Crafted for Community: Looking back at the 100-year legacy of John C. Campbell Folk School

Crafted for Community: Looking back at the 100-year legacy of John C. Campbell Folk School: A storied history of handmade goods and mountain skills

For hundreds of years, the residents of the Appalachian Mountains have relied on their own handiness and hardiness to secure their livelihood. While establishing their own culture and traditions, our rural communities worked hard to survive in the mountains with limited resources. Before the rural development of Western North Carolina, educational opportunities were very limited, and as a result, many lived in poverty.

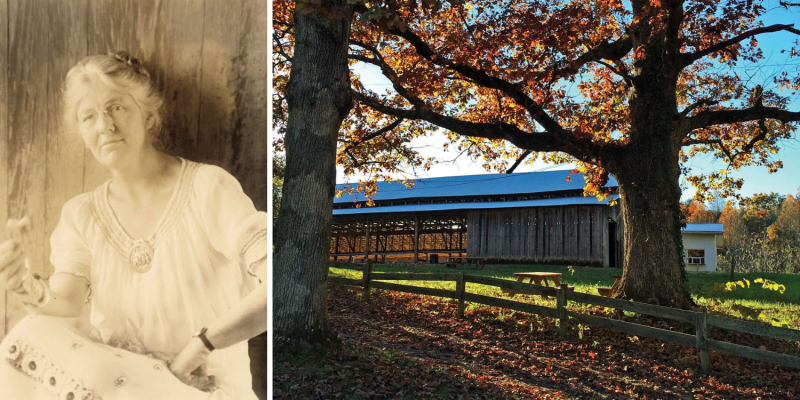

The John C. Campbell Folk School, celebrating its 100th anniversary this autumn, was founded in order to improve the everyday lives of rural Western North Carolinians. Although named after a man, the school was pioneered and operated by two women who were dedicated to providing more economic and social opportunities for our mountain residents.

Over the years, visitors and locals made the pilgrimage to Brasstown to take courses on many subjects including agriculture, woodcarving, photography and writing, leatherwork, chair caning, calligraphy, dancing and music, weaving, and basketry, among others. Offering week-long and weekend programs, as well as online classes, work study programs, and youth programs, the John C. Campbell Folk School has been an instrumental part of the community since its inception 100 years ago.

BACK IN TIME

In the early 1900s, Olive Dame Campbell and her husband John moved to rural Appalachia together to begin collecting sociological data on the local residents. John had received a grant from the Russel Sage Foundation to study the area and make recommendations for ways they could improve the educational opportunities for Southern Appalachian residents, so he and Olive spent years traveling from Georgia to West Virginia analyzing the needs of the residents by engaging with them and studying Appalachian culture.

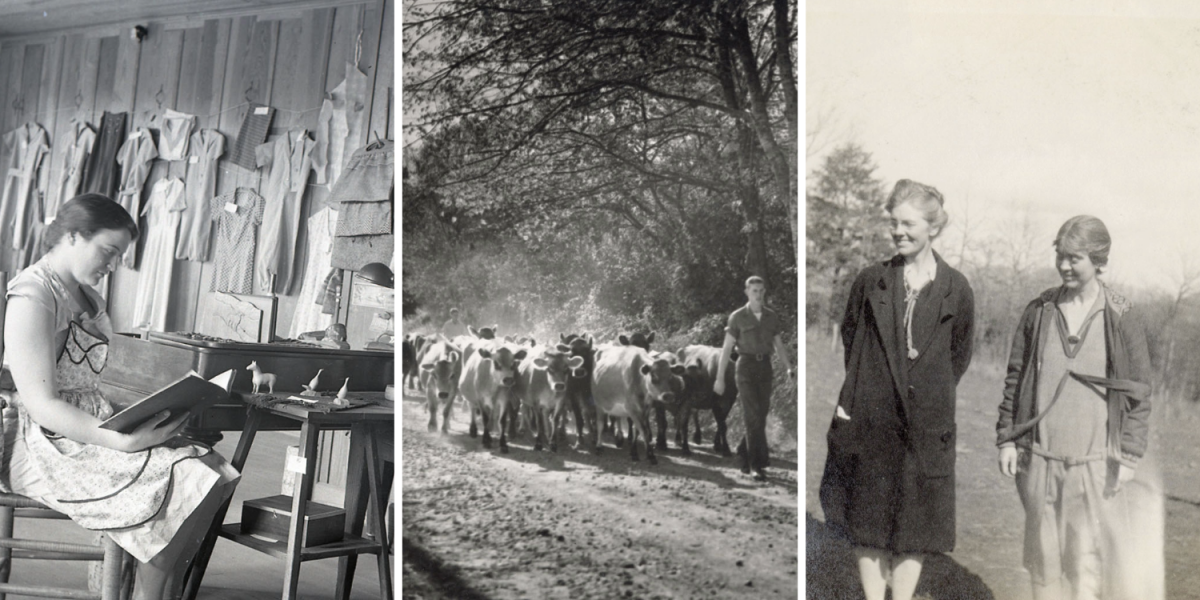

Campbell and Butler (right) worked to create programs that provided vital life skills, such as making crafts (left). Instructors like Murriel Martin helped lead a weaving class. Students even raised dairy goats, like the ones headed to town (middle).

At the time, there weren’t many options for education, and most were underfunded or church-focused; people who were seeking an education often had to travel quite a distance to attend, and these “settlement schools” often operated seasonally, not year-round. After completing their research, the Campbells concluded that educational opportunities needed to be structured differently than in other parts of the country—they needed to be hands-on and practical, not bookish and theology-based.

John passed away in 1919, before the school came to fruition, leaving Olive behind to continue their work. She partnered with Marguerite Butler, another local humanitarian and graduate of Vassar College whom she had met at a conference. Together, they examined the folk school model of education, which was becoming popular in Europe at the time.

The folk school concept was originally conceived by a theologian in Denmark who, “...offered an idea that schools should be for the people: the folk. Everything that is learned at a folk school should be relevant to the community or to the learner,” explains Folk School Executive Director Bethany Chaney. “Having conversation, not lectures and tests, but really being in community while learning was the best way to enlighten and enliven the world, to enlighten people, enliven their existence, and encourage learning in a way that we might now call lifelong learning.”

In other words, “learning by doing” seemed like it would be the biggest help to the people of Appalachia. A collaborative effort between the Appalachian people of Western North Carolina and the folk school founders began with this philosophy in mind. During a town meeting about their proposal, over 200 people showed up in a demonstration of their support for the school. Land, labor, and supplies were donated by locals looking to support its development.

WHAT THEY LEARNED

When the school finally opened its doors in 1925, farming was at the core curriculum.

Students learned about animal husbandry and dairy farming, and also grew crops like sorghum, corn, and other vegetables. Along with agriculture, the school taught woodworking (and later formed the Brasstown Carvers, a group still operating today) and other subjects that could be monetized as an extra source of income.

“The whole community was involved,” says Chaney. “It wasn’t just young people. It was older folks too that worked as mentors and as teachers, or just keeping the school running—or actively came to learn.”

The school also operated as a social hub for the community. It was a place where people could get together to converse, share knowledge, and explore their traditions. Folk music and dance was (and still is) culturally sigificant to the people of Appalachia.

“Back in 1925, there was a lot of fear about music and dance. You couldn’t have either one in church really, unless it was old-time hymns with no accompaniment from an instrument, so this was a place where people could explore music and dance. While there was resistance at first from some of the more religious folks in town, it became something that, through our ten decades, has been an absolutely important desire embraced by the community,” Chaney says.

Butler was listed in The Asheville Citizen as a folk dance caller, meaning she provided instructions to the group dances at the school. Danish native and future folk school director Georg Bidstrup also taught folk dancing classes there beginning in 1926.

Overall, the Folk School’s lessons were just as cultural as they were practical—although there were no grades, the students were still higly motivated to engage with the subjects they were learning about. Studying there was a way for people in rural areas to gather socially while also getting hands-on experience that would help them thrive in an isolated area.

LOOKING AHEAD

As the school evolved, so did the educational model. Initially, classes lasted for months at a time and students would live at the school to study their chosen subjects. But as transportation methods improved and mountain residents were able to access resources more easily, the needs of the community changed—so the Folk School did too.

“In the ’50s and early ’60s, the Folk School really struggled. There were times when there were questions about whether it was sustainable at all; even as late as the late ’60s and to the ’70s, there were sometimes hardly anybody on campus because the folk school hadn’t figured out how to pivot yet,” Chaney explains.

However, board members and directors at the time recognized that what made the John C. Campbell Folk School so enduring was its focus on Appalachian craft. “People liked the idea of sort of getting back to the way things used to be done, so that became the almost-exclusive focus slowly from the 1950s, but really came into its full—and what I’d say is the current model—in the ’80s and that is shorter courses,” says Chaney. As opposed to instruction on necessary life skills for rural mountain residents, the current course catalogue places a greater emphasis on Appalachian craft, music and dance, nature studies, and other traditional skills that are more digestible to a visiting population.

Today’s students at the John C. Campbell Folk School have access to week-long and weekend classes taught by knowledgeable experts. In 2022, the school also opened Olive’s Porch, an extension office in Murphy that offers single-day workshops on creating niche items like handmade pasta, salves and creams, and quilts.

In celebration of their 100th anniversary, the Folk School is hosting their annual Fall Festival on October 4 and 5, as well as Forge After Dark, a family-friendly hammer-in event in the blacksmithing studio on November 7 and 8. The school is also reopening the Log Cabin Museum this fall, which was originally built in 1926 and has been recently renovated and staged.

LEARN MORE

John C. Campbell Folk School

1 Folk School Rd., Brasstown

(828) 837-2775; folkschool.org