Trail of Tears National Historic Trail

Trail of Tears National Historic Trail

History

Besides winning the War of 1812’s most resounding victory, Andrew Jackson followed up with one of the United States’ most, “uncivilized,” acts, the near-genocidal eviction of the “Five Civilized Tribes” from their Southeastern homelands.

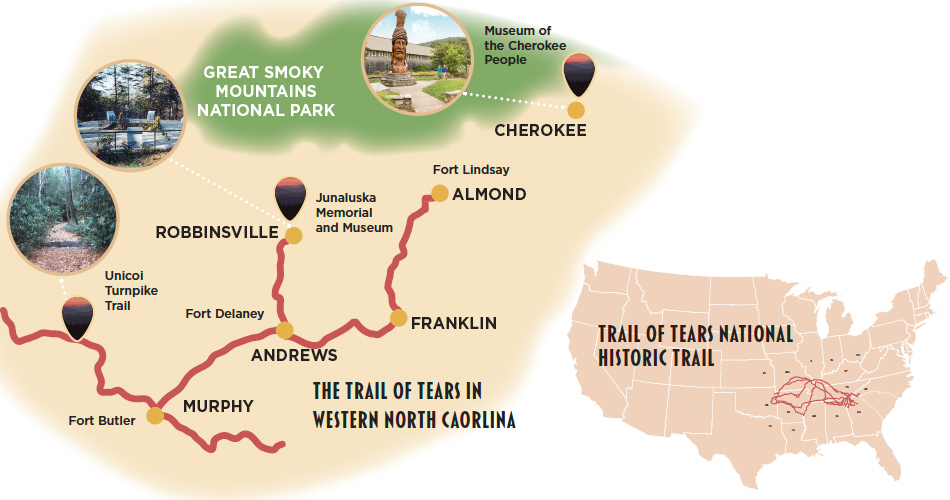

For the Cherokee, that ignominious Trail of Tears was sparked in 1835 when unauthorized Cherokees sold the tribe’s Southern Appalachian domain for $5 million, and made the pledge to move to “Indian Territory” in Oklahoma.By 1838, US Army forts near today’s towns of Andrews, Hayesville, and Robbinsville were gathering the refugees and funneling them through Fort Butler near Murphy over specially-built roads to “emigration depots” in east Tennessee. The forts are gone, but those routes, among the first wagon roads in Western North Carolina, are still visible today.

“Because of the remaining presence of the Eastern Band of the Cherokee, few people know the history of the 3,000 Cherokees who were forced to leave their homeland,” says Susan Abram, a history professor at Western Carolina University and president of the North Carolina Trail of Tears Association. That includes Cherokees who remained, principally those of Quallatown (near today’s Cherokee) who, by earlier treaty, were not subject to removal. Others vanished into the high mountains, avoiding capture to again become legal residents in the late 1860s. Today, what has become the Eastern Band has survived and thrived as the Qualla Boundary Cherokee Nation we know today.

(Left to right) On the long walk to Oklahoma, formal routes like this Illinois road told the Cherokees they were far from (the wilds of) their homeland; A marker honoring Sand Town’s first chief, Chuttatoee and his wife Cunstagih, who were also known as Jim and Sally Woodpecker.

Why Visit

The Trail of Tears, a National Historic Trail since 1987, doesn’t have a motorized route or a walking path like the Overmountain Victory Trail, but efforts are underway for, “a boots on the ground experience,” Abrams says. Nevertheless, “there are many interpretive wayside exhibits where visitors can learn more about the Cherokee Removal.” The rewards include scenic and historic locations where it’s easy to sense the pain of those who passed by on the murderous, late-1830s march to reservations west of the Mississippi.

Murphy, the central staging area for all the departing Cherokees, is home to the excellent Cherokee County Historical Museum. It’s certified as an interpretive center by the National Trail of Tears Association, and contains a fascinating collection of Cherokee artifacts. In Franklin, on the grounds of St. John’s Episcopal Church, a recently-dedicated exhibit highlights the location of a post-Removal Cherokee village named Sand Town.

In Cherokee, the Museum of the Cherokee People is the trail’s premier stop, but another stirring option is a visit to the memorial in Robbinsville that honors Junaluska, an important Cherokee leader during the 1800s. “Though forcibly removed,” says Abrams, “he later walked from Indian Territory back to his mountain homeland.” Indeed, the State of North Carolina granted him $100, state citizenship, and 337 acres of land.

It turns out, Junaluska was a veteran of the War of 1812, where his service against the Red Stick Creeks at the pivotal 1814 Battle of Horseshoe Bend helped finally quash British designs on America. Ironically, Junaluska fought under Andrew Jackson, and was credited with saving the life of the man who, as president, would later expel him. Junaluska and his family are buried here, and a museum displays Cherokee artifacts and contemporary Cherokee artwork.

Learn more

The North Carolina Trail of Tears Association is a nonprofit that supports the development and interpretation of the national trail. To learn more about the organization and the trail’s history, visit nctrailoftears.org.