Leading Ladies of Past and Present

Leading Ladies of Past and Present: Nineteen influential women who have had a positive impact on Western North Carolina

Home Grown - One preservation concept for Nina Simone’s (pictured above) home not only involves retaining authenticity, but aims to revitalize the location with live performances, artists in residency, tours, and more. savingplaces.org

This spring, we’re shining a spotlight on some of the extraordinary women, past and present, who’ve dedicated themselves to the betterment of our region. From leaders in education, health, and the environment, to trailblazers in the arts and agriculture, these women have left an indelible mark on the people and places of our home. Without their efforts, Western North Carolina wouldn’t be the vibrant, extraordinary place that it is today.

Nina Simone {February 21, 1933-April 21, 2003}

Nina Simone once said that her musical talent wasn’t something she acquired, “It was a gift from God.” Born Eunice Kathleen Waymon in 1933 in Tryon, she learned to play the piano before the age of five, displaying her talent at a local church. Her gift was recognized locally, and with community support, she was able to attend The Allen School in Asheville, a college-prep boarding school for Black students from around Western North Carolina. After graduating in 1950, she attended The Juilliard School in New York, intent on becoming a classical pianist. Later, she sang in clubs, changing her name to Nina Simone so that her family wouldn’t find out that she was a jazz singer. As the Civil Rights Era progressed, Simone became increasingly politically active. “As far as I’m concerned,” she once said, “an artist’s duty is to reflect the times.” Her dynamic performance style earned her the nickname “The High Priestess of Soul.” Simone’s childhood home in Tryon is being restored by The National Trust for Historic Preservation with the aim of opening it to the public in 2024.

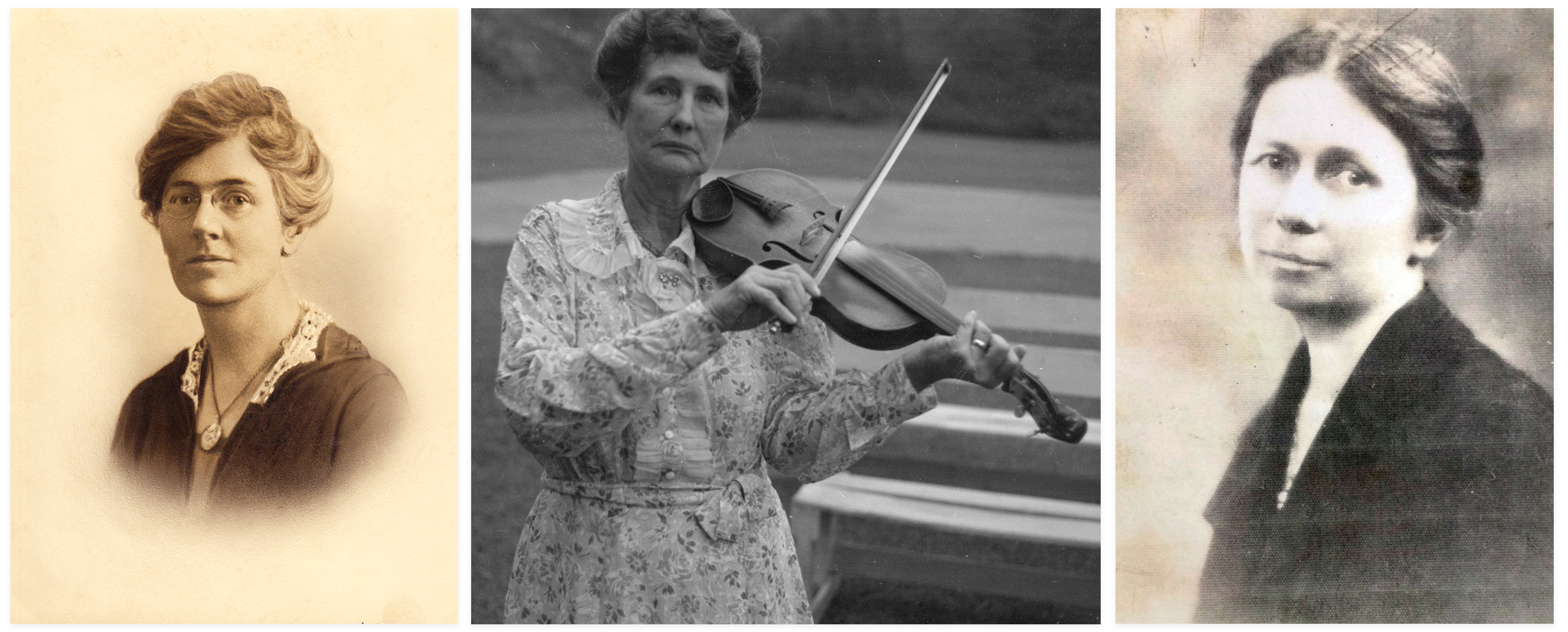

(Left to right) Olive Dame Campbell; Samantha Biddix Bumgarner; Dr. Mary Martin Sloop

Olive Dame Campbell {1882-1954}

Born in Massachusetts, Olive Dame Campbell came to the mountains with a wave of progressive educators who arrived in the region around the turn of the 20th century, determined to help the Appalachians who were living in poverty. She was among the first “songcatchers” who collected and transcribed traditional mountain ballads. She and her husband John Campbell arrived in Asheville in 1913. Around this time, the Campbells learned about the Danish concept of the folk school, promoting the idea of learning for learning’s sake. After John died, Olive finished his work and traveled to Scandinavia for nearly two years to learn about the folk school concept. After returning to the US, she started the John C. Campbell Folk School in 1925. The first students arrived in 1927, and nearly 100 years later, it’s now the largest folk school in the US, attracting students from around the world. “Education should not discredit such labor, but should give meaning breadth and depth. It should link culture of toil and culture of books . . . It should be enlightened action,” Campbell once wrote.

Samantha Biddix Bumgarner {October 31, 1878-December 24, 1960}

Born into a musical family, Samantha Biddix taught herself to play her father’s instrument—a fiddle—and later did the same with a banjo fashioned from gourd with a cat’s hide stretched over it, fitted with beeswax-coated cotton strings. In 1924, she traveled to New York to record a traditional Appalachian record, the first female banjo player to do so. She became a regular on old-time music radio shows, and at Bascom Lamar Lunsford’s Mountain Dance and Folk Festival.

In 1939, she traveled to the White House with Lunsford, and met and performed for President Roosevelt and King George VI of England. Bumgarner lived outside Sylva for many years, mentoring young fiddle and banjo players. Folk legend Pete Seeger said she inspired him to learn the banjo. “I’ll never forget Mrs. Bumgarner, sitting back in her rocking chair with a banjo,” he once said. “Oh, she’d painted the head of her banjo with brightly colored butterflies and flowers, and she was singing funny songs, tragic songs, violent songs, ‘Pretty Polly,’ about murdering your true love.”

Dr. Mary Martin Sloop {March 9, 1873-January 13, 1961}

Prospects were dim for children in the mountains around the turn of the 20th century. Schooling was compulsory for only four months of the year, but even that guideline was not rigorously enforced. There were few public schools to serve the population. Dr. Mary Martin Sloop was determined to do her best to change that.

As a graduate of Davidson College and the first woman admitted to the North Carolina Medical College, she and her husband settled in Crossnore and dedicated their lives to, “taking healthy swings at disease and poor diet habits, poverty through lack of opportunity, illiteracy, superstition, and all the other ills,” that held back, “these fine mountain people,” she said. The cornerstone of this mission was the founding of the Crossnore School. Under her direction, the academy grew from a one-room schoolhouse to a 20-building complex offering nine-month, eleven-grade education, taking in orphaned and homeless children. She described herself as, “tough as pine knot,” and, “able to take a lot of licks,”—ideal requirements for someone who set out to achieve lasting change.

(Left to right) Lucy Saunders Herring; Lillian Exum Clement; From left to right - Tribal Council Member Adam Wachacha, Ella Bird, former Principal Chief Sneed. The group stands in front of UNCA’s Bird Hall residence; & Myrtle Driver Johnson

Lucy Saunders Herring {October 24, 1900-October 1995}

In her early years as an educator at Hill Street School in Asheville, Lucy Saunders Herring wasn’t required to simply teach—she also had to raise money to buy books for her students, as Black schools didn’t receive funding from the government. But, she said she, “couldn’t afford to be frustrated—we had to keep a clear head.” There were no buses for Black students, so she organized parental support to buy a secondhand one. Throughout her career, she led Mountain Street School and Stephens-Lee High, and served as supervisor for the Black schools in Asheville and Buncombe County. Herring was known for her investment in every student, visiting parents at home when a student fell behind. One of the most impactful educators in Asheville’s history, she has had two schools named after her, the first of which—located on Mountain Street—closed in 1970 when Asheville schools desegregated. Although the schools she led were always under-resourced, she told The Asheville Citizen-Times that, “From the standpoint of instruction, our schools are just as good” as the white schools.

Lillian Exum Clement {March 12, 1886-February 21, 1925}

Although she lived only to age 38, Lillian Exum Clement’s outsize influence on North Carolina women in politics is still felt today. Born near Black Mountain in 1866, She studied law with private tutors in her spare time and passed the bar in 1916.

In 1917, she became the first woman in the state to practice law without male partners, focusing on criminal law from her Asheville office. Just as the national movement for women’s suffrage had met with success with the ratification of the 19th amendment, she was nominated as Buncombe County’s Democratic representative to the North Carolina General Assembly. She won by a landslide, becoming the state’s first female legislator in 1921. She used her position to sponsor legislation important to women and girls. Exum Clement was conscious of her role as a leader, telling the Raleigh News and Observer, “I want to blaze a trail for other women. I know that two years from now there will be many other women in the legislature. But you have to start a thing, you know.” Today, the progressive PAC, Lillian’s List, bears her name, devoting much of its efforts to mentoring and training women across the state to run for office.

One for the Books: Clement introduced a variety of progressive bills during her tenure, such as the Pure Milk Bill that required dairy herds to be tested for tuberculosis, and the Clement Bill, which called for the use of secret ballots.

Ella Bird {present day}

Ella Bird was bestowed the title “Beloved Woman” by the Eastern Band of Cherokee Tribal Council in 2013. Born in the West Buffalo area of Graham County’s Snowbird community, she earned a reputation for her quilting artistry, and for her commitment to preserving the Cherokee way of life, all while raising 10 children. Bird is also known for her adherence to the Cherokee language, which she speaks almost exclusively, with nuance and poetry. “She embodies and personifies what it truly means to be a Cherokee elder,” former EBCI Principal Chief Richard Sneed said of her in 2021. “She is esteemed by her children, community, and tribe, and she is beloved by her people because she has consistently modeled what it means to be Aniyvwiya—The Principal People.” Bird received an honorary doctorate degree from the University of North Carolina Asheville in 2017, where a residence life hall was renamed after her in 2021.

What is a Beloved Woman? Those who are bestowed this honor have made uniqe contributons to the Cherokee people. They are also known as “War Women,” since the title was originally for female warriors who had protected their tribe.

Myrtle Driver Johnson {present day}

In the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians, there are only around 200 native language speakers (those who grew up speaking it as their first language in the home). But thanks, in large part, to the efforts of Myrtle Driver Johnson, young Cherokee children are learning the language, keeping it alive for future generations. When Johnson was growing up in the Big Cove community, everyone spoke Cherokee, except at school, where Cherokee children were required to speak English.

While she lived away for a long time, Johnson returned to the Qualla Boundary in the 1980s. Not long after, she realized her native language was dying. Since then, she has helped establish the Cherokee-immersion New Kituwah Academy, translated children’s books and textbooks into the Cherokee language, and served as translator for the tribal council. In 2007, the EBCI conferred Johnson the title of Ghigau or Beloved Woman, a great honor. She is now one of only two living members to hold the title, the other Ella Bird.

(Left to right) Dr. Mary Frances Shuford; Jennifer Pharr Davis; Wilma Dykeman & Karen Cragnolin Park

Dr. Mary Frances Shuford {May 23, 1897-June 7, 1983}

In segregated Asheville, the only hospital for Black citizens closed in 1929 due to lack of funding. For more than a decade, those in need of medical care were consigned to a 21-bed area in the basement of Mission Hospital, meaning that many of the city’s nearly-15,000 Black residents were denied life-saving treatment. Calling the situation, “truly deplorable,” Dr. Mary Frances Shuford dedicated her career to changing it. Known to her friends as Polly, she was one of a handful of women to attend Columbia University’s medical school in the post-World War I period. She raised donations to start the Shuford Colored Clinic on College Street, performing 200 operations and seeing 2,000 patients in her first year. She then began a successful campaign to open the Asheville Colored Hospital in 1943 on Biltmore Avenue (in what’s now the South Slope), later helping to create the Stumptown Community Center which opened near the current Montford Community Center in 1968.

Jennifer Pharr Davis {present day}

Among her many accomplishments, Davis has hiked more than 14,000 miles of trails on six continents, set the overall record on the Appalachian Trail by averaging 47 miles a day and finishing it in 46 days, the first and only woman to hold this title. She has hiked in all fifty states with a toddler, published eight books, been named a National Geographic Adventurer of the Year, and was one of Men’s Journal’s 25 Most Adventurous Women of the Past 25 Years. She was named to the President’s Council on Sports, Fitness, and Nutrition the same year, and is featured in the 2020 film Into America’s Wild. “Spending time outdoors in the Southern Appalachians has taught me the beauty and strength of biodiversity,” she says. “The most resilient communities are the ones that create space for others to thrive.” In 2008, she founded The Blue Ridge Hiking Company, which she sold last year, so she can pursue a master’s in public affairs from UC Berkeley and start a nonprofit called Crossing Our Divide, focused on land use and politics and the way we bridge political and cultural gaps.

Wilma Dykeman {May 20, 1920-December 22, 2006}

As a child growing up in Asheville, Wilma Dykeman always wanted to be a writer. After attending Asheville-Biltmore College (now UNC Asheville) and working part-time at Kress’s downtown, she got a scholarship to attend Northwestern University. When she returned home to Asheville shortly after graduation, Thomas Wolfe’s sister, Mabel, introduced her to James Stokely Jr., the man who would become both her husband and writing partner. In 1955, Dykeman published The French Broad, part of the iconic “Rivers of America” series. It was a time when the links between health, quality of life, and the environment were just entering into national discussion. She went on to write over a dozen books, including three novels and several nonfiction books about race relations in the South (with Stokely), the people of the Southern Appalachians, and a biography. “Just as the river belongs to no one, it belongs to everyone and everyone is held accountable for its health and condition,” she wrote, far ahead of her time.

A Lasting Legacy: In her honor, UNCA began a writer-in-residence program in 2023. Recipients stay in Dykeman's Asheville home while collaborating with the university and community at large.

Karen Cragnolin {May 19, 1949-January 2, 2022}

Whether walking, running, or biking along the Wilma Dykeman Greenway in the River Arts District, those enjoying the trail may not be aware of the hard work, persistence, and dedication that made it happen, led by Karen Cragnolin, the founder and long-term director of Asheville nonprofit RiverLink. At the organization she founded in the 1980s, Cragnolin worked to elevate public awareness of the importance of protecting the French Broad, and led the charge for riverfront redevelopment that would provide public access. Cragnolin engaged with stakeholders across the community to create a plan that would improve local quality of life, including the development of French Broad River Park and Carrier Park, along with the Greenway. A medical issue in 2016 led to her retirement, but she kept active until her death in 2022. A portion of Carrier Park now bears her name. “When I arrived in Asheville, I didn’t even know there was a river…The river wasn’t on anyone’s radar,” she wrote in Mountain Xpress in 2016. “We have come such a long way.”

(Left to right) Jean Williamson Webb with Karen Cragnolin; Sophie Dixon (right) with Shaniqua Simuel, navigator and garden co-coordinator of the Shiloh Community Association.; The Sandburgs with a dairy-producing goat & Thelma Caldwell.

Jean Williamson Webb {March 13, 1932-March 29, 2022}

Newcomers to Asheville may not be aware of the legacy of Jean Webb, a passionate advocate for the French Broad River and the area’s natural resources. An Asheville native, Webb got involved in the Land of Sky Regional Council’s river advisory committee in the 1970s, a time when industrial blight and waste had sullied the banks of the French Broad for decades. The river was not seen as a place for recreation—many used it as a dumping ground. Webb mobilized her fellow citizens to change that, organizing litter clean ups and, as her obituary stated, pulling countless tires and appliances from the river. Throughout her career, Webb headed Quality Forward (now Asheville GreenWorks) and the French Broad River Foundation while encouraging the community to take part in trash clean ups and recycling events. She advocated for public access points to the river, and the riverfront park bearing her name, established in 1988, was the first one since the flood of 1916.

Sophie Dixon {present day}

Among her many community contributions, Dixon has served as president of the Asheville- Buncombe County NAACP and as president of the Shiloh Community Association. In 2019, she was honored by the Asheville City Council as Volunteer of the Year. While born in Stumptown (now part of Montford), Dixon has lived in the Shiloh community for decades, helping develop and promote the community garden and leading the development of its roadside stand. She helped found both WRES radio and the Goombay Festival, and was a charter member of the YMI Cultural Center Board of Directors. In Shiloh, Dixon is known for her many efforts to foster intergenerational friendship and collaboration, and to find ways for new and long-time residents to connect. In 2022, Dixon was honored with the annual Rosa Parks Award, given by Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Association of Asheville and Buncombe County for her lifetime of serving the community.

Lasting Legacy: Asheville GreenWorks hosts Clean Streams Day each May. Volunteer paddlers journey along the city’s waterways, picking up trash and other debris, just like Webb did when she took her first steps towards river conservati

Paula Sandburg {May 1, 1883-February 18, 1977}

Although often defined by her relationship with famous men—her brother, photographer Edward Steichen, and husband, poet Carl Sandburg—Lillian “Paula” Sandburg was accomplished in her own right. A 1903 graduate of University of Chicago, Paula was active in the women’s suffrage movement. After buying her first goat in 1935, she delved into research about the health benefits of goat milk and established a reputation as a breeder. The Sandburgs moved to Connemara (just outside Flat Rock) in 1945, in part so that she could expand her goat dairy operations. At its height, Connemara Dairy was selling champion goats worldwide. After Carl died in 1967, Paula donated the family property to the National Park Service, which was the first national park dedicated to a poet. Throughout their nearly 60 years together, the Sandburgs wrote many letters to each other. In one, Paula said, “We shall do our best to leave something that we have produced here on Earth as a bequest.” For the many visitors who enjoy the park each year, the Sandburgs certainly achieved that.

Thelma Caldwell {October 1912-August 6, 2004}

Thelma Caldwell began her YWCA career as a teen program director in Wilmington, Delaware and her success there led to leadership positions all around the US and abroad. She arrived in Asheville to take the top spot at the Phyllis Wheatley Branch of the YWCA in 1961, on the cusp of extraordinary change for the city. The YWCA had long been a center of Black cultural life in Asheville, providing space for community groups and hosting plays, dances, and much more in addition to its athletics promotion.

Nationally, the YWCA had a stated mission of eliminating racism, but locally, the facilities were still segregated. Caldwell began the years-long process of integration in part by hosting community dialogues and integrating swimming lessons and evening activities. She led the community in the often-contentious work, and in 1967 became executive director of the increasingly integrated YWCA, the first black director of a YWCA in the South, and only the second national director. Later, she advised other YWCAs around the world on the process.

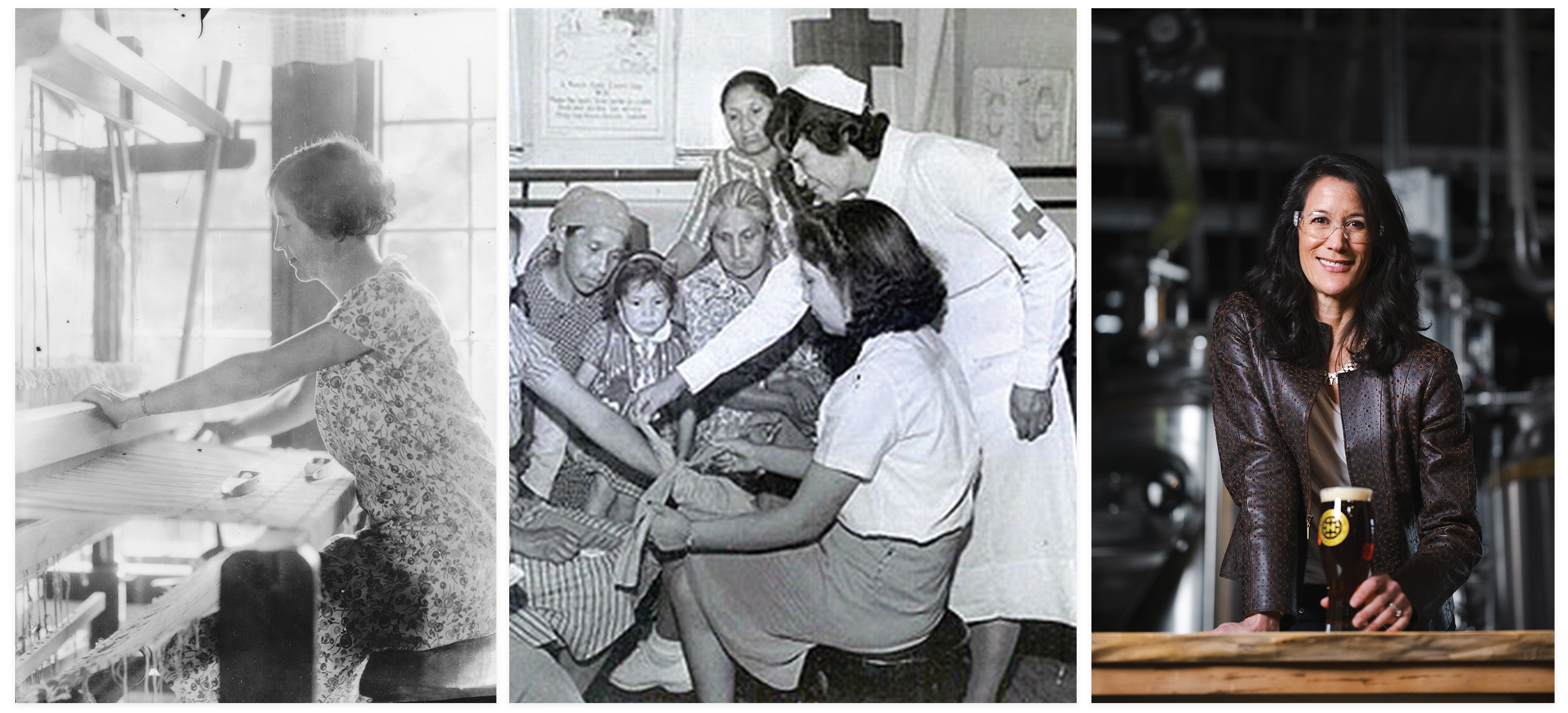

(Left to right) Lucy Morgan; Lula Gloyne’s first aid class & Leah Wong Ashburn

Lula Owl Gloyne {December 1891-April 17, 1985}

When she first began her career as a midwife, Lula Owl would take her horse or ox cart out to the home of patients in the most remote sections of the Qualla Boundary, providing the only medical care some of them would ever receive. She attended Hampton Institute, a historically Black college that was one of the only colleges in the US to admit Native Americans. After briefly teaching, she decided to pursue nursing, and graduated from the Chestnut Hill Hospital School of Nursing in 1916, making her the first Eastern Band Cherokee Indian (ECBI) Registered Nurse, and possibly the first Native American Registered Nurse in the United States. During World War I, she was the only ECBI officer to serve in the army, stationed at Camp Lewis in Washington. When she returned to Cherokee, she worked for the tribe without pay because she saw a need: there was no resident doctor on the Boundary at the time. She helped establish the first hospital with inpatient care in Cherokee, and in 1943, she was recognized as a Beloved Woman by the EBCI.

Lucy Morgan {1889-1981}

Unlike many of the progressive educators who came to the mountains to help the poor at the turn of the 20th century, Lucy Morgan was a native of Western North Carolina. She trained as a teacher, and in 1920, arrived to serve as principal at The Appalachian School in Penland, an Episcopal mission school. After visiting Berea College in 1923 and taking part in a weaving class there, she returned to Penland to start a cooperative weaving program to help local women supplement their incomes.

Later, the school (then named Penland School of Handicrafts) added classes on bookbinding, leather tooling, and pottery, and attracted students from outside the area. “Miss Lucy,” as she was called, worked tirelessly to promote the work of the crafters, traveling all over the country to represent their work. In 1933, she famously drove a truck fitted with a “tiny house” to the Chicago World’s Fair to publicize the work of Penland weavers. Morgan’s passionate advocacy for craft and makers had an impact far beyond the school, helping to make Western North Carolina a national center for all things handmade.

Leah Wong Ashburn {present day}

Brewing is an overwhelmingly male business, but in her role as president and CEO of Highland Brewing, Leah Wong Ashburn has changed the culture. “Leadership brings privilege,” she says. “Being a woman leader in craft beer allows me to speak more directly to our staff—which is 40 percent women—and industry about issues in the workplace.” During her tenure at Highland, the percentage of women in management roles at the company has increased to 50 percent. Under her leadership, the company has expanded their distribution throughout the South, brewing six seasonal beers and special releases in addition to its flagship products.

The brewery’s 40-acre campus and solar-powered event space has become a mainstay of Asheville’s social scene, promoting the company’s emphasis on a love of the outdoors. Ashburn’s father, Oscar Wong, founded the company in 1994, pioneering the craft brewery industry in Western North Carolina. Like him, she’s a pioneer, too. “I hope more women continue to join and lead in beer,” she says.