Seeds of Change

Seeds of Change: Utopian Seed Project tackles the climate crisis through crop diversity

Crop Diversity - While researching his James Beard Award-winning book, The Whole Okra, Chris Smith propagated more than 70 varieties of the plant in Leicester near Asheville; (inset) Smith with a freshly dug and rather large yacon (aka Bolivian sunroot), a sweet potato-like tuber from South America.

If you flip through a typical seed catalogue or shop at a grocery store, you might think there’s one variety of okra that always produces identical green pods. But step into the Utopian Seed Project’s okra patch and it becomes clear that there’s a rainbow of different varieties, each with its own lush color, distinct growth habits, and nuanced flavor.

The Utopian Seed Project’s founder, Chris Smith, remembers feeling a little stunned while standing beside the 76 varieties of okra he planted in Leicester while working on his James Beard Award-winning book The Whole Okra. As a longtime employee of the Asheville-based heirloom seed company, Sow True Seed, Smith was well acquainted with a wide range of varieties, but he was still in awe of the genetic diversity on display. An heirloom called Aunt Hettie’s Red had plump burgundy pods and outstanding flavor; a Mexican variety named Guarijio Nescafe was filled with seeds that could be roasted and brewed like coffee.

Growing Hope - The project’s push to diversify area crops has a home base at Franny’s Farm (left). Right, the pawpaw, from a family of tropical fruits.

A spark of inspiration was kindled in that field of okra, and Smith formed the Utopian Seed Project in 2019. It’s a hands-in-the dirt nonprofit dedicated to trialing crops in the Southeast to support genetic diversity in farming and food. These trials involve planting several varieties of a crop to record and compare how quickly they grow, how they stand up to weather and pests, and the qualities of the food they produce.

The crop trials are fascinating and beautiful to see in the field, but they are also a step toward combating the climate crisis. The current global food system relies on monoculture to produce a limited number of varieties that can be grown efficiently and appear fresh after traveling thousands of miles. If these limited varieties can’t survive the warming temperatures, new diseases, and extreme weather events brought on by climate change, there could be global shortages and some crops like bananas could even become extinct.

Researching dozens of varieties that can adapt to these conditions in different ways offers a framework for genetic diversity and strengthens the resiliency of the food system. Varietal diversity means a tight-knit farming community like Western North Carolina has more options if one crop fails due to the effects of climate change. Farmers can look at the Utopian Seed Project’s research and communicate with each other to choose varieties that can adapt to regional changes.

“It’s a very complicated problem to solve,” says Smith, “but I think if we can start by having people knowing and understanding and enjoying and engaging with their local micro-regional food systems, then just having that knowledge can be empowering.”

Testing, Testing - The project is experimenting with chaya, aka tree spinach (left), which is popular in Central America, and tumeric (right).

Going tropical

A warmer climate means some tropical plants can be grown in temperate areas like WNC for the first time. The Utopian Seed Project is triailing crops like arrowroot, bambara groundnuts, and pigeon peas to document how they grow in this region as annual plants. The goal is for them to be grown outdoors and produce seeds or tubers that can be planted the following season.

Over a decade ago, legendary seed saver and Utopian Seed Project board member Yanna Fishman introduced some local farmers to the idea of growing crops like ginger and turmeric. Now farms throughout the region plant them as annuals, and people eagerly await the arrival of these tropical foods at farmers markets. The Utopian Seed Project hopes that the same could play out with water chestnuts, chayote squash, and Andean root vegetables like oca and yacon.

Smith says some of these tropical crops will become easier to grow as climate change makes it more difficult to cultivate traditional produce. He points to taro as a particularly promising vegetable because it is highly productive and grows well as an annual. Its leaves are delicious, and its starchy purple corms (or tubers) can be roasted or boiled to produce a sweet, nutty flavor.

“We’re kind of hedging our bets by learning how to grow and eat and have them be accepted as food crops well ahead of time so that we’ve got sustainable food systems going into a very different climate future,” Smith says.

The Utopian Seed Project also aims to raise awareness and enthusiasm for wild and native crops that are sometimes underutilized. Pawpaws are prized for their bright tropical flavor, but these native fruit trees can be hard to track down in the wild. A long-term goal is to establish a pawpaw orchard where visitors can taste the fruit and bring seedlings home to plant in their yards.

Chef Ashleigh Shanti and Smith sort varieties of collards. Learn how to become involved with the project at theutopianseedproject.org.

Trial to table

Encouraging local eaters to embrace different flavors and textures is important to the success of this project. A healthy crop of taro isn’t worth much if farmers market shoppers won’t buy it; it doesn’t make sense to grow fresh arrowroot if people don’t know how to prepare it. That’s why the Utopian Seed Project is working with chefs to spread the word about these crops and document their flavors.

Chef Ashleigh Shanti, former chef de cuisine at Benne on Eagle in Asheville and a Utopian Seed Project board member, was one of the first people to taste the results of the heirloom collards trials. Smith brought her some of the 20 varieties they grew, and Shanti gave feedback on how they tasted and ways a chef or home cook could use them in the kitchen.

She selected an especially tender variety for raw salads, while hearty stems inspired tangy, crunchy collard pickles. “Whenever you talk to chefs about flavor, they just have a whole different lexicon to apply to food,” Smith says.

Chefs aren’t the only ones embracing the nuances of these vegetables. The Utopian Seed Project hosts Trial to Table Dinners at Franny’s Farm in Leicester, where people can walk around the farm where the crop trials take place.

These casual buffet dinners feature dishes made with the vegetables the Utopian Seed Project is growing and researching that year. Inspired by 19th-century references to arrowroot pudding, chef and farmer Jamie Swofford and baker Keia Mastrianni created a modern take on arrowroot pudding that won over the crowd at a 2019 event.

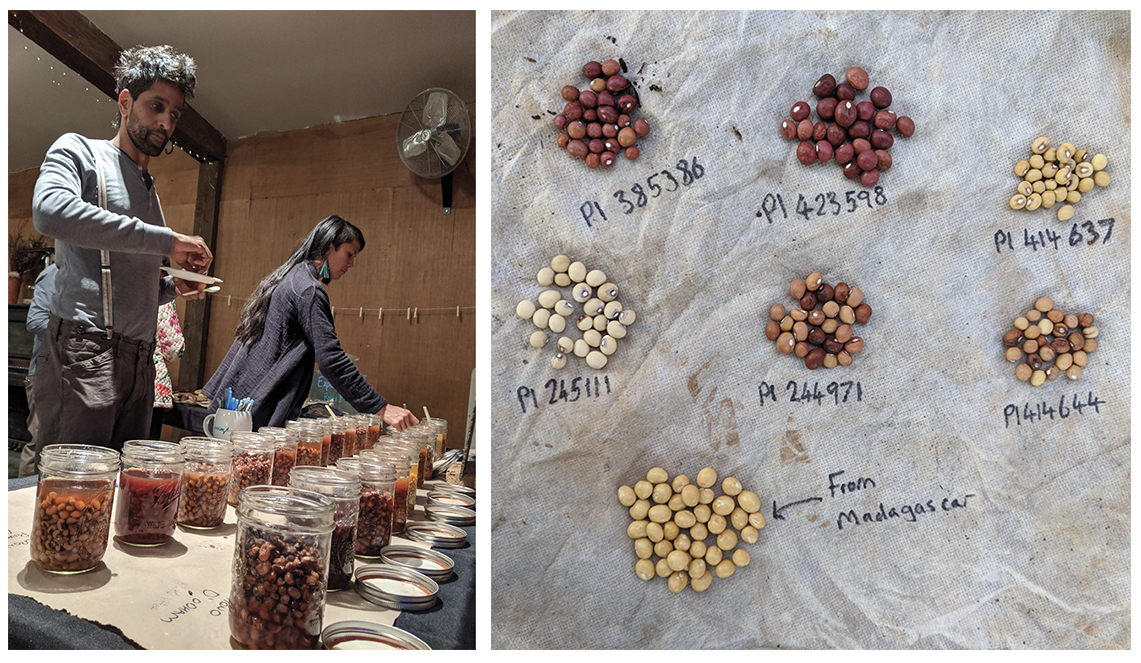

Seedy Business - The bambera groundnut is native to West Africa and has multiple food and beverage uses.

Guests also had the opportunity to contribute to the research by taste testing different varieties and providing feedback on their flavors and textures. At the last dinner before the pandemic, they placed jars of 40 different varieties of Southern peas on a strip of brown paper. People went down the tasting line and wrote their observations. Smith started to see patterns when he entered these keywords in a database. Some peas were consistently described as mild or earthy or sweet, and this information will help the Utopian Seed Project decide which varieties to pursue in future trials.

As the climate crisis becomes ever more urgent, Smith believes one way to change the world is to change people’s relationships with food. When people understand the global food system, embrace local alternatives, and develop an appreciation for different varieties, it can shift their perspectives and choices.

He hopes the Utopian Seed Project’s work will contribute to a world where “a whole lot of people have woken up to the possibilities of food and are actually engaging in their own food sovereignty.” As optimistic as a pocketful of seeds in spring, Smith is working toward a resilient food and farming utopia in Western North Carolina and beyond.