Carving a Niche

Carving a Niche: In the centuries-old craft traditions of our area, the woodworking school at Haywood Community College may be a relative newcomer. But with more than 30 years of instruction, the intensive program continues to launch creative and highly skilled artisans into the world of furniture making and woodworking.

Anyone who’s shopped for handmade furniture knows that one surefire way to verify the quality of a piece is to pull out a drawer and inspect the joints. If the maker didn’t bother to dovetail them, there’s a better piece to be had. The dovetail is an ancient way of joining two boards, and its use—even in inconspicuous places—testifies to the builder’s skill.

It’s that facet of craftsmanship that a class of woodworking students are learning today at Haywood Community College. Each sits at a workbench with half-inch boards clamped into place. On both ends, they’ve sketched angled lines to mark where to cut and chisel to achieve pins and tails that fit together like two puzzle pieces. With small handsaws, they make slow passes, careful to ensure they don’t over cut or fall out of the scribed paths.

This is only the students second week of what will be a two-year intensive course in artistic and functional woodworking, which teaches at a level you wouldn’t expect to find at a technical school. For more than 30 years, this program—currently run out of HCC’s Professional Crafts building—has turned out some of the area’s most successful woodworkers and furniture makers.

“There are easier ways to cut a dovetail joint—we have plenty of power tools that make the job go faster,” says Brian Wurst, head instructor of the woodworking program. “But it’s important for students to learn how to do this by hand first.” It’s a lesson in controlling the tools, and learning how they respond as they pass through the wood.

Each student in his class spent time on an enrollment waiting list that can last a couple of years. And they’ve signed up to commit at least 18 hours per week (though Wurst recommends closer to 25 hours) in the shop for the next two years.

When they graduate, they’ll have gone through the equivalent of a master’s-level furniture-making course at a larger university. In fact, new HCC grads regularly enter work in the student competition at the International Woodworkers Fair in Atlanta—a contest that draws entrants from the top design schools in the country—and they often win awards.

CRAFTING A CAREER

While some of the students are hobbyists—retirees looking to expand their personal horizons—others hope to make this craft their livelihood. Mo Yarborough, for instance, hopes to retire from his career as a concert soundman to combine what he learns here with his knowledge of metalwork (a skill he developed in HCC’s Professional Crafts department) to create period reproduction furniture.

To get him there, the program will teach Yarborough much more than how to bring shape to pieces of wood. The students will learn how to become designers, drafters, and all-round entrepreneurs. “We’ve had a lot of people who’ve been through the program come back and say ‘I didn’t really think that marketing plan you made me create was much of anything, but it sure helped me get started,’” says Wurst. Students will leave with a business plan that they can take to a bank or investor for seed money, and they’ll even know how to set up studio lighting to photograph their pieces for catalogs and portfolios.

“This is a tough business,” says Wurst, acknowledging that furniture is a market typically ruled by mass production and competition. They’ll be competing with other talented woodworkers for the attention of a very select clientele. “I don’t think the folks who come here have giant dollar signs in their eyes. Most do it because they’ve been in other careers, and now they want to do something they love.”

It’s the customers attracted to Western North Carolina for its craft traditions that make this a viable vocational choice. The program started in the late 1970s. The original intention was to prepare students for jobs in the region’s many furniture factories.

But two things gradually changed: The high end of the market saw more demand for custom-built furniture at the same time as the factory jobs began to dissolve. It was during this period that the instructors, including Wurst’s predecessor, Wayne Rabb, redirected the program toward fine art—though there is still emphasis on teaching the basic principles of production. Wurst attributes this shift to buyers becoming more educated in their appreciation for the labor and skill that goes into handmade works.

BUILDING A NAME

One of the school’s graduates making inroads to that select clientele is Susan Link, who finished the program six years ago. Now, she’s working on a gigantic custom desk in her North Asheville workshop. “I don’t normally take on projects like this,” she says, referring to the five-piece creation that’s been taking shape since spring, “but I was commissioned by someone who has bought my furniture in the past, and needed a piece like this.”

Her work normally leans toward relatively smaller pieces like buffet tables, armoires, and chairs that stretch the lines of traditional arts and crafts designs, but with the dramatic visual appeal of Danish modern furniture. The symmetry she creates in each piece is punctuated by the grain of each domestic wood she uses, usually maple, cherry, and walnut.

She shares her workshop with Melissa Engler, a recent HCC graduate. Though their work is very different in style—Engler uses a more sculptural aesthetic in her tables and chairs—the two women have a lot in common. Link has reached a place in her career where she can mostly support herself on her woodwork, though she still puts in an occasional shift at Sunny Point Café (owned by her former instructor, Rabb).

Engler, on the other hand, is just getting started. She’s sold a few pieces through a show at the Blue Ridge Parkway’s Folk Art Center, and she’s recently had two entries win first place at the IWF competition. The prize money is what’s helping her get off the ground.

Her immediate launch plan includes finishing her website, networking with the area’s numerous professional crafts organizations, and spending as much time in the shop as possible. “My main interest is in developing my gallery work, which consists of speculative pieces where I can be freer with the design,” she says. “I know that commissions are eventually going to become part of what I do, but right now I’m trying to make these pieces very much my own.”

Wurst is a realist about what lies ahead for each of the graduates. Some will go on to work for other craftspeople, some will use what they’ve learned as a lifelong hobby, and a few from every class will make it on their own.

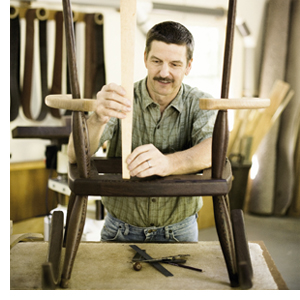

Distinguished Alumni: David W. Scott

I love being in my workshop,” says David W. Scott of the studio beside his home, “because it feels like I’m living inside a toolbox.” He just moved into the new space in Black Mountain a few months ago, roughly 30 years after completing his education at HCC—he was a student in one of the earliest classes to finish the woodworking program. Throughout the decades, he’s constantly updated and refined the curvilinear style in the tables, stools, shelves, and rockers that he sells through Ariel Gallery in Asheville. He also works on 10 to 12 custom projects during the year, building desks and other furniture based on his style. He’s also starting to incorporate nontraditional materials, such as bamboo tabletops, into his work. “It doesn’t matter how long I’ve been a woodworker, the process continues to be really fascinating for me.”

I love being in my workshop,” says David W. Scott of the studio beside his home, “because it feels like I’m living inside a toolbox.” He just moved into the new space in Black Mountain a few months ago, roughly 30 years after completing his education at HCC—he was a student in one of the earliest classes to finish the woodworking program. Throughout the decades, he’s constantly updated and refined the curvilinear style in the tables, stools, shelves, and rockers that he sells through Ariel Gallery in Asheville. He also works on 10 to 12 custom projects during the year, building desks and other furniture based on his style. He’s also starting to incorporate nontraditional materials, such as bamboo tabletops, into his work. “It doesn’t matter how long I’ve been a woodworker, the process continues to be really fascinating for me.”

www.scottwoodworking.com

Distinguished Alumni: Susan Link

The WNC native only had a week to rearrange her life when someone from HCC’s woodworking program called to say that a spot had just opened up at the last minute. With her days of working at a hospital long behind her, the 2004 graduate is developing a name for herself among the area’s custom woodworkers. Her style is a contemporary twist on arts-and-crafts furniture and can be found in many local galleries, including Grovewood Gallery in Asheville. www.linkwoodworks.com

The WNC native only had a week to rearrange her life when someone from HCC’s woodworking program called to say that a spot had just opened up at the last minute. With her days of working at a hospital long behind her, the 2004 graduate is developing a name for herself among the area’s custom woodworkers. Her style is a contemporary twist on arts-and-crafts furniture and can be found in many local galleries, including Grovewood Gallery in Asheville. www.linkwoodworks.com

Distinguished Alumni: Melissa Engler

After working in restaurants for more than 10 years, Engler sees the woodshop as her future. Since

After working in restaurants for more than 10 years, Engler sees the woodshop as her future. Since graduating from the program this spring, she spent much of her summer preparing pieces for entry into the Design Emphasis competition at the International Woodworking Fair, where she won two awards and fellow HCC student Joshua Janis won a third. She’s already sold some of the pieces she made in school during a show at the Folk Art Center in Asheville.

Engler plans to continue working at Asheville

eateries to support herself while her business gains momentum.

m.englerdesigns@yahoo.com