Centuries Ahead

Centuries Ahead: As the nation celebrates Frederick Law Olmsted’s 200th birthday, witness the creation—and evolution—of his visionary Biltmore landscapes

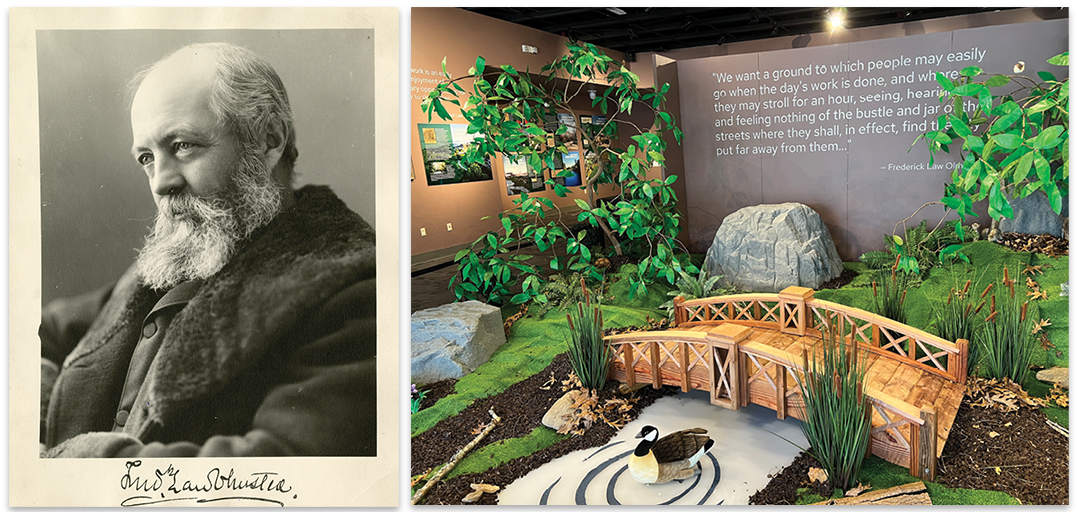

Come this April 26, kindly take a moment to step outside, preferably to your favorite public park, and say a word of thanks to Frederick Law Olmsted. The man widely regarded as the father of American landscape architecture was born this day 200 years ago, and he remains an indelible part of some of the nation’s most memorable scenery and outdoor reposes. Throughout this year, he’ll be honored at his creations and co-creations ranging from New York City’s Central Park to the US Capitol grounds to many of the country’s oldest state parks and parkways, in a nationwide celebration dubbed Olmsted 200: Parks for the People.

In Western North Carolina, accolades for Olmsted will sound fervently across the grounds of Biltmore, a labor of love for Olmsted and one of his last great endeavors. Tasked by the young scion George W. Vanderbilt with designing his family’s southern retreat—with virtually no expense spared and with an eye towards developing a lavish but nature-embracing estate—Olmsted set about the task with relish and was soon joined in the endeavor by some of the nation’s greatest architects, builders, civil engineers, and foresters.

Biltmore “is far and away the most distinguished private place, not only for America, but of the world, forming at this period,” Olmsted advised his partners early in the project. “It will be critical and reviewed and referred to for its precedents and for its experience, years ahead, centuries ahead.”

Olmsted’s handiwork is evidenced in every nook and cranny of the estate, to this day. As the nation embraces and salutes his legacy, more than a century after he designed in Biltmore his final masterwork, we revisit his formative vision for Vanderbilt’s sprawling, world-famous domain by mining Olmsted’s voluminous archives—letters, sketches, surveys, maps, design plans of all stripes—along with rare photos taken by his firm and others who were there at the creation.

Parker Andes, Biltmore’s director of horticulture, relies on these primary sources to maintain and improve the grounds, even today. “That’s actually one of the better parts of my job, to tell the truth,” he says. “That’s how we make a lot of decisions—the photography and the letters are the most factual guide to what things are supposed to look like, to what we’re supposed to be doing. We maintain the things that we know were essential back then to Mr. Vanderbilt’s guests’ experience, and we strive to find whatever has been lost and recreate it.”

Through the lens of these original plans, we can see just how far Biltmore has come, and how Olmsted’s dreams for this most remarkable place are now a vivid and lasting reality.

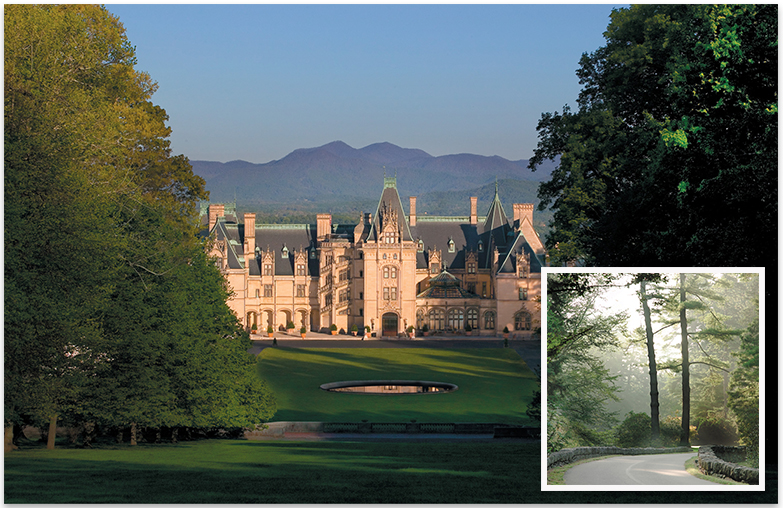

In Vanderbilt’s service, Olmsted and Hunt functioned as a dream team, melding their visions for the grounds of the estate and the spectacular house. The two men had worked together on previous projects, and by all accounts reached clear accord on their main objectives for the property and the residence, the results of which are on grand display today; (Inset) Biltmore’s approach road, in all its glory. Aside from the asphalt, much of the route remains as Olmsted envisioned it, serving as a conduit to another world and providing the “striking and pleasing impression” he sought.

The Approach Road

Olmsted was determined that Vanderbilt’s guests would have much to marvel at long before they even reached Biltmore’s huge and stately chateau. The three-mile approach road, starting in Biltmore Village and wending through serene passages of the estate, would be a crucial element of the overall plan for the land. This liminal passage would set the stage for all who visited Biltmore, framing their overall experience with a wondrous entrance.

“I suggest that the most striking and pleasing impression of the Estate will be obtained if an approach can be made that shall have throughout a natural and comparatively wild and secluded character,” Olmsted wrote to Vanderbilt in the summer of 1889, “its borders rich with varied forms of vegetation, with incidents growing out of the vicinity of springs and streams and pools, steep banks and rocks, all consistent with the sensation of passing through the remote depths of a natural forest.”

The scenic journey would heighten the anticipation for the revelation to come at the end of the approach route: “Such scenery to be maintained with no distant outlook and no open spaces spreading from the road; with nothing showing obvious art, until the visitor passes with an abrupt transition into the enclosure of the trim, level, open, airy spacious, thoroughly artificial Court, and the Residence, with its orderly dependencies, breaks suddenly and fully upon him.”

The sensation, just as Olmsted had planned it, remains the same today.

The Home Site

Perhaps Vanderbilt and Olmsted knew it the moment they saw it: from atop Biltmore’s rolling hills, majestic views of the surrounding mountains, particularly to the west, were in great abundance. Accordingly, they reasoned, the placement of the home site must, above all else, embrace the opportunity to provide stunning and serene views.

Olmsted had long prioritized the pleasures of gazing on a gracefully appointed landscape. “The enjoyment of scenery employs the mind without fatigue and yet exercises it, tranquilizes it and yet enlivens it,” he wrote in 1865, “and thus, through the influence of the mind over the body, gives the effect of refreshing rest and reinvigoration of the whole system.”

Vanderbilt chose New York architect Richard Morris Hunt—already a frequent collaborator with Olmsted and the Vanderbilt family—to design the majestic house, and he agreed on the need to stage the home with views top-of-mind. Together these lions of design pored over topographic maps of the estate-in-the-making and seized on a promising spot—but one that would need considerable work.

“You will observe that the scope of the scenery to be enjoyed from the house will be much enlarged by cutting down the crest of the hill-top on the East and by breaking into the woods on the North,” Olmsted reported to Vanderbilt. Much leveling and moving of earth would be required to perch the home just right for capturing views of Mt. Pisgah and its lesser neighbors, but Vanderbilt was quick to approve the plan.

Over and over, Olmsted reworked his plans for Biltmore’s distinctly different but complimentary gardens.

The Gardens

Naturally, the spaces immediately surrounding the home were a prime concern—and a grand opportunity—for Olmsted and his colleagues. It was there that Vanderbilt and his guests would most often stroll the grounds, and a house of such spectacular proportions and quality would need gardens to match.

On one side of the home, Olmsted envisioned what he called the Ramble—“a glen like place with narrow winding paths between steepish slopes with evergreen shrubbery.” This space came to be known as the Shrub Garden.

Nearby, Olmsted designed other distinct landscaped areas: the Italian Garden, with three symmetrical reflecting pools and elegant sculptures; the Walled Garden, a four-acre spread rife with flowers and themed areas (Olmsted originally planned for this to be a fruit and vegetable garden); the Rose Garden, featuring more than 200 varieties of roses; and a 15-acre Azalea Garden.

Nowadays, throughout the year—and especially during the annual Biltmore Blooms festivities in spring—Olmsted’s gardens are as stunning as he likely hoped they would be.

Water Features

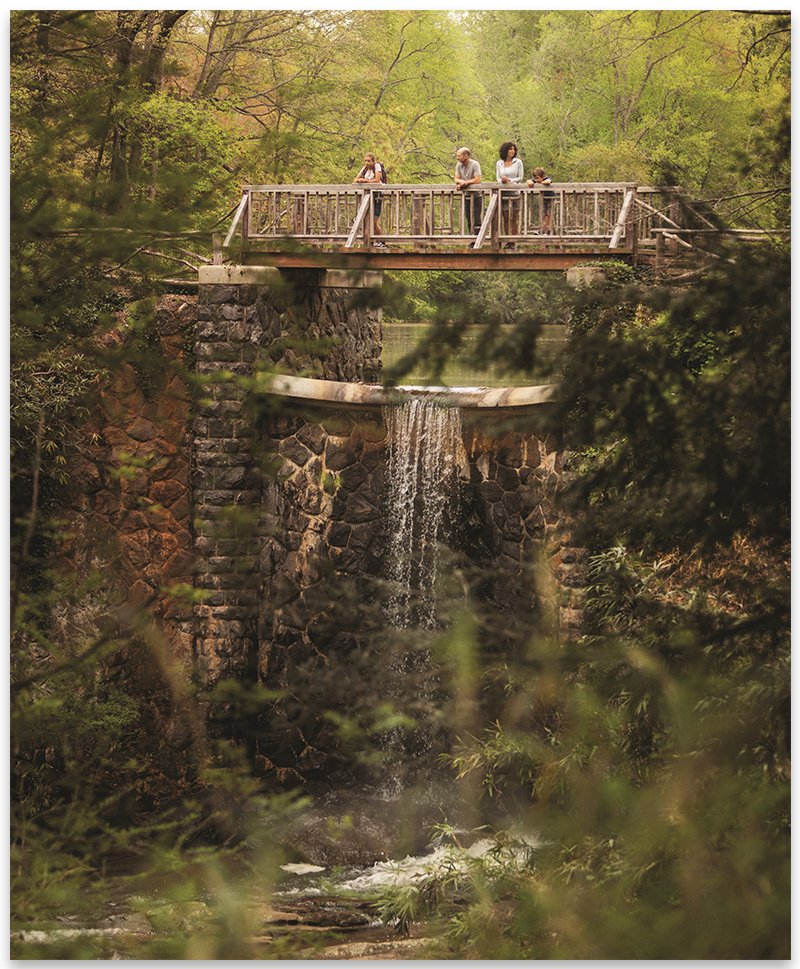

As much as Olmsted labored over designing the land at Biltmore, he sought to shape and enhance the estate’s water features. The French Broad River, which snakes through the estate, figured in many of his plans for irrigation, drainage, and agriculture. Manmade fountains would help adorn the mansion’s grounds. And several small ponds—some already in existence, some to be cultivated and augmented—would become vital threads in Olmsted’s tapestry.

Parker Andes, Biltmore’s director of horticulture, is likewise focused on the estate’s liquid assets. In fact, he’s presently engaged in the restoration of a small island in the Bass Pond. Originally, the pond had two islands—Olmsted correctly predicted that they’d be great habitat for waterfowl—but only one remains today. The other “was obviously there in 1895, you can see it in the pictures,” Andes notes. “So we decided to recreate that island. It’s supposed to be there.”

The Forests

“I was at my first visit greatly disappointed with its apparent barrenness and the miserable character of [Biltmore’s] woods,” Olmsted informed a colleague in one letter. In another, he complained of the “extremely poor and intractable” soil and declared that the grounds would have to be built “out of the whole cloth.”

The answer, Olmsted determined, was to make Biltmore the home of unparalleled efforts in forestry. He wooed Vanderbilt with the idea in a letter: “A well managed forest is likely to be as good a property, all things considered[,] as any other. Mean time, the management of it; the oversight of its development and improvement from year to year, would be a most interesting rural occupation; far more interesting, I am sure, to a man of poetic temperament than any of those commonly considered appropriate to a country-seat life. Certainly there can be no prospect of success, of profit or pleasure from year to year, in any other use to be made of your ridge lands to compare with it.”

Vanderbilt was persuaded by Olmsted’s logic, and the rest, to paraphrase a saying, is forestry history. On Olmsted’s recommendation, Vanderbilt hired the noted scientific forester Gifford Pinchot, who set about restoring and diversifying Biltmore’s tree stock with a focus on the long view. In 1895, Pinchot departed the project and was replaced by German forester Carl Schenck, who founded the Biltmore Forest School, the nation’s first academic institution devoted to forest conservation and management. Biltmore, then, can rightly claim to be the Birthplace of American Forestry—yet another legacy that would have made Olmsted proud.

Olmstead 200 at Biltmore

This year, Biltmore will honor Olmsted in multiple ways to mark his two-century legacy. It’s a prime opportunity to celebrate the visionary who shaped these grounds into the history books—and to write still more chapters of his lasting influence.

Olmsted Scenic Stops

On April 22, Biltmore will unveil a collection of scenic stops throughout its gardens and grounds to showcase Olmsted’s accomplishments at Biltmore and the mature and preserved landscapes that he envisioned more than a century ago. The stops will share stories about Olmsted’s plans and pass through areas including Deer Park Trail behind Biltmore House, the location of some of Olmsted’s signature design elements.

Olmsted 200th Birthday Moveable Feast

Also on April 22, Biltmore will host a unique dinner in an exceptional setting—the estate’s glass Conservatory—to mark Olmsted’s birthday. The festivities, which begin at 6 p.m., include a sparkling wine reception and a five-course feast paired with Biltmore wines.

Biltmore Blooms, April 1 to May 26

Olmsted would have gazed with delight on this annual tradition, which presents the house’s gardens in all their springtime glory and puts his design genius front and center. Tulips will pop in the Walled Garden, rose varieties will cast a rainbow of color, and other flowers, shrubs, and trees throughout the estate will burst into an aromatic symphony of blooms.

For tickets and reservations for all events, visit biltmore.com.

Thanks FLO: Celebrating Olmsted at the North Carolina Arboretum

If Olmsted had one great unrealized dream for Biltmore, it was that it would be home to a world-class arboretum. That element of his plan fell by the wayside as Vanderbilt’s financial fortunes shifted, but it was reborn in the 1980s with the establishment of the North Carolina Arboretum just south of Asheville. There, on 434 acres of land within Pisgah National Forest, picturesque plantings—some permanent, some ever-changing—grace the landscape in true Olmstedian fashion.

This spring, through May 8, the Arboretum will host Thanks FLO: Celebrating the Life and Legacy of Frederick Law Olmsted. The celebration has two components: a historical exhibit in Baker Visitor Center Exhibit Hall complemented by thoroughly modern, interactive stations, and a series of outdoor displays dedicated to Olmsted’s design principles.

For details, visit ncarboretum.org.