Bluegrass

Bluegrass:

My conversion to bluegrass music took place nearly 20 years ago at a small, private college east of Asheville. It was spring, near dusk, and I’d followed the sound of a banjo back to its source, through the courtyard of a neighboring dorm and down a hallway to the entrance of a dimly lit room.

The scene that resolved after a moment was of four guys in a fog of body odor, all of them dressed in flannel shirts and work pants, hunched over their instruments like supplicants at midnight mass. I stood in the doorway for a while, listening. I probably stayed longer than I should have. After a time, it came out that, yes, I played guitar a little, and yes, I could sing a little, and with some wheedling on their part and shrugging of shoulders on mine, I agreed to try a tune.

I don’t know what song it was (likely something from the Jerry Garcia songbook), but the feeling of it, boosted by a mandolin, banjo, and pair of guitars, was exhilarating. When the final notes were struck, everyone but me leaned over, grabbed an empty soda bottle off the floor, and emptied their mouths of snuff-spit. Taken as a whole, this was the best thing I’d ever experienced.

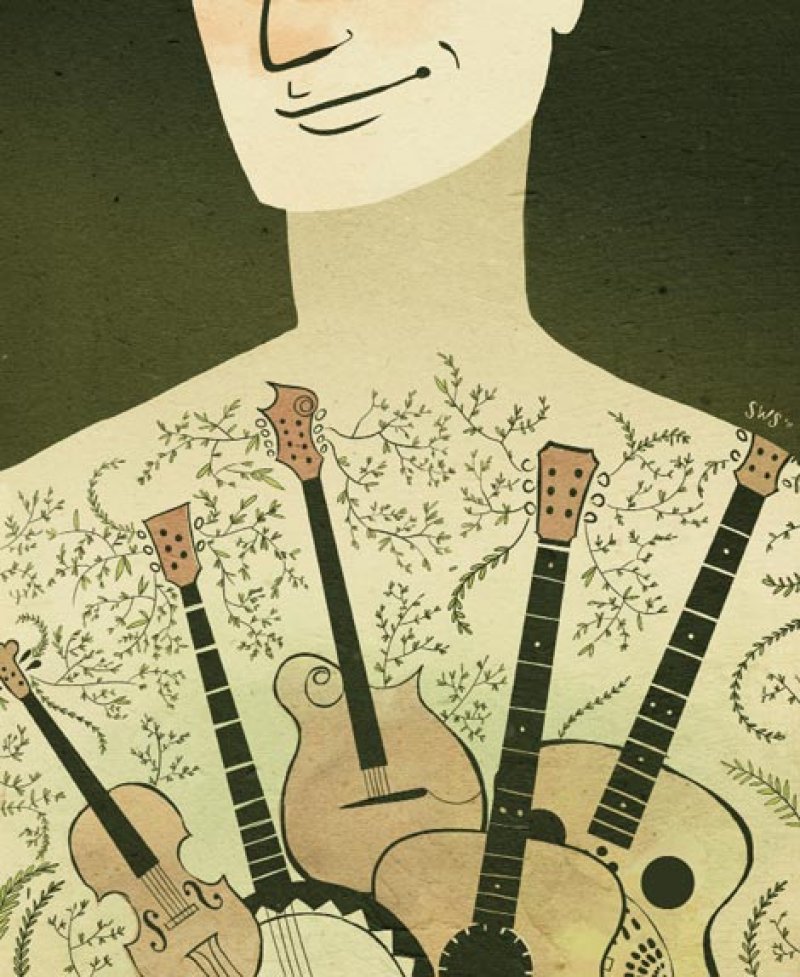

For those of us who are prone to it—who have the right receptor sites for it—bluegrass is an irresistible force. Get close enough to it, and the landscape of the mind is taken over by curls of wood-smoke and dark hollows and lonesome pines and the longest trains you ever saw. And when it’s balmy out and the dogwoods are pushing white blooms and the tallest mountains east of the Rockies are looming grayly in the twilit distance, and you happen to be from, say, Delaware, the effect can be devastating.

Of course, I was only the most recent outsider to be transformed by the music of the North Carolina mountains. Cecil Sharp comes to mind—that English scholar who popped up in the coves of Madison County around the time of the first World War, collected songs like “Sir Lionel,” “The Silk Merchant’s Daughter,” and “Rain and Snow,” and held them up to his own country’s ballads of castles and swords and fated lovers to discover something eerily familiar.

A half-century later, the mountains were set upon by a new wave of seekers, Northern city-dwellers with wispy beards and reel-to-reel tape recorders in search of genuine sounds. They’re coming here still, listeners and players from other parts of the world: buskers on the streets of Asheville; summer students at Mars Hill and Swannanoa working out ageless bowing patterns on Chinese fiddles; the sunburned throngs at MerleFest each April hearing “Nine Pound Hammer” for the thousandth time and loving it as much as they did the first.

There’s good reason for their enthusiasm. Consider just a short list of the region’s native string-music talent, both living and historic: Josh Goforth, Ralph Lewis, Arvil Freeman, Earl Scruggs, Doc Watson, Sheila Kay Adams, Trevor and Travis Stuart, George Shuffler, Don Reno, Bascom Lamar Lunsford, Etta Baker, the Blue Sky Boys, Marcus Martin, Manco Sneed, Gaither Carlton, Frank Proffitt, Mary Jane Queen. There are scores more, on and off the record, all worthy of a listen.

I’m sad to admit that bluegrass music seldom affects me the way it did back then. I’m no longer 21, no longer free to be held by a single passion, to spend my days trying to master the Lester Flatt “G” run or learn the words to “Rank Strangers.”

Just as likely, it has something to do with the setting. There are no log cabins where I live now, no rough and rocky roads, no lonesome pines. There probably never have been. But it’s fine, really. I carry that music, that feeling and the place that made it possible around with me like a small treasure, tucked just out of sight. I suspect that I always will.

Kent Priestley lived and worked in Asheville between 2005 and 2009. A longtime WNC magazine contributor and former Mountain Xpress editor, he resides in Wilmington, Delaware.