Last Stand

Last Stand: Remembering the Battle of Asheville on its 160th anniversary

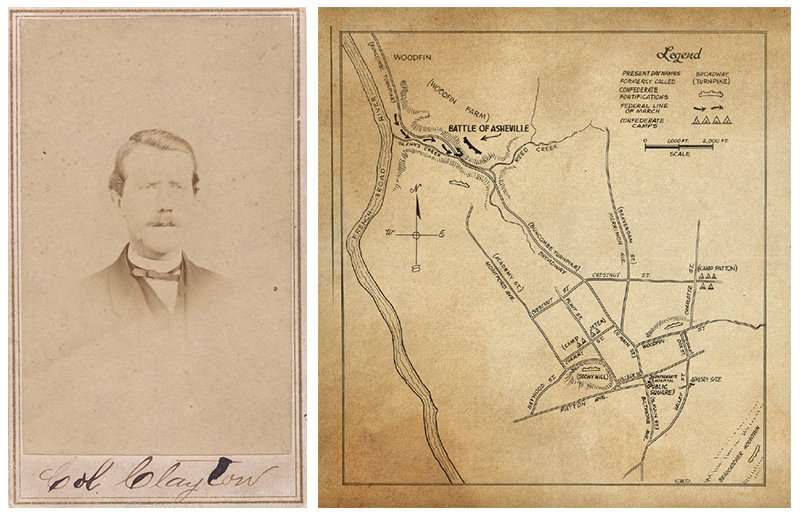

The Battle of Asheville took place in the northern part of town.

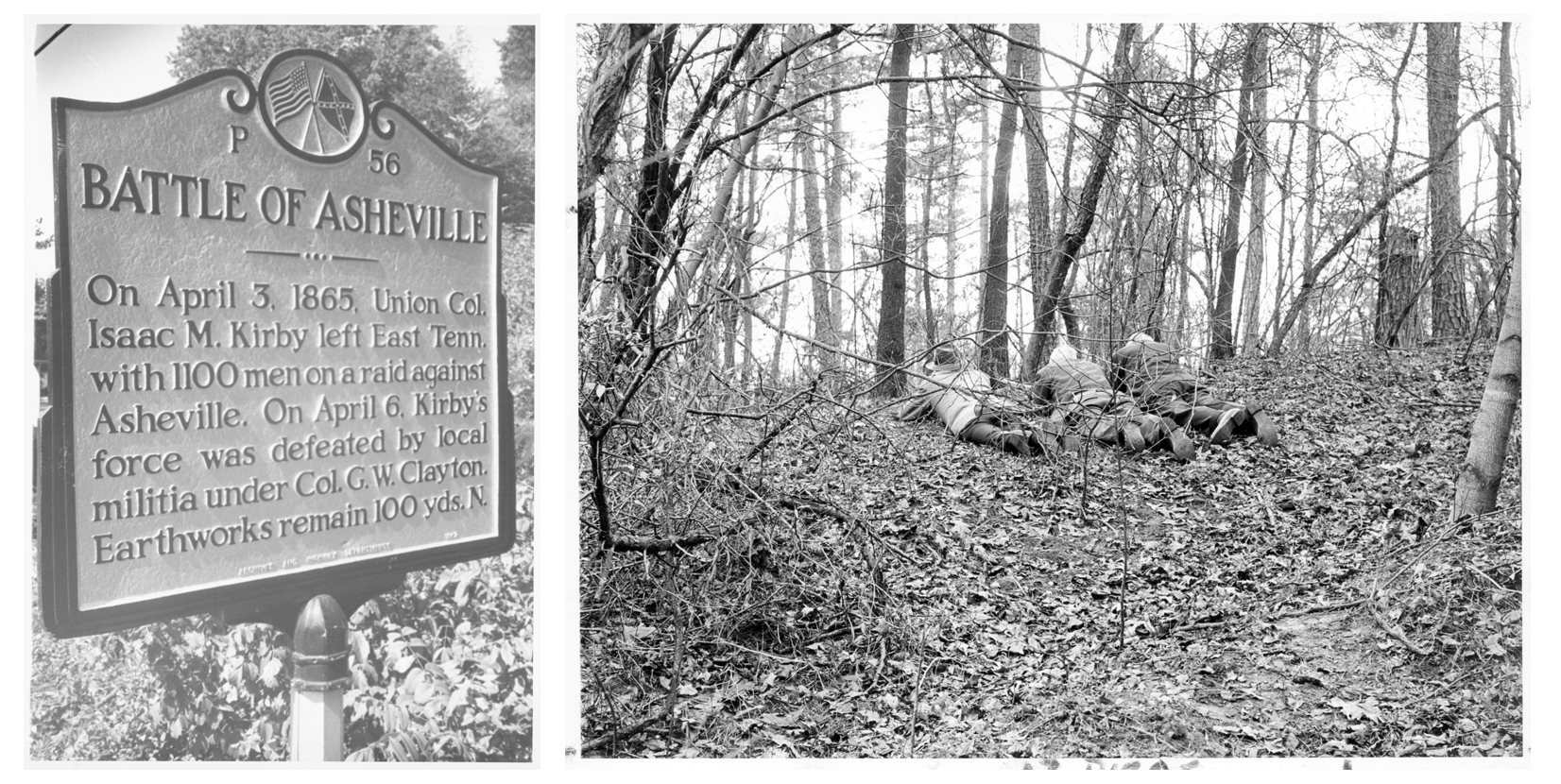

Visitors strolling the 10 acres of Asheville Botanical Garden next to UNC Asheville this April will encounter blooms of trillium, foamflower, and crested dwarf iris, all emerging from a fresh tapestry of springtime green. They will be hard-pressed to imagine that on these tranquil grounds an armed conflict once raged—that the air was choked with smoke and war cries, that cannon volleys tore through trees and earth, and that here took place one of the closing chapters of the country’s greatest internal bloodletting.

Call it the Battle of Asheville, as many do today. In its time, though—the waning days of the Civil War—few would have called it that, so brief was the action and so limited the consequences (a few wounded and no deaths). Call it a skirmish, a clash, a standoff, or “a game of bluff,” as one writer put it. By whatever name, it was a brief but significant milestone in Asheville’s Civil War saga.

In the early days of April 1865, the war was still fierce on some fronts but was largely winding down. In Western North Carolina, Union Army raiders made incursions from several directions toward Asheville, which had hosted a Confederate rifle armory during the early years of the war and was now home to some 1,100 white residents and 750 enslaved people. A couple hundred of the men, many of them senior citizens or convalescing wounded, served as the Silver Grays—a home guard in the event the town required defense.

Historians visited the former Woodfin Farm to reenact the brief wartime conflict.

From eastern Tennessee, 900 Union infantry under the command of Col. Isaac Kirby were dispatched to scout and potentially take Asheville—so long as doing so would incur no loss of life. The war was so close to ending, federal generals reasoned, there was no purpose in bloody combat with the mountain town’s Confederate holdouts.

By the time Kirby’s men reached the outskirts of Asheville on April 6, at what was then known as Woodfin Farm, the Silver Grays and other locals, commanded by Col. George Clayton, had rallied to rebuff them. With two or three small cannons and a few score rifles, the ragtag Confederate force perched on two small ridges and blasted away. From a relatively safe distance below, Kirby’s soldiers responded in kind for the better part of the afternoon. But as dusk approached, a spring rain turned downpour, and the Union force decided to call it a day.

Kirby’s troops withdrew, but within weeks, Asheville’s Confederates would capitulate without another shot as part of formal surrender arrangements. Call it what you will, the Battle of Asheville proved a short-lived victory.