Legends & Lore of Western North Carolina

Legends & Lore of Western North Carolina: Standout stories from regional lore that confound and fascinate with each retelling

The sometimes-campy WNC Bigfoot Festival, a smash hit in Marion since its founding in 2018, is on hiatus this year, but local Bigfoot aficionados continue the search in earnest.

Some local legends speak of phantoms, ghosts, and other specters. Others shine light into the murky mysteries of cryptozoology—the study of mythical creatures that some consider as real as the verified species of the world. Whatever you believe—or want to believe—here are standout stories from regional lore that continue to confound and fascinate with each retelling.

Bigfoot: “You’re looking at something that don’t exist.”

One after another, the true believers stood to tell their stories of bone-chilling encounters with shaggy, shadowy giants lurking just off in the distance. “You’re trying to figure out what it is when you’re staring at it,” one man tells a crowd of hundreds gathered on the courthouse lawn in Marion. “You’re looking at something that don’t exist. And it lets out this big scream with a growl in it. It sends chills through your body.”

The McDowell County scene was a highlight of the first WNC Bigfoot Festival, an event organized in 2018 by a local group of fervent amateur investigators whose dogged determination to document the half-man, half-ape has stoked renewed regional interest in the legendary beast. The festival, which drew a reported 40,000 people last year, has been canceled due to concerns about the spread of the novel coronavirus this year, but organizers are planning an expanded event for 2021.

The event is just the latest sign of an enduring fascination with Bigfoot that spans centuries and cultures, with tales of a forest-roaming giant—sometimes called Sasquatch or Yeti—that resembles man, but who remains wild and elusive. In Western North Carolina, the creatures have also gone by names including Knobby and Boojum.

While Bigfoot in the US may be most often associated with West Coast wilderness areas (who can forget the 1967 Patterson-Gimlin film clip shot in California?), the WNC mountains have seen their share of activity, according to the Bigfoot Field Researchers Organization. The nationwide group of believers founded in 1995 documents and then tries to verify sightings. The group has counted about a dozen reports in the region, including at least five in Macon County alone.

But it’s been Bigfoot 911, a devoted group of Marion-based cryptid researchers, that has been most active recently. One of its members reported a sighting around Lake James in 2017, an episode that sparked heightened interest and then the festival.

Bigfoot 911 sponsored the first Blue Ridge Bigfoot Conference at McDowell Technical Community College this past February. It brought together top researchers who shared their experiences and knowledge. They talked about new areas of investigation that focus on how Bigfoot creatures communicate with stick structures, and whether Bigfoot may travel between dimensions to elude those who seek to find it.

Lori Wade, who focuses on sightings in Tennessee, Alabama, and Georgia, said the mountainous lands of north Georgia and WNC rank as a current hot spot for activity. And Lee Woods, who regularly presents new evidence of encounters, including casts of footprints, on the Bigfoot 911 Facebook page, remains defiant in the face of skeptics.

“We’re going to put North Carolina on the map,” he said in a July post. “We’re going to find it, and we’re going to catch it.”

A Close Encounter:

In the summer of 2017, Bigfoot 911 founder and leader John Bruner reported what he said was a significant sighting during a research mission in McDowell County. Here’s his full account (with slight spelling and punctuation adjustments), which he posted to Facebook:

“We did an expedition last night at research area # 1 and we hit pay dirt. We had 3 teams in the woods and I had deployed glow sticks at various places in the area. One of the teams had walked up to where I was stationed, we began hearing movement off to our right maybe 3 steps at a time. There was a glow stick about 30 yards from where we were, we heard a whistle [and] I looked up at the glow stick and it disappeared then came back into view. The angle of the moon was shining straight down on the road and something big stepped into view. I turned my headlamp on and I saw a large bi-pedal animal covered in hair. It took 1 step into the woods. I took off running toward where it went into the woods. I entered the woods about 50 yards and stopped to listen—I didn’t hear anything. I scanned the woods with my light. It was standing 30 yards to my right with its right hand on a tree that had been broken off 9 feet above the ground. Its face was solid black no hair on it; the hair looked shaggy all over. It turned and took 5 steps and was at the bottom of the hill, probably 30 yards. I could see the gluteus maximus flexing with each step. We tracked it as far as we could, never saw anything else. On the way out of the woods kept having rocks thrown at us. Wow what a night.”

Today, the final resting place of Leila Davidson Hansell in Oakdale Cemetery is encased in concrete, as it has been since 1937 when its opaque glass “windows” were covered.

The Sunshine Grave: A “lonely sleep in the darkness she feared so much”

Some souls push against eternal darkness more than most. Consider the curious and poignant case of Leila Davidson Hansell, a Hendersonville woman with a sunny disposition who was determined to bask in the light, even after her demise.

A Charlotte native and scion of the influential family of Davidson College fame, Hansell became a schoolteacher in Henderson County and then moved to Georgia after marrying a powerful judge. But when she took ill with tuberculosis, she returned to Hendersonville to seek healing.

It was for naught, and before her death in 1915, at 54, Hansell implored her husband to make sure that the sun would always shine on her. And so the judge commissioned a special vault in Oakdale Cemetery, one both humble and extraordinary. It bore no name or epitaph, but the three-foot-high brick structure had a singular feature: a cover inlaid with opaque glass fixtures to let in at least a modicum of Hansell’s beloved sunlight.

For the next two decades, the legend of “The Sunshine Woman” spread, and locals and visitors alike gravitated to the grave. Word was that Hansell’s very corpse could sometimes be seen through the glass panels, when the light was just right. The accounts varied as much as they multiplied. When a tree’s branches stretched over the grave, for example, some witnesses swore that Hansell’s remains turned to dodge the shadows.

The undertaker who interred Hansell called such accounts nonsense, protesting that while it was true that the dearly departed had been buried with the top half of her casket open, her remains were draped in a shroud that would have made seeing her impossible. At the same time, some observers speculated that a crack in the vault’s concrete had let in sufficient moisture and sunshine to cause the shroud’s decomposition, leaving Hansell’s skeleton exposed.

Ultimately, town officials found the hubbub, speculation, and cemetery crowds to be too much, and in 1937 they ordered that the minimalist mausoleum be sheathed in concrete. And so it sits today, much as it did when the late Henderson County journalist Frank FitzSimons took note of it in his 1950s radio broadcasts. “No longer visited by the curious,” FitzSimons reported, “the Sunshine Lady sleeps her lonely sleep in the darkness she feared so much.”

Today, the Cherokee County Historical Museum displays a three-foot-tall statue, uncovered in Murphy in 1841, that some believe depicts the Moon-eyed People.

The Moon-Eyed People: A world “clothed in secret and mystery”

From elves to fairies to leprechauns, various world cultures pass on stories of small beings of yore who still provide enduring narratives. But few such tales rival that of the Moon-eyed People, aka the Cherokee Little People, which the Cherokee called, in their native tongue, the Yuñwi Tsundí.

Cherokee oral history paints a rich tapestry of interactions with the Little People, as ethnographer James Mooney found in the late 1880s, when he lived among the tribe and wrote the seminal work Myths of the Cherokee. In it, he recounted a “dim but persistent tradition” that kept cropping up. Accounts differed on the particulars but were consistent on the basics. The Little People were said to grow only about three-feet tall. They couldn’t see in the light, perhaps accounting for their nocturnal activities and larger than normal eyes, and they lived underground or in caves. They were either light-skinned or clad in white, with their men growing flowing beards. They possessed magical knowledge and practices, and alternated between living in helpful accord with the Cherokee and finding conflict with them.

Even today, some authors point to supposed discoveries of small skeletons and the remains of subterranean domiciles to authenticate the stories of the Little People. Perhaps the most complete compendium on the subject, The Secrets and Mysteries of the Cherokee Little People, was authored in 1998 by Lynn King Lossiah, a member of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians. The stories offer a window into a world “clothed in secret and mystery,” she noted—along with lessons about living with neighbors who are both decidedly different and share your common ground.

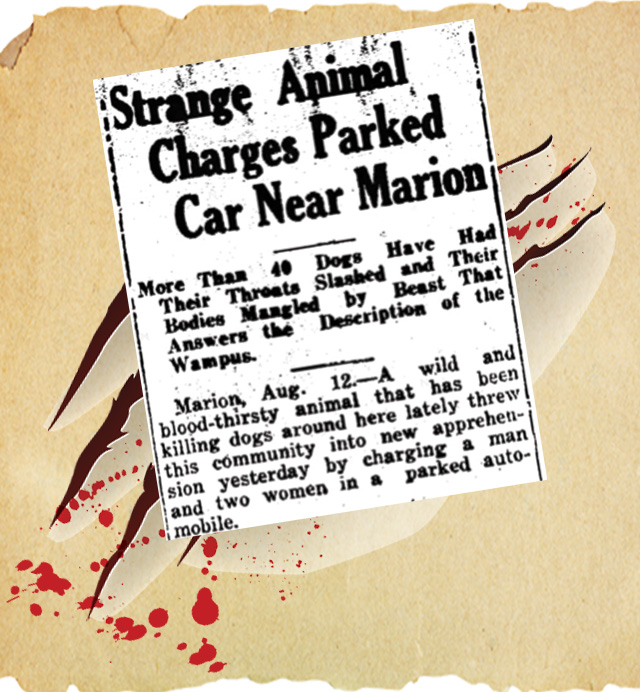

In the 1930s, sightings of so-called Wampus Cats were reported in and around the mountains.

The Wampus Cat: "A blood-thirsty animal"

Watch out: a kitty more terrifying than the one in Stephen King’s Pet Sematary might be roaming North Carolina, wreaking havoc in the dead of night.

Called the Wampus Cat, or sometimes simply the Wampus, the creature is unconfirmed but crops up in stories dating back decades. It’s purportedly much bigger than the average feline, with ferocious teeth and a yen for slaughtering domestic animals and scaring the bejesus out of humans.

The mystery critter once caused quite a stir in Western North Carolina’s foothills, as firsthand accounts morphed into a rumorous wildfire.

In August of 1932, for example, a local newspaper reported that a suspected Wampus had slashed and mangled more than 40 dogs in and around Marion. The “blood-thirsty animal,” according to one eyewitness, “had long, slim legs, sharp pointed ears, [and] a large head.”

The beast was never killed or apprehended, though it surfaced in a spate of additional stories at the time. Some speculated that it was a hyena escaped from a zoo. Whatever it was, it was hardly an isolated specter.

“During the 1920s-30s, newspapers reported of a ‘Wampus’ cat killing livestock in North Carolina to Georgia,” notes Wikipedia’s entry on this curious potential cryptid. “Though possibly due to early intrusions of coyotes or jaguarundi, the livestock deaths were attributed to the Wampus cat.”

Perhaps the Wampus is strictly a folkloric creation—and let’s hope so.

The Pink Lady: Zelda Fitzgerald’s rosy ghost?

An encounter with a rosy-hued prankster of a ghost might just be one of the most memorable experiences for a visitor to one of Asheville’s most famous hotels. The apparition is known as the Pink Lady. The hotel is the grand Omni Grove Park Inn. And the lore has withstood the scrutiny of a well-known ghost hunter who also happens to be an Asheville native.

The tales, still foggy, begin with the supposed death of a young woman, perhaps in the early 1920s, perhaps a few decades later. Several eyewitness reports put encounters with the specter in room 545, near where, legend has it, a guest fell to her death from the fifth floor Palm Court Atrium.

Was the woman a debutant who accidentally went over the edge? Or a housekeeper trysting with a married man who, upon learning of her pregnancy, shoved her to preserve their secret affair? Perhaps. Yet another theory posits that the phantom presence is that of the once-vivacious Zelda Fitzgerald, an artist and writer in her own right who was married to one of the most famous authors of his day, F. Scott Fitzgerald. The author languished in a funk at the inn toward the end of his career (staying in rooms 441 and 443), while she perished in 1948 during a horrible blaze that consumed Highland Hospital just a few miles away.

Regardless of the possibilities, the stories collected by paranormal investigator Joshua P. Warren point to the persistent appearance of an ethereal entity at the inn. Warren, author of Haunted Asheville, interviewed some 50 people about the case, about half of whom claimed a direct interaction with the Pink Lady.

It seems she frequently manifests as a young woman wearing a pink dress, or simply as a pinkish vapor. She has a penchant for sometimes tickling feet, moving guests’ belongings, turning lights on and off, and making quiet contact with children, according to the stories.

Hardly the stuff of horrific poltergeists, to be sure, so have no fear: should you encounter this friendly ghost-guest at Asheville’s century-old inn, she’ll be pretty in pink and fleeting as a firefly.

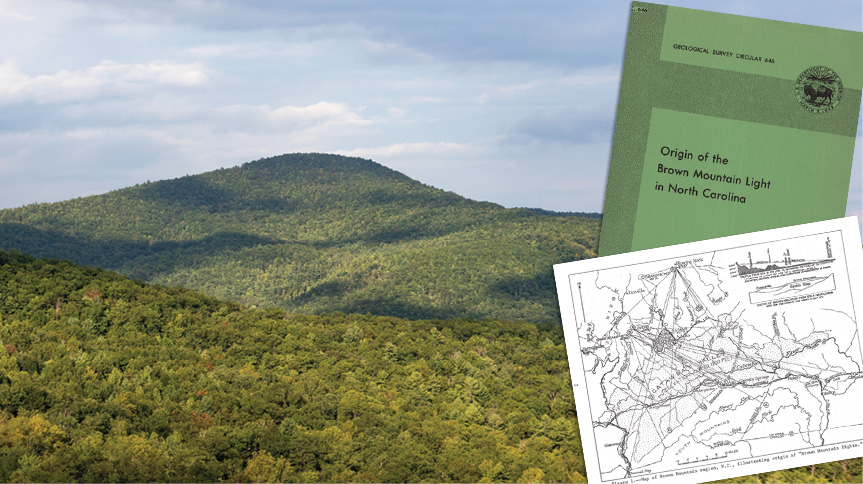

By the 1920s, interest in the strange lights prompted the US Geological Survey to conduct an in-depth study of the phenomenon and map potential sources.

The Brown Mountain Lights: “Weird, wavering lights rise above this mountain”

It’s a rare US Forest Service sign that bears words as unusual as the ones that long graced one Western North Carolina overlook:

The long, even-crested mtn. in the distance is Brown Mtn. From early times people have observed weird, wavering lights rise above this mtn., then dwindle and fade away.

The strange atmospheric phenomenon known as the Brown Mountain Lights has been discussed, documented, and dramatized over hundreds of years. It remains one of the Blue Ridge Mountains’ most enduring mysteries. The sometimes multicolored lights have appeared most often in the fall, dancing around the peak of Brown Mountain. Cherokee Indians and the settlers who followed them passed on stories of sightings around the Burke County mountain, located in the vast Pisgah National Forest about 60 miles east of Asheville.

Modern-day scientists and hordes of curious onlookers have issued eyewitness reports from the Linville Gorge area near Morganton. Pop culture has helped mythologize the lights, from balladeer Sonny James’ “(Legend of) Brown Mountain Light” in 1962 to the The X-Files paranormal investigative team’s foray in a 1999 episode.

The stories run the gamut: ancient legends describe ghostly figures carrying torches in search of lost Native American souls; settlers described luminous vapors; biologists posit a phosphorescent light connected to the insects, animals, and fungi of the foothills’ forestland; weather specialists wonder if the lights could be “ball lightning,” an atmospheric electrical phenomenon; and interstellar thinkers openly wonder whether alien visitors in UFOs keep returning to this dark stretch of mountain land to share a little glow.

Throughout the speculation, a definitive scientific explanation has remained elusive. Both the US Weather Service and the US Geological Survey have investigated, and other inquiries are ongoing. Within the past decade, a professor of physics and astronomy at Appalachian State University marshaled students and fellow scientists to create a research group that trained infrared- and low-light sensitive cameras on the mountain. They managed to capture glimpses of the unexplained lights. But they still can’t explain them.

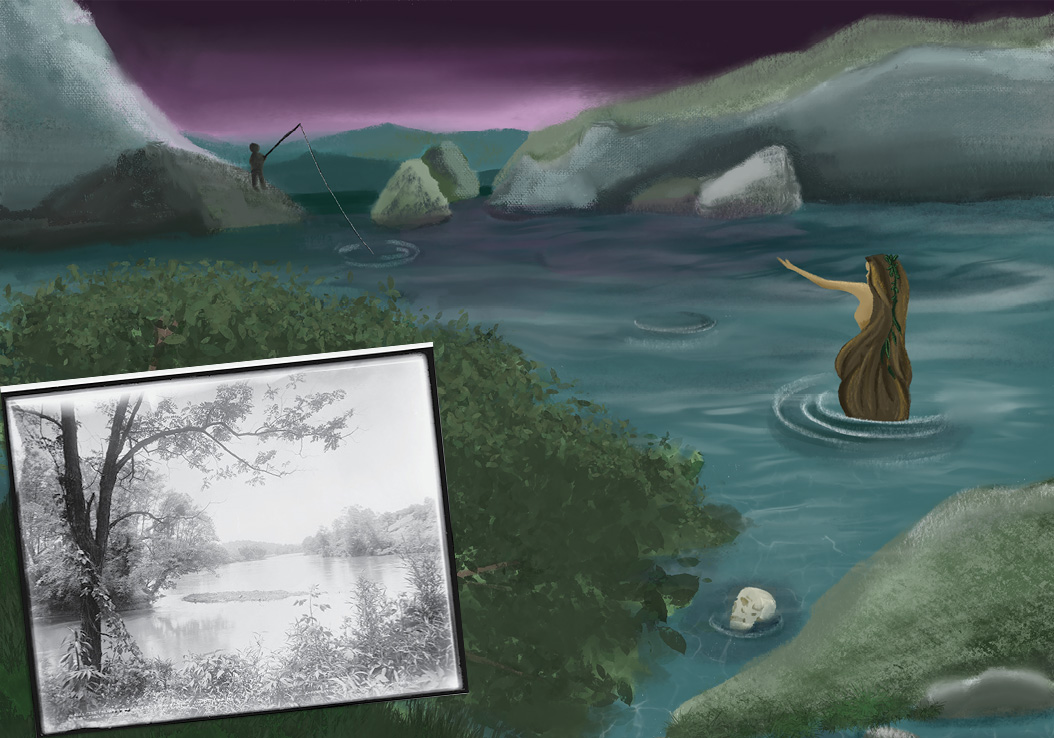

The Siren of the French Broad: “Among the rocks east of Asheville ... lives the Lorelei”

Said to be born from a Cherokee legend, the story of the French Broad River’s lethal temptress spread far and wide, especially from an 1898 retelling by Charles M. Skinner. An author from New York who delighted in sharing America’s edgy folklore, he enshrined the tale in his book Myths and Legends of Our Own Land (Volume 5): Lights and Shadows of the South. Early in it, he references a German yarn about a “Lorelei” who enticed fishermen to their deaths as a key reference point:

“Among the rocks east of Asheville, North Carolina, lives the Lorelei of the French Broad River. This stream—the Tselica of the Indians—contains in its upper reaches many pools where the rapid water whirls and deepens, and where the traveler likes to pause in the heats of afternoon and drink and bathe. Here, from the time when the Cherokees occupied the country, has lived the siren, and if one who is weary and downcast sits beside the stream or utters a wish to rest in it, he becomes conscious of a soft and exquisite music blending with the plash of the wave.

“Looking down in surprise he sees—at first faintly, then with distinctness—the form of a beautiful woman, with hair streaming like moss and dark eyes looking into his, luring him with a power he cannot resist. His breath grows short, his gaze is fixed, mechanically he rises, steps to the brink, and lurches forward into the river. The arms that catch him are slimy and cold as serpents; the face that stares into his is a grinning skull. A loud, chattering laugh rings through the wilderness, and all is still again.”