Hidden in Hiddenite

Hidden in Hiddenite: Get to know North Carolina’s rare native emeralds

Walking their freshly-ploughed fields after rain and searching for arrowheads to sell to tourists, farmers in Alexander County’s foothills occasionally came across tiny crystals of quartz and other sparkling minerals. Some of the crystals glowed faintly green, colored like new leaves of spring. Those were emeralds, a gem 20 times rarer than diamonds and occurring naturally in rocks of the Western North Carolina mountains.

Emerald was designated North Carolina’s official state gemstone in 1973. And at a few mines in Hiddenite, Spruce Pine, and Little Switzerland, guests can prospect for emeralds for a small fee and keep whatever they find.

Two basic varieties of emerald crystals are found in North Carolina. In the area around Little Switzerland and Spruce Pine, most emeralds are primarily composed of the mineral beryl. Emeralds found near Hiddenite, a very small hamlet in Alexander County northeast of Hickory, are usually a form of spodumene that exists nowhere else in the world. Emeralds of beryl also occur in the rocks around Hiddenite. The town is named for William E. Hidden, the geologist who discovered the green variant of spodumene in 1879.

Emeralds of beryl and hiddenite are both infused with chromium, which gives them their green color. Those of hiddenite tend to be a bit cloudy while those of beryl are much clearer, harder, and easier to cut into beautifully faceted gems for jewelry.

Hiddenite and beryl are products of very unusual geology underlying isolated areas of Western North Carolina’s mountains. Some 600 million years ago, thick streams of molten minerals with the consistency of hot taffy welled up on convection currents from deep within the earth’s mantle. The force of the current injected these molten minerals into fractures and voids in gneiss, bedrock rock underlying emerald mines.

As the mineral-rich stream cooled ever so slowly, crystals of quartz, mica, beryl and hiddenite grew bigger and bigger. Eons of rain, a weak acid, have dissolved emerald-bearing bedrock into saprolite, a reddish orange clay-rich dirt in which mica, quartz, beryl, and hiddenite is left untouched.

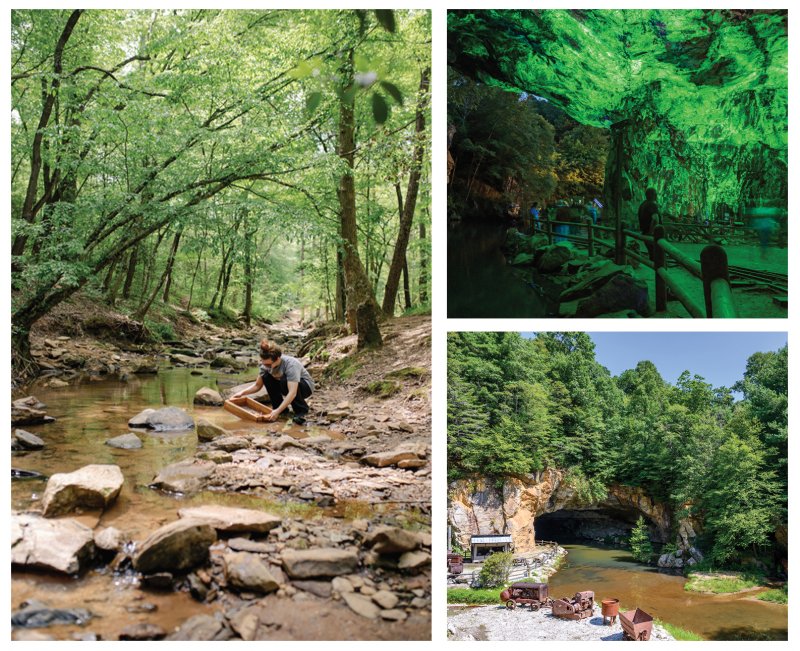

(Left) When digging on the property, Chipman makes his way through saprolite in order to find interesting rocks and gems; While some of Hiddenite’s emeralds have been larger than your hand, a majority are about the size of a quarter (above, right).

FROM WHENCE COMETH THE QUEEN

For generations, a tract of about 100 acres near the hamlet of Hiddenite has yielded hundreds of emeralds. While owned and operated as the North American Emerald Mine, its owner, James K. Hill, found a rough emerald of 71 carats. Cut into a beautifully faceted gem weighing 18.8 carats and named the Carolina Queen, it is known worldwide as the largest and finest emerald ever found in North America. Her consort, the 7.8-carat Carolina Prince, was cut from the same rough green crystal.

Five years later Hill dug up a 1,861.9-carat behemoth.

At that time, Hill was the latest in a string of owners of the mineral-rich acreage dating back to the late 1870s. In those days, Thomas Edison was searching for platinum to use as filaments in his electric lights. Word that Western North Carolina’s farmers had been collecting gems—emeralds, aquamarines, rubies, sapphires, garnets, topaz, and amethysts—filtered its way to Edison’s labs in New Jersey.

Thinking that platinum ores might be associated with gems found in Western North Carolina, in 1879 Edison dispatched geologist Hidden to meet gemologist J. A. D. Stephenson and explore the region. In a bit of supreme irony, Hidden had learned his mineralogy by attending public lectures from a geologist named Stone.

During his investigations in Alexander County, Hidden had discovered a crystalline rock colored green like emerald. From its shape, lacking classic six-sided structure and being softer, he knew it was not a form of beryl. He sent the stone to famed mineralogist J. Lawrence Smith, who was highly respected in the nineteenth century for his research on the composition of meteorites. Smith determined the rock was an unknown form of spodumene.

Because of the unique combination of lithium, aluminum, and silica in the sample delivered by Hidden, Smith named the new mineral “hiddenite.” Hiddenite can vary in color from emerald green to pink and lilac, a gem known as kunzite. Emerald-colored hiddenite, because of its more fragile crystalline structure, is more difficult to cut. Therefore fine gems fashioned from hiddenite may be worth more than those of beryl.

FINDERS KEEPERS

Mike Watkins purchased the land across the creek from Hill’s operation and opened Emerald Hollow Mine to the public in 1986. A trained geologist, during his career Watkins traveled to South America, India, Pakistan, and Afghanistan searching for deposits of beryllium, the defining mineral in beryl. Alloyed with steel, beryllium was essential in making armor for tanks and other military vehicles. The mine is currently owned by Jason Martin and Dottie Watkins.

Emerald Hollow is one of the only mines where the public can actually dig for emeralds—and keep what they find—where they occur naturally. According to Watkins, hiddenite is only found in a vertical vein of rock roughly three miles long and one mile wide, right near Emerald Hollow Mine.

But despite its small size, this land holds over 60 different types of naturally occurring gems and minerals including amethysts, sapphires, and aquamarines. Notably, Emerald Hollow Mine is also home to exceptionally clear and smoky crystals, which many cultures believe have healing properties.

Mine visitors tote their shovel and five-gallon bucket down along a winding gravel road down to the bank of exposed saprolite. Either Tommy Chipman, operations manager for the mine, or one of his guides, will show them where gems have been found previously.

“It’s a lot of hard work, but it’s very rewarding in the end to see something that you were the first person to dig out of the ground,” said Chipman. He has helped many visitors locate and dig up emeralds, crystals, and other stones over the years.

Digging for gems is difficult—four or five shovelfuls load the bucket with enough dirt to tote up the gravel road 125 yards to the sluice trough. In water running down the trough, miners wash handfuls of dirt in screen-bottomed boxes hoping that among the remaining flecks of mica and quartz they’ll find an emerald. For those not inclined to put foot to shovel and dig deeply into saprolite for gems, sediments in two creeks offer an easier opportunity. Every downpour washes fresh sands and gravels into the streams. Armed with a screen-bottomed sluice box, one can wash away mud, leaving small crystals.

And, like many so-called gem mines lining tourist routes near Franklin, Brevard, Waynesville and other mountain towns, visitors can purchase buckets of dirt from the mine to wash that have been “enriched” (miners call this “salted”) with mineral crystals collected elsewhere. The more one pays per bucket, the bigger the crystals they’ll find. Regardless of price, some will contain emeralds.

Fine jewelry, cut and designed from the gemstones found on the property, can be handcrafted by Mike, the mine’s head gem cutter. Lapidary services are becoming more difficult to come by, especially on the East Coast, due to the high costs and specialized knowledge needed to cut gemstones effectively. From pendants and rings to bracelets, cufflinks, and tie tacks, Emerald Hollow Mine not only produces rare gemstones but showcases them. The shop also offers gems, literature, and related material for sale.

Gemstones are added to the buckets to enrich the mining experience.

NEXTDOOR NEIGHBORS

Near Little Switzerland lies the North Carolina Mining Museum at Emerald Village, the latter being a notable representation of commercial mining and milling of minerals. The major industry has sustained much of the region here since the 1880s. The village contains five mines in the Spruce Pine pegmatite, once molten geologic material rich in gemstones similar to the vein underlying Hiddenite.

At one of Emerald Village mines, Crabtree, on a hot July day in 1979, Audrey Lineberger found the gem of a lifetime: a 1,492 carat emerald. Audrey was a professional psychic, writes Robert J. “Bob” Schabilion, founder of Emerald Village, in his book, Down The Crabtree. When her son was beset with a serious illness she made a pact with God, that if he would help her find “a rock I could sell for $20,000 . . . I’d go out in the world and help others if he would let my son live.”

“She paid her $4 fee like everyone else . . . and told me she was going to find the largest emerald ever to come from this mine,” said Bill Collins, co-owner of the mine, who told her to wait for the next mining car to come to the tracks. “She walked over to the track and stood patiently until the car load of rocks from inside the mine had been dumped along the track, as was the custom. She reached down and picked up a large rock, quietly looked at it and said ‘Thank you Lord . . . ’ It was a single emerald crystal about 1 1/4 in diameter.

Bon Ami is the name of another mine in Emerald Village. The name may ring a bell. Bon Ami is a popular kitchen and bathroom cleaning powder and paste. Valued for its very fine abrasive quality, silica derived from the mine’s feldspar was a principal scrubbing ingredient in the cleaning agent.

One of five historic commercial mines now closed in the village, the Bon Ami mine is open for tours. When deep underground, guides will turn off lighting along the path. After a few minutes to let visitors absorb total darkness, guides will turn on “black lights, illuminating the walls and crystals embedded in the rock glow in stunning fluorescent yellows, blues, greens, and reds.

Beautifully curated by second-generation owners Alan and Cathy Schabilion and their family, the Emerald Village offers guests the opportunity to tour a huge hard-rock feldspar mine and the mill where ore was processed from the 1920s into the 1950s.

The mill contains extensive displays of mineral crystals from the mine, as well as carbide headlamps and other personal equipment used by miners. Machinery to extract ore from the mine, haul it to the mill, and crush it is displayed outside the building. Visitors also have the opportunity to hunt for emeralds on the property.

RESOURCES

Emerald Hollow Mine

484 Emerald Hollow Mine Dr., Hiddenite

Open daily 8:30 a.m.-sunset, closed Thanksgiving, Christmas Eve, and Christmas Day

(828) 635-1126; emeraldhollowmine.com

Emerald Village

331 McKinney Mine Rd., Spruce Pine

Open April-November, 10 a.m.-5 p.m. daily, 9 a.m.-6 p.m. daily from Memorial Day weekend through Labor Day weekend

(828) 765-6463; emeraldvillage.com