Links to the Past

Links to the Past: From the opening of the state’s first course 130 years ago to the Morganton amateur who almost won the Masters against Ben Hogan, golf has enjoyed a long and fascinating history in these mountains

While Pinehurst is the place most commonly associated with golf in North Carolina, the game was first played in the mountains. The lead up to the first tee shot began in 1888 when the MacRae family of Wilmington and several other investors purchased roughly 16,000 acres in the shadow of Grandfather Mountain with the intention of creating “a popular resort for health and pleasure.” Such an establishment came to be after Professor William James of Harvard University visited in 1891 and soon began construction of the original Eseeola Lodge.

Hugh MacRae decided that Linville also needed a golf course to attract guests, particularly from the Northeast where the game was becoming popular. A rough nine-hole course was carved out in 1895 along the Linville River. The rudimentary layout featured sandboxes where players mounded sand to tee up their balls. Another five holes were added in 1900, and golfers then played four holes twice to get a full round of 18.

Photos from the period show nattily attired players, both men and women, hefting hickory-shaft clubs often before spectators. Gentlemen usually sported ties and stylish hats, while the ladies carried forth in the latest dresses. Commonly accompanying the players were local lads serving as caddies, toting clubs in leather bags.

The growing popularity of Linville as a destination prompted Hugh MacRae’s son, Nelson, to undertake an expansion in 1924 that included a new golf course nearby. A young Scottish architect who was gaining renown for his designs at Pinehurst was chosen to build the new course. The now-legendary Donald Ross spent several days mapping the course’s layout, which was carved out by mules pulling drag pans. It officially opened in 1926 with an exhibition by prominent Scottish-American golfer Tommy Armour. With no major redesigns since it opened, the course still bears the dips and depressions of Ross’ work, lending an historic air of authenticity to Linville Golf Club.

Play continued for a few more years on the original 14-hole course, but it closed in 1934 due to the popularity of the newer course. Today, Linville Golf Club remains one of North Carolina’s top-rated courses and a special place where a stroll on the links truly is a step back in time.

The Long Shot

How Billy Joe Patton—a charismatic, heavy-hitting amateur from Morganton—nearly won the 1954 Masters

To quote bill murray’s crazy groundskeeper character in Caddyshack, it was indeed a “Cinderella story” when a burly, crew-cut amateur came down out of the North Carolina mountains and nearly won the 1954 Masters. Hailing from Morganton, Billy Joe Patton was a fast-swinging swatter who could pound the ball a mile, but was never certain where it would land. The bespectacled lumber salesman, who was 32 at the time, qualified for his first Masters through his status as an alternate on the U.S. Walker Cup team.

Up to that point, Patton’s amateur record was spotty, though he was known around his home course of Mimosa Hills for his slick play when a few bucks were on the line. However, he admitted his nerves often got the best of him in tournaments. But a change of attitude gave him a fresh outlook. “I scored 75s and 78s in tournaments,” said Patton, “but back home playing dollar golf, I’d knock it around 67 and 68, playing free and easy. I decided I would play at Augusta the way I played here, not letting the game get too serious.”

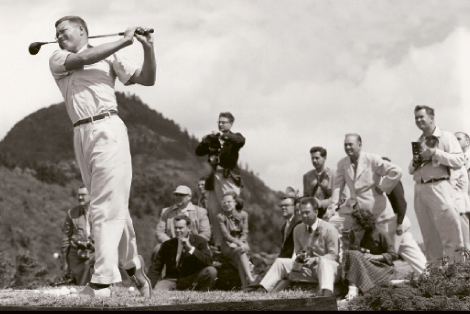

Patton surprised a sterling field with an opening 70 that tied him for the lead, and followed up with a 74 in the second round that kept him one shot ahead of defending Masters champion Ben Hogan. Despite that performance, the smart money was on the amateur to falter even as he became the darling of the gallery with his booming drives and risky assaults on the pin.

Unfortunately, Patton’s wildness punished him in the third round as he posted a 75 that put him five behind leader Hogan and two behind Sam Snead. At that point, the predictions of his slide down the leader board were proving true.

But Patton was still playing with raw abandon and charming the galleries, telling supporters at one point, “You didn’t pay to see me play it safe.” This amateur, declared the Augusta Chronicle, “would charge hell with a bucket of ice water.”

And he charged on Sunday, cheered on by a bunch of friends who had driven from Morganton to watch the action. Patton couldn’t gain ground on the first five holes, but lightning struck on the par-3, 190-yard sixth. “The china started rattling. The walls trembled,” reported legendary player Bobby Jones. “I had to go out on the porch to see what Billy Joe had done now.”

What Patton had done was fly a five-iron straight into the hole. “The ball hit the hole on the fly and wedged between the flagstick and the edge of the cup,” Patton later recalled. “When I took the flagstick out, carefully, there were three times the number of people there as there were when I hit the shot.”

Patton then birdied eight and nine to make the turn at 32. Behind him, Hogan and Snead were having trouble. When he headed into Amen Corner, Patton led the tournament by a single shot. Bolstered by cries of “Go for it, Billy,” disaster struck at the par-five 13th when Patton yanked out his three-wood and went for it. His rapid-fire shot curled right and splashed into Rae’s Creek, a spot that has sunk many players’ hopes. Refusing to concede, Patton pulled off his shoes and socks, and waded in with the intention of blasting out. However, good sense finally prevailed, and Patton took a drop and finished the hole, still barefoot, posting a double-bogey seven that effectively cost him the Masters—though he later claimed it was a bad shot into the pond at the 15th that truly finished him. Pars on the last three holes left him a single stroke out of a Monday playoff, which Snead won.

But his good humor never waned, and as he trudged away from the 15th, he told a glum gallery, “Hey, this is no funeral. Let’s smile again.”

Patton remained an amateur and played in 12 more Masters, posting two more top-10 finishes and taking the low amateur medal five times. But as he later admitted, he does think often about the

Masters he almost won.

The Late Start

Ben Hogan went from good to legendary during a tour through North Carolina

It’s tough to imagine what some sports would be like without their icons: baseball without Babe’s cannon of a swing, basketball without Kareem Abdul-Jabbar’s skyhook, or football minus Joe Namath’s swagger. None of those sports would be the same today. But professional golf could’ve missed one of its biggest heroes if it hadn’t been for a streak of good luck in North Carolina.

Legend has it that in 1940 Ben Hogan was contemplating giving up the PGA Tour and becoming a club pro in Texas. However, a swing through this state provided the springboard for one of the game’s most heralded careers.

Between 1933 and 1951, Asheville was a popular stop for the world’s finest golfers, as it hosted the Land of the Sky Open. Sponsored by the Asheville Civic Sports Association, the tournament was part of the PGA’s winter tour, usually falling in late March just before the Masters. Its list of winners included some of the game’s top names, but perhaps one of the most interesting and important victories was posted by Hogan.

At this point in his pro career, Hogan had played nearly a decade without a victory, earning a reputation as a player who couldn’t close the deal despite his talent. Frustrated by a string of close finishes in early 1940 and running out of money, Hogan arrived in North Carolina doubting his game. But it suddenly clicked. A new MacGregor driver, a gift from fellow Texan Byron Nelson, had Hogan striping the middle of the fairways at the prestigious North and South Championship on Pinehurst’s famed No. 2 course. Combined with pinpoint approaches and a deft short game, Hogan posted his first victory with a record 270 score.

Check in hand, a renewed Hogan headed north for the Greensboro Open where a freak spring snowfall forced a three-day delay in play that had Gene Sarazen joking, “Okay fellas, let’s ski it off.” That didn’t deter Hogan, who putted in his room at the O’Henry Hotel until returning to the course to blitz the field, even with snow still bordering the fairway.

With North Carolina now becoming his favorite place, The Hawk arrived in Asheville where the annual Land of the Sky Open was being compressed into three days because of the snow delays. As usual, the tournament was played at three local courses, with a total purse of $5,000. On Friday, Hogan and nearly 100 other players, including PGA money leader Jimmy Demaret and the entire U.S. Ryder Cup team, met at Asheville Country Club (now the Grove Park Inn’s course). Picking up where he left off earlier in the week, Hogan fired a 67, and then followed up on Saturday at Beaver Lake Golf Course (now Country Club of Asheville) with a 68 that included a back-nine 31. The highlight of the round came when Hogan stunned the large gallery by nearly driving the green on the par-four, 353-yard 16th hole.

Hogan never let up, turning Sunday’s final 36 holes at Biltmore Forest Country Club into what a local sports writer termed a monotonous game of “straight down the middle and dead to the pin,” which resulted in a pair of 69s and his third victory in 10 days.

The normally reserved Hogan, with his $1,200 check in hand, joked during the awards ceremony about the swarms of pesky gnats that the players had battled during the tournament. “You misnamed this tournament, Frank,” the grinning winner told Frank Coxe, head of the Civic Sports Association. “Instead of Land of the Sky, it should be Land of the Fly.”

But Hogan didn’t let a few insects keep him away from Asheville. He returned to win the Land of the Sky Open again in 1941 and ’42, adding to what ultimately would total 64 career wins

Drive a Mile

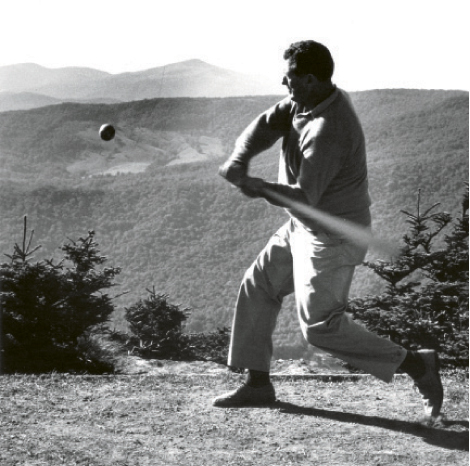

Imagine how great it would feel to whack a ball from the top of Grandfather Mountain

Hitting the ball a mile may seem like the hyperbole of a driver commercial, but at one time, Grandfather Mountain loosely claimed to offer that opportunity. In 1954, shortly after Morganton’s Billy Joe Patton almost won the Masters tournament (see page 64 for the story), promoter extraordinaire Hugh Morton built a tee near the top of Grandfather Mountain that Patton inaugurated by reportedly hitting the ball more than 250 yards out before it fell a thousand feet down into the valley. Billy Joe’s Tee was open to visitors who brought their own clubs and balls to fire away.

“It wasn’t exactly a mile, but it was exhilarating to see your ball seemingly stay in the air forever,” says Harris Prevost, vice president of Grandfather Mountain. “It certainly made you feel like a big hitter.”

The tee remained in use until the late 1980s when it was closed after teenagers decided it was more challenging to try to hit cars in the parking lot several hundred feet below.

Diamond Creek

Best of the West

Score your next round at some of the state’s best mountain courses

Start booking your tee times now for summer, because the North Carolina Golf Panel just released their list of top golf courses in the western part of the state. Most of the courses that made the list are private, so you’ll probably want to take a spin through your Rolodex to find some acquaintances who can invite you for a round.

Best by Region (Western)

1. Grandfather Golf and Country Club, Linville

2. Elk River Club,* Banner Elk

3. Linville Golf Club,** Linville

4. Biltmore Forest Country Club, Asheville

5. Rock Barn Golf and Spa (Jones Course), Conover

6. Wade Hampton Country Club, Cashiers

7. Bright’s Creek Golf Club, Mill Spring

8. Balsam Mountain Preserve, Sylva

9. The Cliffs at Walnut Cove, Arden

10. Diamond Creek Golf Club, Banner Elk

11. Linville Ridge, Linville

12. Lake Toxaway Country Club,** Lake Toxaway

Hidden Gems

1. Hound Ears Club, Boone

2. Mount Mitchell Golf Club,* Burnsville

3. Roaring Gap Club, Roaring Gap

4. Boone Golf Club,* Boone

5. High Meadows Country Club, Roaring Gap

—Rankings courtesy of North Carolina Golf Panel

* Open to public ** Open to lodge guests