Earth's Abundance: The story of Appalachian pottery continues to evolve

Earth's Abundance: The story of Appalachian pottery continues to evolve:

In the Appalachian region of Western North Carolina, the land holds a particular kind of soil—more than just dirt. This ground is rich with clay, a natural resource created from the wearing down of rocks by heat, weather and time. When we imagine clay in our mind’s eye, it typically has no shape: a moldable lump in colors such as red, white, gray, or beige. But the magic of pottery-making transforms clay into a very human, very Appalachian art form.

The folk art practice of crafting pottery from natural clay can be traced back for centuries. Early Native American settlers of the Woodland period—lasting roughly from 1000 B.C. to 1000 A.D.—made pottery, and archeologists have discovered the remnants in North Carolina. The word “pottery” depicts the fashioning of objects from clay, then hardening the objects with fire. For these early settlers, firing was done outdoors on a hearth, a method known now as pit firing. Molded clay was first dried in the sun, usually for days, then baked upon a stone hearth.

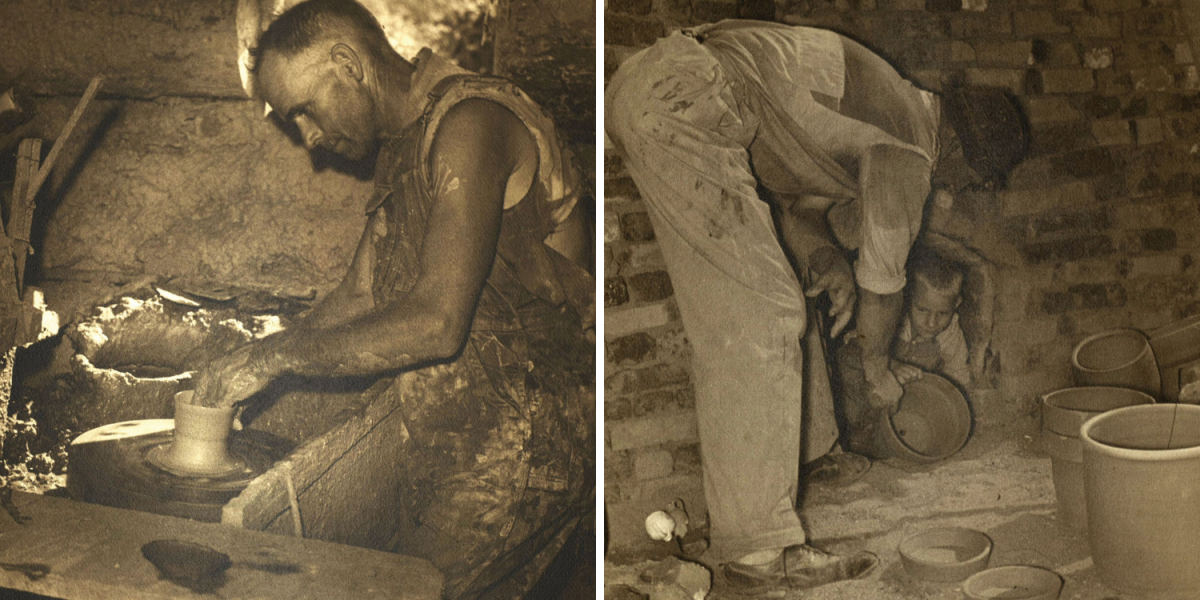

Although the tools were more rudimentary, potters of the past relied on the same tools—wheels (left) and kilns (right)—when making pottery.

The natural resources of North Carolina, including deposits of clay and plenty of wood for firing, helped pottery-making flourish. Furthermore, Appalachians have a long-standing tradition of crafting useful objects, a response to the “do-it-yourself” mentality born of its rural roots—if you can’t easily drive to a store for something or don’t have the money, you may as well fashion it yourself with what’s on hand.

Even now, in our era of rampant consumerism, the tradition of making and using pottery continues. While different areas and different artists explore new and old methods in pottery-making, the sentiment is the same: to make use of Earth’s abundance.

Ancestral Honor In Cherokee Pottery

Multimedia artist Tara McCoy lives on the 57,000-acre Qualla Boundary, land held in trust by the federal government for the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians. McCoy grew up immersed in her culture, attending Cherokee schools and “guided by local Native teachers and teaching assistants who reminded [students] of who [they] were.” McCoy’s personal history with pottery is a storied one; her great-grandmother Ella Arch, her aunt Cora Wahneetah, and her cousin Melissa Maney made pottery as a means of supporting their families during what McCoy referred to as “the tourism boom.”

As a child, McCoy was close to her grandmother, who didn’t have a car or, for a long time, even a TV. Through living simply, McCoy’s grandmother fostered her granddaughter’s love of the land and inner confidence. “I was outside constantly, either in the woods or playing in the river. That’s where I gained my deep respect for wildlife, the elements, water, and weather,” McCoy says.

McCoy retails with Qualla Arts and Crafts Mutual, a co-op that gives artists a place to sell their work and tourists a place to buy authentic, local art. Although she’s been a “proud member” of the co-op since 2001—along with her son Toby, who is also a potter—McCoy admits the art form wasn’t her first choice. Over time, however, her feelings changed.

The history of pottery in the Cherokee region of North Carolina goes back thousands of years and is deeply ingrained into the tribe. Methods in the Cherokee pottery tradition include coiling—the process of taking long, rope-like strands of clay and stacking them on top of one another—and pinching the clay at the sides to form walls, then flattening the base. Paddle stamping, a decorative technique, involves marking a still-wet clay figure with a wooden paddle.

Historically, Cherokee potters used a white, fine-grained clay known as kaolin, which is prevalent in Southern Appalachia. To create a hardier mixture, kaolin was often combined with rocks, charcoal or even seashells.

Friendship Vase (right) by Tara McCoy

Those who know their Cherokee pottery will recognize the Bigmeat name, a family tree consisting of master potter Charlotte Welch Bigmeat, who passed the art form onto her three daughters and numerous other descendants—including Joel Queen, whom McCoy has worked with.

“I’ve studied with many incredible artists, and each one has shaped my understanding and inspired my path,” McCoy adds, offering names such as the late Amanda Swimmer, Alyne Stamper, Barbara Duncan, Tammy Beane, Jan Osti, Matt Anderson, and Jared Tso to the roster of talented potters she has worked with in some capacity.

McCoy’s foray into pottery, beyond what was required in her art classes, was to make consumer-friendly objects that could garner income. A single mother at the time, she found herself turning out “fast” pieces that would turn a profit—one $11 bag of commercial clay could become $1,000 in income. Today, she prefers to slow down and savor the process of pottery-making.

“I teach community classes, study the history of Cherokee pottery, and explore my genealogy—that’s when I truly fell in love with the art,” she says. “Pottery became more than functional; it became a direct link to my ancestors. When I work with clay now, time disappears. I can go 12 hours without thinking about food or anything else, just focusing on what the clay wants to become.” McCoy’s work can be purchased at Qualla Arts & Crafts Mutual. quallaartsandcrafts.org

The Art Of Community In Catawba Valley Pottery

(Bottom-left), the Reinhardt-Craig house still stands in the Catawba region, near Vale. (Right) Michael Gates, artist & potter.

Painter and sculptor Michael Gates lives just outside of Asheville, but you can often catch him tending the land at his family’s old farm near Hickory along with his brother and father—the descendants of Enoch Reinhardt, Gates’ paternal great-grandfather, whose name is well-known in the tradition of Catawba Valley pottery. Though his great-grandfather passed away around the time he was born, Gates spent ample time with his grandparents, learning about his lineage in the art of pottery.

Referring to the area around the river near Hickory and Lincolnton, Catawba Valley potters worked by the hundreds on functional tools they could use in farm work and share with or give to neighbors. The south fork of the Catawba River offered a sizable clay deposit where they could procure their own material.

“They made stuff to use [such as] butter churns, storage crocks, pitchers, milking crocks for the cows and other farm items,” Gates says. “Enoch also cut hair as a barber in addition to farming and pottery. They did a little of everything.”

The land consisted of a groundhog kiln—a special wood firing kiln buried inside the ground, hence its name—as well as a shop. Known now as the Reinhardt-Craig House, Enoch and his younger brother, Harvey, sold the business to their neighbor, Burlon Craig. At the dawn of the Industrial Revolution, functional pottery gave way to tourism-based pottery—but certain artists, including Craig’s protegés, Charlie Lisk and Kim Ellington, continued much of the original tradition, with Ellington still actively making art and Lisk retiring “as a legend,” in the words of Gates.

While Gates found himself drawn to the arts as a kid, he never considered pottery and instead leaned toward drawing and painting. He thought it was “cool” that his family members had been potters, he says, but initially thought pottery was a thing of the past—then he signed up for a ceramics class as a fine arts student at UNC Greensboro. “That was the turning point,” he says. “That’s when I realized pottery is very much alive.”

Gates decided to concentrate on clay art for his senior project, but, after college, he returned pottery to the back burner. For a handful of years, he traveled around the United States, painting and presenting in various shows. Then, after a stint in Southern California, he decided to move back to the East Coast. Settled in Charlotte, he continued to paint and slowly began making pottery again. Now, he’s a potter full-time, mostly working in a home studio and firing at various locations with other potters in the community.

“I’ve been working with Matt Jones, firing with him and a few other people the last few years—both new and established potters,” he says. “It’s an interesting group. One guy, Preston Tolbert, teaches pottery at Catawba Valley Community College, and it’s nice to see younger people getting into it and see them excited.”

The Catawba Valley pottery tradition takes a page from Black indigenous potters, who would often decorate jugs and other vessels with faces. The practice caught on and passed through various family trees. Another method, swirl ware, entails combining multiple colors during the pottery throwing process, resulting in custom patterns.

“Everyone had their own spin on the faces,” Gates says. “The ones my great-grandfather made all kind of looked the same, and he made more pitchers than jugs. His brother, Harvey, also made them, and both their styles got me making face jugs.”

Though he emulates some of the traditions from the past, Gates says he doesn’t have a particular creative process and likes to keep things “open-ended” as far as what the clay will become next. Most recently, he’s edged away from functional objects, crafting decorative sculptures such as his new series of luminaries, which can hold a candle or incense. He sells his work through a handful of galleries in the area, as well as at the Catawba Valley Pottery Festival every year in Hickory. A spring and summer art show titled “I AM” at the Hickory Museum of Art—closed on August 31—displayed fine art pottery by Gates.

As for his family’s land at the Reinhardt-Craig House, Gates has cautiously high hopes. “I don’t plan to live there full-time, but we definitely want to have it part-time and get the kiln working,” he says. “I want to keep it in the family and have a place to work and have firings with friends. But the kiln hasn’t been fired in almost 100 years—so it would be a big deal if it was fired!” See more of his work at michael-gates-pottery.square.site

Magical Connections In Asheville-Buncombe Pottery

Michael Hofman uses delicate lace fabrics (bottom-left) to produce detailed patterns on a variety of pottery pieces, including plates (bottom-right), jugs, and pitchers. The lace is skillfully arranged and pressed into the raw clay to create a precise impression (top-right).

Michael Hofman was a self-declared “fabric-aholic” before he became a potter in Asheville. The Indiana native attended Notre Dame, where he obtained a degree in industrial design, then earned a master’s in fine art from Ohio State before moving to San Francisco. But even 20 years ago, the Bay Area was expensive enough that Hofman dabbled in different gigs to make ends meet, including making pillows, curtains and other goods, as well as working in galleries.

When he moved to Asheville, sight unseen and with faith in the wonderful things he’d heard about the area, Hofman realized it would be difficult to get another job in a gallery; they were all owner operated. But soon enough, he discovered a pottery studio with owners who wanted to sell. That was 21 years ago. Today, Hofman Studios is thriving.

Hofman focuses his art on a particular kind of pottery made with porcelain. Because it can handle higher temperatures, objects made with porcelain—typically a combination of kaolin, grolleg and other materials, including bone ash—are more delicate but are less prone to breaking. The process for making objects from porcelain is the same as any other pottery: The potter molds the clay, dries it, fires it and glazes it.

For Hofman, getting creative with the glaze is part of the fun of porcelain. “I set pieces out overnight and dip them in a different glaze,” he says. “You can get some wonderful effects from the two different glazes.” Another tradition he’s resurrected is one that he learned from older potters in the area: using lace fabric to imprint patterns, a satisfying nod to his love for textiles. Both glazing and lace-imprinting are easier with porcelain.

“I couldn’t make what I’m doing with anything but porcelain; any other clay would break in my hands,” Hofman says. “You can use lace on regular clay, but you wouldn’t get as detailed an imprint—porcelain has finer particles. Also, porcelain is white, so it has a great effect on the glazes.”

Buncombe County is one of a only a few areas in the state known as a “jugtown,” an attestation of the local craft history and traditions that influence Hofman. The region has attracted many potters over the years since the land is enriched with raw clay formed by nearby waterways.

In the mid 1700s, the Penland family purchased 25 acres of land on Hominy Creek in Candler, and in 1844, their descendants began producing pottery with a South Carolina transplant named EW Stone. Over the years, the families remained close, and continued to operate what became known as Jugtown Pottery before the studio eventually closed in 1945.

Toward the end of Jugtown Pottery’s run in Candler, Trull Pottery opened its doors just down the street. Both Trull and Penland-Stone were family operations, selling alkaline-glazed utilitarian pottery like tableware and horticultural tools to their community.

In 1924, potter Davis Brown arrived in North Carolina, bringing sculpting knowledge from his native Georgia to the Arden area. He and his brothers—Javan, Willie, and Rufus—formed Brown Brothers Pottery, which, like their predecessors, produced items that served a purpose, almost exclusively covered in a signature dark brown glaze.

Like their upstate counterparts, the Browns also created face jugs. Their whimsical, evocative expressions make Brown’s Pottery faces popular among collectors. Up until a few years ago, Davis’s descendant Charlie was still producing eccentric face jugs for the family store in Arden.

However, the modern pottery community in Asheville and Buncombe County, according to Hofman, tends to be more experimental. In the River Arts District, a number of potters work with porcelain, but, no matter the medium, artists are glad to meet each other. “Asheville is a magical place, and things happen here—you meet people who become important in your life,” he says. “In a serendipitous way, you end up connecting with people here.”

That sense of artistic community is one reason the area thrives even after the challenges of Hurricane Helene. Though Hofman speculated about 80 percent of the River Arts District was wiped out, those who were not are able to help those who lost everything. One supplier of clay and pottery tools in the area, Highwater Clays, was forced to close due the flooding, but The Odyssey School of Asheville, a nonprofit, arts-forward institution, has purchased supplies for area potters. Hofman himself is currently hosting fellow potters in his retail studio. And this October, The Village Potters Clay Center will reopen one year after the flood, further strengthening the Asheville-Buncombe community.

“I moved my production to my home studio, which is where I make everything now, and the space at the River Arts District is all retail, which is how I brought in a few other people,” Hofman says. “Anyone who has the space has opened it up to others. And from that came even more wonderful connections.” See more of his work at livelifeartfully.com