The Backcountry Beckons

The Backcountry Beckons: Western North Carolina’s many hiking trails and campsites offer a serene respite from urban life. But for a more daring adventure along the trails less traveled, consider staking out in our wild frontier.

True backcountry beckons in our western mountains. The stellar assortment of primitive land parcels range from federally designated wilderness areas, such as Linville Gorge and Shining Rock, to large trail-laced tracts in the Pisgah and Nantahala National Forests and the Blue Ridge Parkway, and within countless square miles of Great Smoky Mountains National Park.

All offer multi-mile treks between primitive campsites that immerse the explorer in silence, if not total solitude. The rewards and challenges of such wanderings are widely known and romanticized, in part because backcountry travel often dishes out challenge and reward at the same time. Straining climbs and stiff descents, the need to feed and shelter yourself, and encounters with wildlife are just a few of the hurdles.

That’s why most folks still stick to the “frontcountry,” places in our parks and forests with formalized campgrounds, picnic areas, visitor centers, nature trails, camp stores, and snack bars. Luckily, the Southern Appalachians still retain backcountry long after it disappeared elsewhere in the country.

Actual virgin forest—truly old-growth wildlands—are largely gone. Mother Nature lost that battle to apocalyptically destructive logging in the early 20th century, but she won the war in 1911 when passage of the Weeks Act created national forests in the East. Great Smoky Mountains National Park amplified that acreage in 1934; the Parkway helped in 1935, and state parks have, too. After a century of healing, the Southern Appalachian backcountry is back, encircling us with vast public lands that enrich our lives and lifestyles, and even drive our economy.

Black Balsam Knob, a wide-open space perfect for camping.

HOW WE GOT TODAY’S BACKCOUNTRY SCENE

Backcountry camping has deep roots in Western North Carolina. The sport has morphed over decades, and the list of necessary gear and skills has evolved since early explorers trudged up trails with unbearable burdens.

Western North Carolina chronicler Horace Kephart (1862-1931) was of that early ilk. He came to WNC in the early 1900s as a librarian intent on abandoning his career (after his family abandoned him) and set out to live a pioneering Great Smoky Mountains lifestyle when the virgin forests still reigned. He and his friends, including Japanese photographer George Masa, ended up helping turn the Smokies into a national park (each has a Smokies summit named after him).

Kephart’s classic book Our Southern Highlanders, extolls mountain culture, but his most significant period piece as an early camper was the 1906 Camping and Woodcraft. Kephart made his living in the early 20th century men’s outdoor magazine market writing for Field & Stream. The book documents a time when every camper swung an axe building the rustic, but destructive infrastructure needed for comfort in the wild. The most enduring of these conveniences are the “facilities” that modern campgrounds still provide today—fire pits, grills, picnic tables.

The Boy Scouts, born as Kephart was arriving in the Smokies, carried his “camp craft” legacy onward. In 1938 the now-legendary Philmont Scout Ranch in New Mexico was created and is famed for its lengthy backpacking trips, still enjoyed today by Boy and Girl Scouts. WNC’s rich summer camp culture arose during this time. Log cabin barracks, enrichment programs . . . that local heritage still endures.

Something changed in the late 1960s. Modern, light-weight camping gear gained widespread appreciation on the back of author Colin Fletcher, the “father of modern backpacking.” Fletcher’s books, including The Complete Walker “gave meaning to backpacking,” says Buck Tilton, an early editor of Backpacker magazine. The book even pitched the best gear to buy.

The race to the woods was, in part, led by long-haired hikers intent on privacy for pursuits not strictly related to nature appreciation. Among them were folks who’d once suffered the hardship of hauling a Boy Scout “Yucca pack,” a canvas rectangle devoid of both pockets and padded straps. When ergonomic, feather-weight, frame packs with padded straps emerged, it was a no-brainer to embrace them. “Suck it up” was no longer the mantra.

Today the impetus for “taking a walk in the woods,” albeit overnight, is more complex and goes way beyond importing the baby boomer’s counterculture into the backcountry. Backpacking today is more about communing with nature, and includes seeing our green world as an antidote for “nature deficit disorder,” especially among kids, some more used to staring at screens than taking in a summit view. Some backcountry campers, especially the long distance variety, are endurance athletes setting records for “taking a run in the woods.”

Doughton Park (above) is the largest recreational area on the Blue Ridge Parkway.

A NEW WORLD

That story of renewal was so successful that many took it for granted—or did until now. Then Tropical Storm Helene paid us a visit on September 27, 2024. That event came closer to destroying decades of recovery than even the worst historic hurricanes back in 1916 and 1940.

Helene challenged land managers—and all of us—to take the long view. The beauty we had will return, especially with droves of local volunteers clearing trails alongside understaffed (and sadly, even underappreciated) public park and forest employees. Luckily, backcountry will still be accessible in less impacted places or where park pros and the public have cleared the destruction.

That said, some might argue that now is just not a good time to take a backcountry camping trip. Helene’s remaining dangers of falling trees and still-sliding land will take decades to mitigate. Realistically though, WNC is such a nationally-known hotspot for backcountry recreation that it’s unlikely adventurers will stay away. The earliest started making their way north last spring on the Appalachian Trail.

That means now is the perfect time to tell both expert and inexperienced backcountry hikers and campers that the post-Helene environment poses unique dangers.

BIGGER THAN YOU THINK

By now, anyone who frequents North Carolina national forests, parts of the Blue Ridge Parkway, state parks like South Mountains, or the Great Smokies has heard dire reports of epic destruction—along with, at times, confusing trail and park closure announcements. You’ve also likely heard people griping about it, too. “Well, there’s no damage on the Parkway where I am, why is that section of road still gated, or that trail still closed?”

The bottom line, as shocking as it sounds, is that Helene is the largest, most devastating natural disaster to ever hit any national park, an assessment shared by many park and forest professionals. On and off the Parkway, repairs and closures may take years.

After I dug out, I was shocked passing the Profile Trail on the flank of Grandfather Mountain to see forests flattened like someone dumped a pile of toothpicks on nature. That and other damage have closed the trail for the foreseeable future; similar scenes dot the landscape all over WNC. Add to that thousands of landslides, massively altered creeks and streams, and the loss of bridges and roads, the damage boggles the mind and reflects why the task of assessing damage is so big that it’s likely impossible to have definitive information.

In truth, some damage isn’t even visible. It’s likely that every wind or rain storm for years will yield day-to-day changes in what hikers and foresters face. Clearing that kind of damage is fraught with complicating factors. “A hiker might be used to looking both ways in all kinds of situations,” one forest service trail maintainer told me, “but the people struggling to clear trails and facilities aren’t necessarily looking for hikers.”

Thus, it is more essential than ever to know and comply with all permit requirements in places where you’ll be camping. Add to that the need-to-know, and make sure you obey trail alerts and closures, which are now routinely found on the websites of forests and parks.

Most people use designated or existing campsites (the former are mandatory in the Smokies and most state parks, the latter recommended at many places to reduce damage). But there are “bushwhacking” explorers who avoid trails and previous campsites. There are also federal wilderness areas where trails are largely unmarked and difficult to find in the best of circumstances (think Linville Gorge and Shining Rock). Especially post-Helene, the trail-less explorer may have some serious thinking to do about where to go, what to bring, and how to behave in unexpected circumstances.

Shining Rock Wilderness was one of the first areas to become part of the federal Wilderness System in 1964. It’s also the largest of its kind in the state.

USE COMMON SENSE

It’s safe to say both hikers and campers should take added precautions for the unexpected this summer and fall. Campers are the best equipped. They plan to camp, but a word to the wise for day-hikers: be sure your list of essentials (page 105) truly permits you to “be prepared.”

That’s especially true, says former North Carolina Outward Bound instructor and NC State University professor Aram Attarian, “if a long day turns into an overnight, whether for yourself or someone you encounter.”

Having what you need with you is particularly important now, “because if you or another party need to be rescued, it’s going to take longer than normal with damaged trails and higher demands on responders,” Attarian says. “Sadly, with so many cuts in forest and park agencies, who knows what resources may be available.”

Attarian is assistant task force leader for section four of the Mountains-to-Sea Trail (from Mount Mitchell, past the Linville Gorge, to Beacon Heights on Grandfather Mountain). “Perhaps most important,” he says with a twinge of sarcasm, “use common sense . . . if you have any.”

Attarian has seen it all, and his lamentable conclusion is “many people just aren’t prepared. That suggests being sure someone knows your travel plans—and stick to that plan,” he says.

“No shortcuts or surprises—and that means stay away from landslides, and off of, and out of, wind-flattened forest areas. Damage from Helene poses extreme dangers. In the wrong location, falling forward or backward and breaking a leg or ankle among tree trunks could have tragic results.”

Actually, Attarian suggests, “build more time into your plans, not less. Don’t get in a hurry.” After all, having time to chill and smell the flowers is exactly the respite many seek in the backcountry.

Other hidden hazards? Be “terrain aware,” Attarian warns. Recently a fly fisherman had to be rescued from Wilson Creek when he got stuck in quicksand that was not there before Helene. “The rivers have changed,” he says. Also, “be ‘tree’ aware.” Summer leaves will hide hurricane damaged limbs, or weigh them down. Wind will turn branches into sails. “Put real thought and analysis into where to pitch your tent.”

Grab Your Gear

Some say backcountry enthusiasts love the gadgets and gear as much as nature. That’s because the yin and yang of backcountry camping is balancing the tension between the urge to splurge (on weight) and the need to find the lightest gear to ease the aches and pains of packing. Mast General Store outdoor buyer Chris Collins weighs in. >>READ MORE

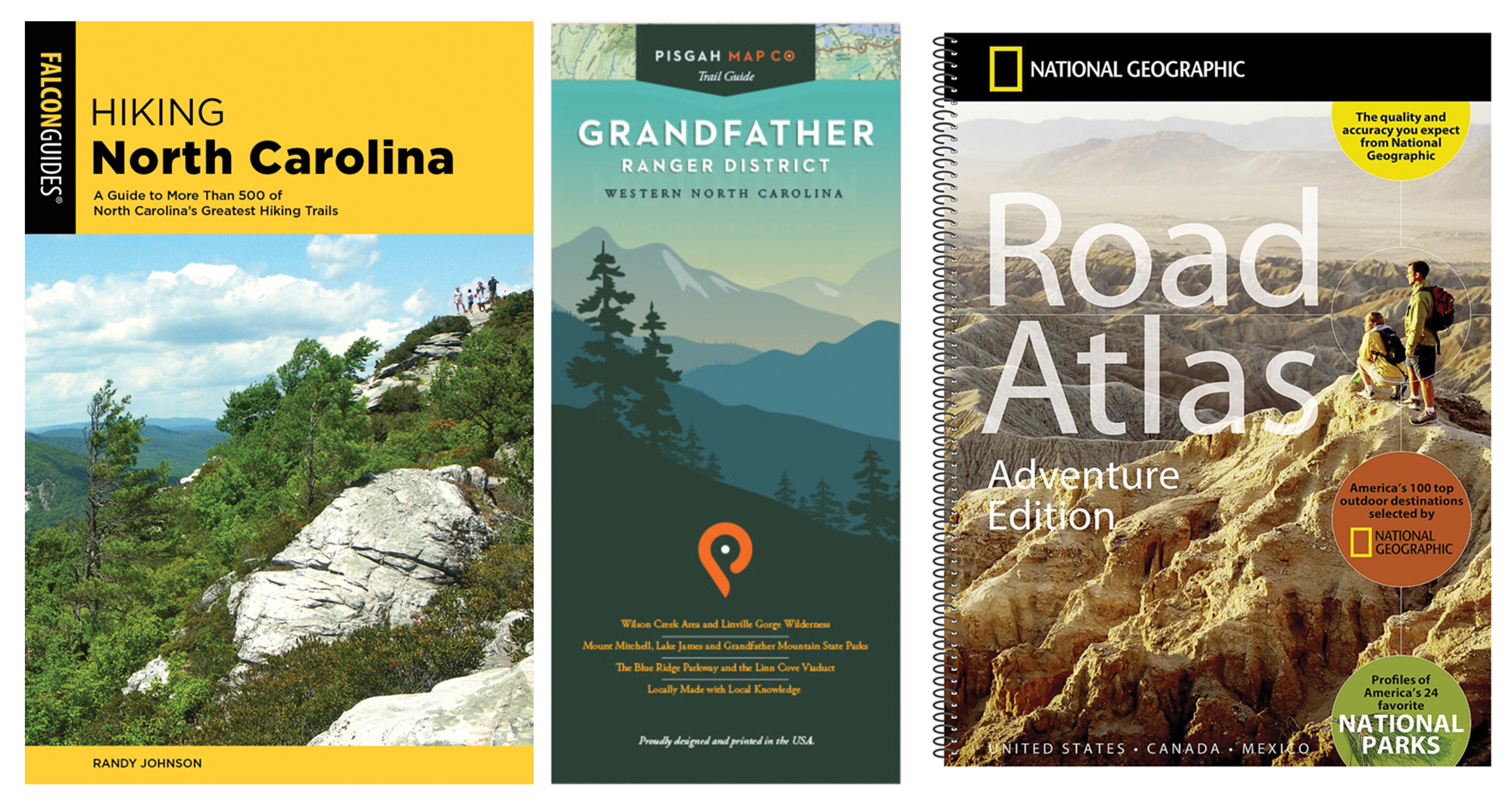

Books for the Backcountry

The classic WNC trail shops Footsloggers have been sending people into the woods since 1971. Brian Baldwin, manager of the Blowing Rock store has his finger on the pulse of what to put in your pack. >>READ MORE

(Left to right) Panthertown Valley, Schoolhouse Falls; South Mountains State Park.

Destinations

A lot is up in the air with this summer’s backcountry camping scene. Helene damaged many of the best backpacking areas, which are still being evaluated or prepared for opening. The list below of public parks and forests are a few of the reliable areas open for backcountry camping, though visit their websites for the latest info. >>READ MORE