School Under Scrutiny

School Under Scrutiny: The FBI’s files on Black Mountain College tell a little-known story of art, politics, and surveillance

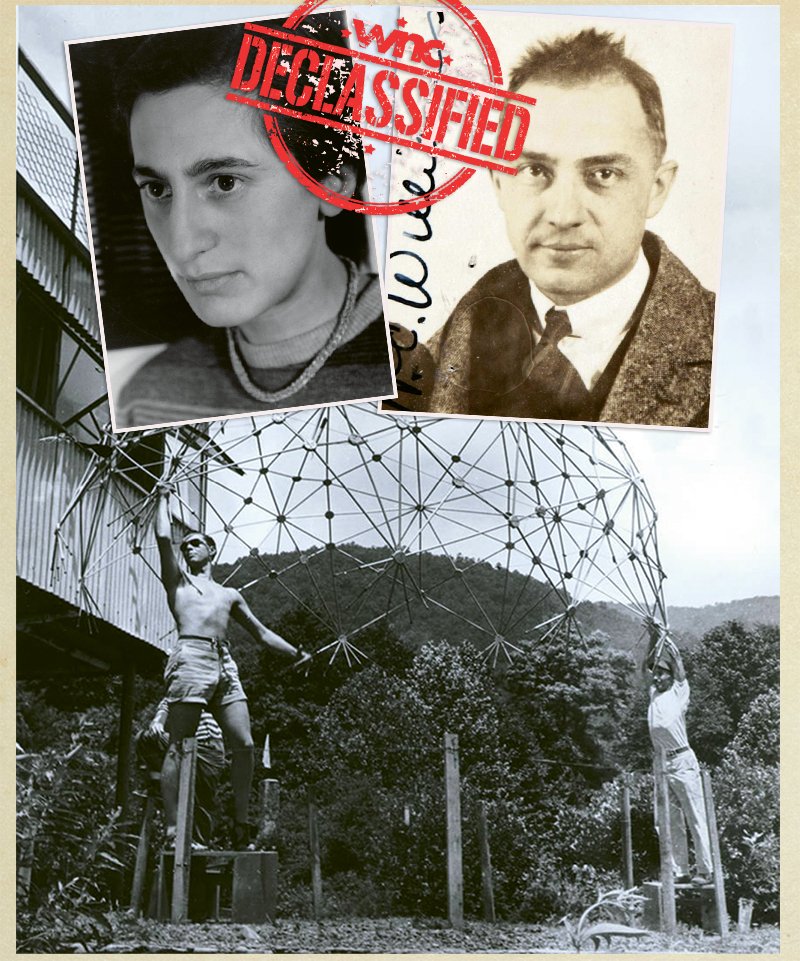

Unusual Education: Top left and right, textile artist and professor Anni Albers and poet and college adviser William Carlos Williams appear in the FBI’s secret records, as does inventor and instructor Buckminster Fuller, who designed the first geodesic dome while at Black Mountain College.

Sometimes, state security appears in unexpected places.

At Black Mountain College’s Lake Eden campus in eastern Buncombe County, “FBI people showed up all the time, and they looked like something out of a grade B movie,” the painter Dorothea Rockburne, a student in the early 1950s, later recalled. “They always had trench coats on, and you could spot them a mile away.”

The college’s run was relatively short—24 years—yet it sparked inspirations that live on to this day. An avant-garde, multidisciplinary center of artistic innovation, it stretched the concept of higher education to its limits. But while its extraordinary output is well-documented, the FBI’s watchful eye on BMC has remained largely in the shadows, only recently coming to light.

Fleeing Fascism

The college was founded in 1933 by four progressive mavericks—dissident faculty members from Rollins College in Winter Park, Florida, who lost their jobs after refusing to sign a loyalty pledge demanded by Rollins’ president. BMC started small, with just 21 students, but its reputation as a haven for new approaches to the liberal arts spread quickly. In its heyday, it was home to such luminaries as composer John Cage, choreographer Merce Cunningham, and sculptor Ruth Asawa, to name just a few.

The same year BMC opened, events in Europe helped drive the college’s trajectory: As Adolf Hitler and the Nazis took control of Germany, they shuttered the Bauhaus, a similarly innovative arts institution in Berlin, driving several faculty members into the welcoming arms of Black Mountain College. Walter Gropius, the architect who founded the Bauhaus, was among them, as were Anni and Josef Albers, a textile artist and a modernist visual artist, respectively, who became two of the college’s most renowned figures.

(Clockwise from top left) Paul Radin, professor; Albert Einstein, board of advisers; Charles Olson, rector, 1951-’56; Jonathan Williams, student.

It is a historic irony that these refugees from fascism, and many of their colleagues, came under the glare of the FBI, where Director J. Edgar Hoover enforced a wariness of cultural movements that bucked the norm. BMC was a “very unusual type of school,” the bureau noted in one of its secret reports.

According to Jay Miller, a philosophy professor at Warren Wilson College who’s long studied BMC, the college always had a complex relationship with its times. “On the one hand, the stereotype of BMC as an apolitical refuge, removed and insulated from the politics of its era, doesn’t square with the way it pitched its brand of liberal arts education as a distinctly democratic undertaking, or its embrace of political refugees, or its progressive stance on Southern racial integration,” he says. “On the other hand, BMC was certainly not the hotbed of communist activity or the colony of nudist anarchists and pacifists suggested by other stereotypes.”

Out of the Shadows

Rockburne, the painting student, recalled that sometimes, the FBI agents met their match during visits to the college. “Of course the students at Black Mountain put on an act for them. One of the favorite student tricks was to not have shoes on in the middle of winter, and crunch out a cigarette butt with their bare feet,” she added. “It confirmed their worst opinions, and we did not answer any of their questions.”

The students’ silence, however, did little to stem the FBI’s surveillance. For example, the bureau compiled an extensive dossier on the writer Charles Olson, who served as BMC’s last rector, interviewing him at least twice in the 1950s. “I have had to feel that shadow,” he wrote to a friend, comparing the FBI to “the secret police.”

Also drawing the FBI’s interest and speculation was Paul Radin, a noted cultural anthropology professor. In the mid 1940s, the bureau went so far as to recruit a secret informant who attended Radin’s classes. According to a declassified report, the informant shared allegations that Radin was “extremely radical in political and scientific views and admitted he was a member of the Communist Party,” while noting that he had “the reputation of being a brilliant and extremely capable authority” in his field.

In addition, the FBI recorded, Radin was an early and fervent advocate of civil rights. He “expressed the opinion that there was no formal difference between the white and colored races and that civilization will prosper best when racial discrimination and social inequalities … no longer exist.” By the time the FBI closed its file on the professor, it included more than 100 pages of information about Radin’s professional and private life.

If Radin’s name doesn’t ring a bell today, some of BMC’s advisers and guest lecturers who also caught the FBI’s attention might. The bureau built sizable files on several of them, from visionary inventor Buckminster Fuller to Beat poet Allen Ginsberg to yet another notable who had fled the Nazis: Albert Einstein.

Confidential No More: Declassified FBI documents about Black Mountain College include this 1945 report on anthropology professor Paul Radin and a 1956 one (beneath) on students studying under the G.I. Bill.

Free Nature

FBI agents scrutinized BMC until its waning days, according to a file declassified in 2015 under the Freedom of Information Act. The documents, dating from 1956, record the bureau’s investigation of how the college was staying afloat—in part, with nine students who were funding their education via the G.I. Bill. A Veterans Administration official had concerns that what was going on at the college might entail a threat to “internal security,” the FBI noted. (What’s more, state education authorities had long been trying to revoke BMC’s accreditation.)

By then, BMC was already on its last leg, dying of its own volition due to internal squabbles and mounting financial woes, but the McCarthy-era federal probe of the campus doubtless made things seem even gloomier. FBI agents grilled Olson about the school’s operations, then three of the students as well.

One of them was Jonathan Williams, the late photographer, publisher, and writer. The agents paid him an unexpected visit at his summer home in Highlands, North Carolina. Williams was studying “advanced verse and professional writing,” the FBI noted, and he considered his academic work to be totally above board.

“While there may appear to be some laxity in the keeping of records by the college, I do not feel that there has ever been any intent to misrepresent anything to the Veterans Administration,” Williams said, according to the FBI. “Because of the free nature of the college the student is equally responsible for maintenance of requirements, and, in my own mind, I consider that this has been done at all times.”

The other two students concurred, and the bureau noted that the VA had “furnished no specific information indicating subversive activity on the part of the students or instructors at the school.” Then, the investigation appears to have melted away, and the college closed its doors in 1957. In one of its final reports on BMC, the FBI summed up a key reason it had cast a wary eye on the college—one of the school’s core and unabashedly unconventional values.

“A student may do nothing all day and in the middle of the night may decide he wants to paint or write, which he does, and he may call on his teachers at this time for guidance,” the FBI gravely noted. “They advised that everything is left to the desires of the individual.”

POLITICS AT BLACK MOUNTAIN COLLEGE

Delve deeper with a multimedia exhibit featuring the declassified FBI documents and much more

February 1 to May 18

Black Mountain College + Arts Center

120 College St., Asheville

(828) 350-8484

blackmountaincollege.org