Ian Brownlee

Ian Brownlee:

Myths have fueled artists’ imaginations for the better part of human history—from the Egyptian hieroglyphics to the Renaissance revival of classical philosophy and religion. While folklore and creation stories have universal appeal, they provide more specific insight for artist Ian Brownlee. “Mythology lays out people’s assumptions about themselves and the world,” he says.

Many of Brownlee’s paintings in the collection American Myths are based on old photographs, chosen as starting points for allusions to bigger stories.

Children dressed in archaic fashions, farm boys posing on the back of a cow, and synchronized dance troupes are woven into fantastical narratives under his brush. For the wiry and serene 32-year-old from Augusta, Georgia, the subjects of his paintings take on life outside the frames he finds them in. “I came across a picture of these kids dressed up for a parade in really ornate costumes. They were just dressed that way for a day, but in my mind, that’s the way these kids always dress,” Brownlee says. “They’re from a culture like ours, but only slightly different.”

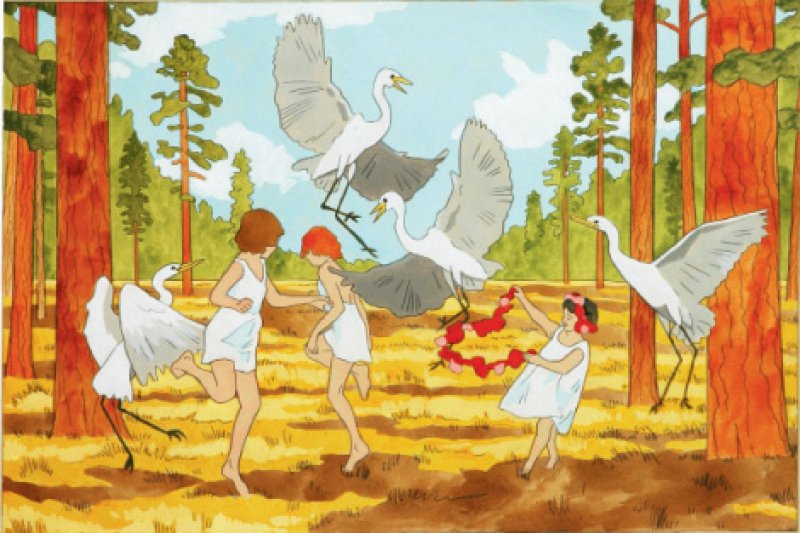

A full-time painter at Minerva gallery in Asheville—he also created the pastoral mural at Rosetta’s Kitchen—Brownlee spends a fair amount of time focusing on natural beauty. But landscapes play a supporting role in this body of work, adding meaning to repeated motifs of children, music, rituals, and anthropomorphic birds, whales, and foxes. The content ranges from playful to subversive. In the world of American Myths, boys take thousand-mile journeys through mountain ranges, cranes witness a child’s baptism in black swamp water, and foxes lead (or possibly lure) dance lines of young girls through the woods.

Brownlee’s humor is present in each, but so is the hint of danger. In most myths, he explains, “there’s something kind of magical and something kind of scary. They’re dream-like and don’t always make sense.” And while humans have used myths to make sense of the unexplainable, Brownlee leaves his stories open to interpretation. “If you look at it and you can see the whole story, then you’re finished. That’s it,” Brownlee says. “I want the mind to make up the rest.”