One Year Later: Reflecting on Hurricane Helene, the storm that shaped WNC's landscape

One Year Later: Reflecting on Hurricane Helene, the storm that shaped WNC's landscape: The recovery of Asheville, Spruce Pine, and Old Fort

Spencer Bost stood between two rail lines, a Red Bull can clutched in his fist, staring down Locust Street, known locally as Lower Street, in Spruce Pine’s historic downtown. “I miss the trains,” says Bost, the twenty-seven year-old director of the non-profit Downtown Spruce Pine. Not the roar of locomotives and clattering of coal brimmed gondolas, but for what they represented: the rhythm, routine, and the steady pulse of the small mountain town.

Spencer Bost, executive director of Downtown Spruce Pine, stands on the railroad lines damaged during Helene.

The red-bearded Bost explained that when the North Toe River in Mitchell County surged to a record flood stage, more than twenty shops and restaurants were gutted and CSX Corporation’s Blue Ridge Subdivision rail line suffered extensive damage, requiring months of repairs. Now with a handful of storefronts reopened, Bost and his neighbors are working to resurrect the town’s spirit before autumn visitors return.

Hurricane Helene didn’t just twist miles of iron rail, flood storefronts and homes, and wash out roads, it knocked the wind out of a region’s economic revival. In Spruce Pine, Old Fort, and Asheville’s River Arts District, Helene left behind a reckoning: How do the economic, cultural, and artistic hubs of mountain communities rebuild after catastrophe while holding on to the soul that made them special?

SMALL TOWN CHARM

Spruce Pine, Bost says, owes its existence to the railroad.

Downtown Spruce Pine (left) lost many businesses in the flood, but many, like Treasure in the Pines (right), Rocks & Things, and Live Oak Gastropub have since rebuilt and reopened.

The line is a legacy of the town’s 150-year-old mining industry extracting quartz, mica and feldspar from among the richest ore deposits on the planet. “We like to joke here that everyone has a little bit of Spruce Pine in their pocket,” Bost says while patting his own mobile device whose screen sparkled from the minerals embedded within it.

Now, however, tourism is a key driver in the future economic stability of Spruce Pine and dozens of other communities throughout the region. Thousands of jobs rely directly or indirectly on access to public lands, crafts, and outdoor recreation. Before Helene, 11.5 million visited the mountains each year, bringing $7.7 billion to the local economy.

Of course, what makes Spruce Pine extra special and worthy of a visit is its small town charm, the proximity to the region’s highest mountains, and the Southern Appalachian craft heritage. Mitchell County, he says, is framed by outdoor recreation; the northern border is the Appalachian Trail and the southern boundary is the Blue Ridge Parkway, among which many sections remain closed due to storm damage. “We have this fun blend of authentic Appalachia, world class art and our natural beauty and trout streams,” he says.

The Southern Appalachian mountains, however, are especially vulnerable to flash flooding, a hazard elevated by what forms their raw beauty: steep slopes and high peaks. Rainfall from Hurricane Helene intensified as moist air from the Gulf of Mexico climbed the high ridges of the Blue Ridge, cooling and condensing rapidly, a phenomenon known as orographic lift. So when Helene parked itself over the region’s lofty peaks, rainfall cascaded down them as if water wrung from a soaked sponge lifted from a bucket. Spruce Pine, cupped in a river valley at the confluence of runoff from three of the region’s tallest mountains—Roan Mountain, Grandfather Mountain, and Mount Mitchell—took the brunt of it.

In the days after the storm, Cheryl Buchanan stood on Lower Street in a pink T-shirt and black ball cap, taking in the wreckage. She owns Treasures in the Pines, a bustling emporium that supports more than 60 consignors, who are local artists, antique dealers, and sellers of knick-knacks. She’d planned a five-year anniversary celebration on October 9, 2024. Instead, she spent the day emptying her shop, where most of the merchandise was ruined.

“It’s too soon to tell,” she told me last October, when asked if she would reopen.

But by the following July, after a brief relocation to Upper Street, Treasures in the Pines reopened several storefronts from its previous location, among the first businesses back and a hopeful sign.

TOWN & COUNTRY

Old Fort, a former railroad and mill town 45 minutes down the road in McDowell County, faced a different but equally daunting challenge.

Next to the Old Fort Train Depot is the Arrowhead Monument (right), a 14.5-foot statue made from pink granite that was designed to recognize the peace treaty between the indigenous Cherokee and Catawba people. After Helene, many important areas of Old Fort were damaged, like the G5 Trail Collective (left).

When Helene hit, it pounded the Pisgah National Forest, toppling scores of trees and unleashing dozens of landslides. The resulting runoff surged into Mill Creek, transforming the typically tranquil stream which flows through downtown Old Fort into a raging torrent funneling loads of debris downstream. Tangles of uprooted trees and household wreckage jammed the stream as flood water surged over its banks flowing into homes and businesses, including Chad Schoenauer’s cycle shop.

Chad Schoenauer (left), owner of Old Fort Bike Shop (middle), lost a lot of inventory because of the flooding that reached the downtown area. One of Old Fort’s biggest draws for visitors is its extensive mountain biking trails (above), some of which were also affected by the storm.

Schoenauer, a journeyman bike mechanic and manager, opened the Old Fort Bike Shop in 2021, inspired by ambitious plans for a new trail network in the national forest. His shop flooded with three feet of water and was buried beneath an eight-inch layer of mud. Much of his inventory was destroyed.

The future of Old Fort, like so many towns in the region, isn’t looking backwards. Over a century ago, the town was dependent on saw mills and tanneries that relied on the bounty of massive American chestnuts, hickories and oaks that covered the slopes. Today, however, Old Fort’s economic prospects don’t hinge on the volatile boom and bust cycle of manufacturing or timber.

Instead, the fortunes of Old Fort’s 1,000 residents may be linked to potential opportunities associated with 42 miles of new recreational trails in the Grandfather Ranger District of the Pisgah National Forest. In 2019 Jason McDougald, the executive director of Camp Grier at the edge of Old Fort, is also a leader of the nonprofit G5 Trail Collective realized there was untapped potential for trail development in the tens of thousands of acres of national forest sandwiched between Old Fort and the Blue Ridge Parkway. Since 2021, according to McDougald, 20 businesses have opened in Old Fort. The economic engine that’s driving the growth: visits to the Pisgah National Forest.

Camp Grier’s executive director Jason McDougald and Lisa Jennings with the US Forest Service (right). Hillman Beer brewery (bottom-left) sits right along the river (top-left) in downtown Old Fort.

“We are special in that we are the first round of major trails in the mountains, from the east, along the I-40 corridor entering Western North Carolina,” says Schoenauer. Roughly 80 percent of his customers are riders from Asheville, Raleigh, and Charlotte. Before Helene, business was growing by 30 percent annually, sustained by mountain bikers visiting Old Fort for rides on legendary trails such as Kitsuma, the Gateway Trails complex, and Heartbreak Ridge trail.

“The trails and outdoor economy here are directly tied to G5’s progress,” Schoenauer says. “I believe in Old Fort; we’re adapting quickly.”

His resilience mirrors the community’s. Within months, US Forest Service crews and volunteers reopened eight miles of trails. More remain closed, but visitation is slowly rebounding. The Old Fort Bike Shop’s century-old building has a smooth new concrete floor and is jammed with sleek new cycles. A sign in his shop summed up his attitude: “Come hell or high water”.

“I’ll be sticking it out,” he claims. “I’m not going anywhere.”

HOME OF THE ARTS

Along Asheville’s river side, Helene upended what seemed like an unstoppable trajectory of two decades of growth and hardy economic development. The French Broad River tore through the River Arts District, a collection of neighborhoods, parklands, and commercial areas ravaged by floodwaters.

The River Arts District (top-right) is directly next to one of Western North Carolina’s major waterways, the French Broad. Floodwaters rose unimaginably high, destroying buildings and businesses, streets, and possessions.

The French Broad riverside was once described as a “trash heap” of decaying factories and warehouses. Industries began shuttering there in the 1940s, plagued by chronic floods. Passenger rail service stopped in the 1960s. By the 1980s, the area was derelict, a tangle of weeds, broken windows, and rusting steel.

“When they stopped passenger rail service this place went into a really bad, bad place,” says Steph Monson Dahl, the City of Asheville’s chief urban planner. “The railroad was one of the largest employers and all of the barber shops, lunch counters, and hotels that sprang up around it disappeared.” Urban renewal projects further displaced the once-thriving historically Black neighborhood and what was left were the rotting structures, many of them vacant for decades.

In the late 1980s, a trickle of artists began moving into the neglected riverfront, lured by inexpensive studio space and the gritty charm of its decaying industrial buildings. In 1989, a collaborative design process, known as a charette, produced the Asheville Riverfront Plan, an aspirational blueprint that reimagined the area as a thriving center for art, culture, and outdoor recreation. Five years later, artist Pattiy Torno organized the district’s first studio walking tour, setting the stage for an artistic revival that would help reshape the identity of the once-neglected riverfront.

Dahl began work with the city in 2005 and helped implement the Wilma Dykeman RiverWay Master Plan, establishing new greenways and parks. Over the next two decades, the River Arts District evolved from a blighted landscape to one of Asheville’s liveliest destinations, with galleries, studios, breweries, hotels, restaurants, and parkland along the river.Helene upended that progress.

Floodwaters surged through the district, destroying studios, greenways, and businesses, including the Wrong Way River Lodge & Cabins. Owners Joe Balcken and Shelton Steele opened the riverside campground with 13 elevated cabins in 2022. Though their damage was significant, it was manageable. Once the floodwaters receded, Balcken turned his attention downstream to support others facing stunning losses.

“We recovered pretty quickly. I was able to pick my head up and ask, ‘how can I help?’ This felt like a chance to start shaping a bigger vision,” Balcken says.

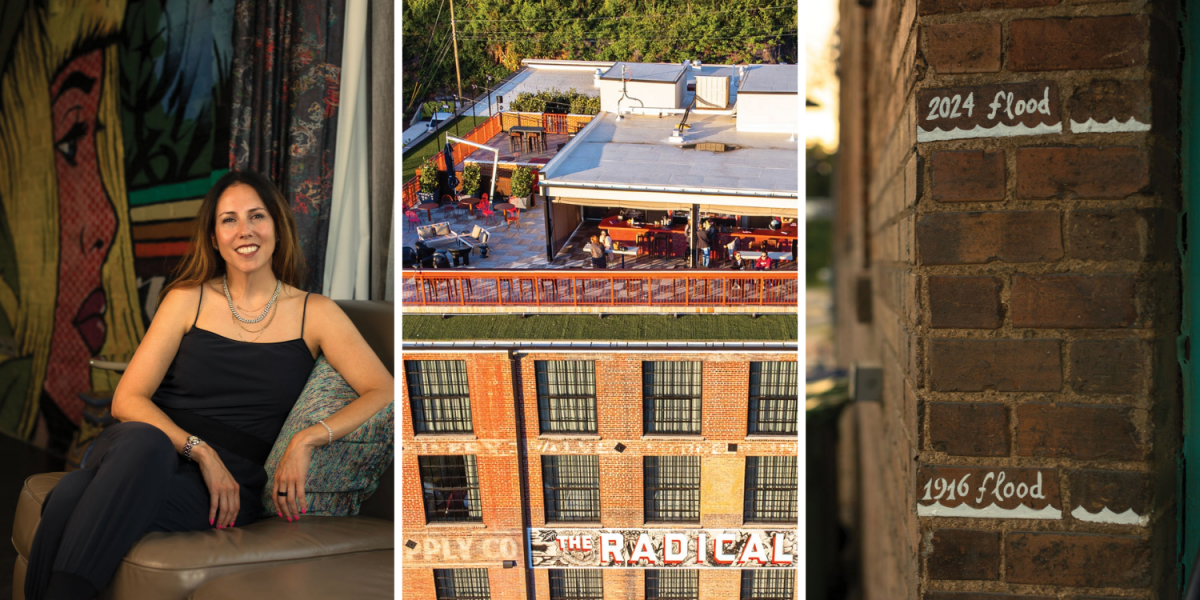

He teamed up with local leaders, such as Dahl, jewelry designer Jeffrey Burroughs, and Amy Michaelson Kelly, owner of the Radical Hotel in a former mill building and the restored Phil Mechanic Studios, to form Unified RAD, a coalition of artists, property owners, business operators, and residents who organized short, medium, and long-term recovery committees.

Amy Kelly (left) is the owner of The Radical (middle), an artsy boutique hotel that opened one year prior to Helene. The RiverLink office in the RAD marks the height difference between the historic flooding in 1916 and Helene (right).

“Together, we’re much more capable than we are individually, because it is so overwhelming,” Kelly says. Their efforts include reviving the RAD Round Table, a monthly gathering open to anyone to address challenges and visioning around storm recovery.

In the process, Balcken connected with Lisa Raleigh, executive director of RiverLink, a nonprofit focused on environmental and economic stewardship of the French Broad watershed. Together they funded a new community design charette aimed at identifying “catalyst projects” to build a sustainable artistic and ecological future for the River Arts District that balances the creative economy, river health, and the diversity of visitors and businesses the district relies on.

“Getting everyone to the table is essential,” Balcken said. “We need a comprehensive plan that serves artists, residents, the river, and our local economy.”

For Raleigh, the region’s future resilience also depends on restoring its fragile streambanks. “The amount of damage is biblical,” she says. “Without a stable riparian zone, we’re hyper-vulnerable to floods.” Raleigh emphasizes that restoring and protecting streambanks must be a priority in every conversation about the next phase of redevelopment in the River Arts District.

Their work complements efforts by Dahl and D. Tyrell McGirt, Asheville’s Parks and Recreation director, who is leading a parallel initiative to repair parks and greenways. “These are our most active spaces in our city. We want to take advantage of the opportunities that we’re seeing as a result of this storm to do something new and special in those areas,” McGirt says. “We’re committed to the long term recovery process.”

D. Tyrell McGirt and Steph Monson Dahl photographed in the River Arts District (right). The French Broad River (left) runs parallel to the area, which made it more susceptible to flooding.

A likely outcome, Dahl predicts, is a greener, less densely built floodplain. “The retreat from the river has been slow, but steady,” she says. “It won’t happen all at once, but you’ll see a place that makes room for the river and the people who love it.”

Balcken and Kelly recognize their role as stewards and torch bearers of a storied part of Asheville’s past and a reason for its attraction to visitors.

“The purpose of Unified RAD was to get as many people as were capable and available emotionally and logistically to the table,” Kelly says. “I think everybody is focused on retaining that creative component that wouldn’t exist without people like Pattiy Torno. I have so much respect for the work and passion she and others have put into creating the vision that we’re benefiting from and we’re very invested in not losing it.”

Many art galleries have reopened, like Wedge Studios (left), but some operations are still recovering, like the Marquee, an iconic art market that is now home to Hendersonville's Wireman sculpture (right).

Dahl embraces the infusion of fresh voices and leadership. “The influx of new energy and amazing humans pushing a shared vision forward means the RAD is in good hands,” Dahl says.

Spruce Pine, too, is betting on its future. Recently, while swimming in a favorite river hole on the North Toe, Bost spotted an Eastern hellbender, a giant salamander considered an indicator species for clean, healthy rivers.

“It’s a good sign,” he says.

During Labor Day weekend, Spruce Pine hosted the town’s first-ever North Carolina Hellbender Festival, celebrating local crafts, native creatures, traditional string music, food, and the community itself. It’s a symbolic step toward recovery, and a reminder of what’s possible when mountain towns refuse to let disaster define them.

“The hellbender is this ancient creature adapting to a new reality in an altered environment,” Bost says. “It survived a one-thousand-year flood. And so will we.”

OTHER LOCATIONS HEAVILY IMPACTED BY HELENE

Helene aftermath in Swannanoa.

Hot Springs: In the mountain hamlet of Hot Springs in Madison County there’s a deep-rooted attachment to this stunning river town. Some downtown businesses have reopened, but many are still working to rebuild following flooding. The town’s economy depends on tourism, among them the steady flow of Appalachian Trail hikers passing through.

Swannanoa: One of the hardest-hit watersheds was in Swannanoa, an unincorporated rural and suburban community in Buncombe County. The Swannanoa River broke a new flood record at the height of Helene when the river crested at 26.1 feet, surpassing the previous mark in 1916 by more than five feet. The non-profit organization RiverLink is currently working in partnership with several groups to evaluate a 6-mile portion of the Swannanoa River and identify future solutions to flooding.

Yancey and Mitchell County Communities: Many small rural communities were deeply affected by Helene, such as Micaville, Cane River, Egypt Ramseytown, and Little Creek in Mitchell and Yancey Counties. In mountainous terrain, people settled near creeks and streams for flat-land to build and raise food. Bakersville-based Rebuilding Hollers Foundation is supporting families in the two counties by providing construction materials and know-how.

The Blue Ridge Parkway: Along the 469-miles Blue Ridge Parkway maintenance crews have restored much of the damage, but some sections of the road way, campsites and visitor centers remain closed. Check the National Park Service’s Blue Ridge Parkway website for updates and consider detours through the region’s charming small towns.