had developed for the production of fiberglass. The changes yielded a pliable molten glass that could be easily blown. The first forms were simple, clear vessels, but the lessons learned pumped life into a new vein of art.

The workshops turned out to be a resounding success, proving that glass could be worked on a small scale, and Harvey became studio glass’ leading advocate. Blowing the viscous material is “the most dynamic method of working with glass, a medium where you have to make instantaneous decisions. Students like that kind of energy,” Byrd says. “Harvey knew that if it would catch on, it would catch on like wildfire.”

In the year after those first workshops, Harvey taught 32 others. “This is a man who is obsessed,” Vogel says with a laugh. “He jokingly says he was the evangelist preacher going out to recruit people, but he was trying to convert them to glass.”

In the fall of 1962, the University of Wisconsin allowed Harvey to launch a graduate course in glass blowing, the first of its kind in the United States. The program set the stage for students to explore new techniques and spread their knowledge across the country. Chihuly, a leader in the avant-garde fine art glass movement, would go on to establish the glass program at Rhode Island School of Design and cofound the Pilchuck Glass School in Washington. Lipofsky, a California glass artist who refined his skills in Europe’s established glass factories, and Fritz Dreisbach, a Washington artist who in 2002 received the Glass Art Society’s lifetime achievement award, were also Harvey’s students.

“What’s quite extraordinary are the strides made between 1962 and 1970 as these artists, who were also chemists and experimenters, learned about the medium,” says Pamela Myers, executive director of the Asheville Art Museum. “In short order, you have these elegant glass bodies in shapes and forms that clearly demonstrated the experimentation and that the learning curve was really steep. It really just exploded.”

Harvey’s work drew national and international attention. In 1963, the Museum of Modern Art acquired a clear, cascading sculpture—a piece aesthetically distant from the colorful, balletic arcs that he would create later in his career. By the time he was asked to judge the Toledo Glass National in 1966, there were 15 higher education courses in glass craftsmanship in the country. Within a decade, more than 50 U.S. colleges and universities offered glass programs, according to Craft in America, a Los Angeles-based nonprofit organization.

In 1965, Harvey was asked to start a program at Penland School of Crafts. Already committed to spending the summer in Germany with glass sculptor Erwin Eisch, he recommended student Bill Boysen, who built the first glass studio at the school. Once established, the program would attract outstanding glassblowers as teachers and artists-in-residence.

Harvey didn’t arrive in Western North Carolina until 1977, when Byrd, then teaching at WCU, invited him to speak at an exhibition of glass art. While here, he and his wife, Bess, visited friends in the Penland area, and within a year, they moved to the mountains.

The half dozen glass artists in the area at the time were working on crude equipment, according to Bakersville glass artist Richard Ritter. Harvey offered them the use of his studio, which housed extensive cold-working equipment. Renowned artists such as Mark Peiser, Rob Levin, and Ritter came to refine and finish their blown works, and students were invited to study his historical and contemporary glass collections. “Harvey Littleton’s move to Spruce Pine fueled the fire for studio glass in North Carolina,” explains Denise Drury, interim director of the WCU art museum.

Working hot, heavy glass became too much for Harvey in 1990, so he revived his efforts in vitreography, a science he’d advanced that uses thick sheets of glass to make art prints. The results were so encouraging that Harvey installed an etching press in his Spruce Pine studio, hiring a full-time master printer and inviting artists such as Chihuly, Eisch, Ann Wolff, and Penland potter Cynthia Bringle to explore the process.

Though he never taught at Penland, instead serving on the board of trustees, the move to Spruce Pine satisfied the educator in him as much as the artist, according to Byrd. “He got a charge out of being the teacher,” she says. “He said you don’t really have anything if you do it only for yourself.”