The French Broad Old River, New Current

The French Broad Old River, New Current: Western North Carolina’s iconic watershed continues its journey of preservation and growth into the future

Cross any of the bridges over the French Broad upstream from Marshall on a reasonably warm weekend day. Whether you look upriver or down, you will see flotillas of happy folks riding brightly colored inner tubes and stand-up paddle-boarders weaving in and out.

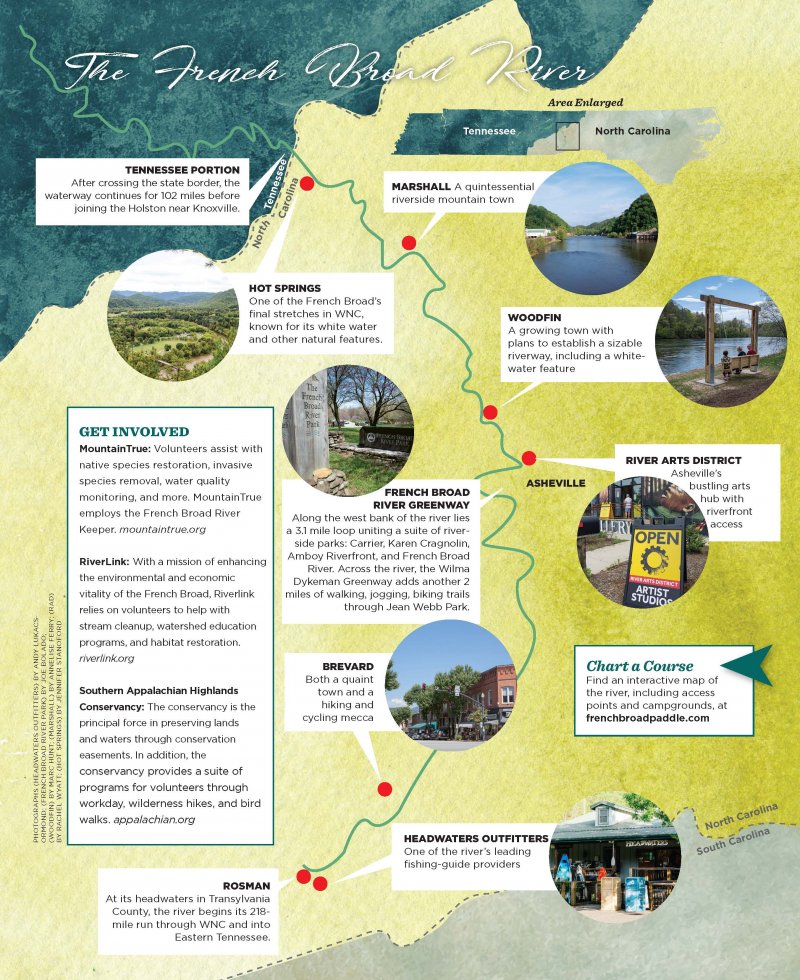

To float the French Broad from its headwaters south of Rosman to Newport, TN, to paddle the length of TVA’s Douglas Lake, and to let the river’s current carry you south to Knoxville, is to ride through some 300 million years of history. From across the gunnels of your canoe or the coaming of your kayak’s cockpit, much of Western North Carolina’s and East Tennessee’s history will stare you in your face.

Let’s get the river’s age out of the way right now. Is it the second oldest, the third oldest or the sixth oldest in the world? Nobody knows for sure. And its age doesn’t make any difference anyway. Let’s just say that it’s one of the world’s oldest rivers.

How do we know? The French Broad started eroding its way down through the Blue Ridge Mountains as they were first being uplifted around 300 million years ago. According to Bob Hatcher, the retired UT-Knoxville geologist who spent 40 years studying the evolution of the Southern Appalachians, the mountains we see every day are somewhere between 25 and 50 million years old. They are at least the third and maybe the seventh range of mountains to occupy this place on the earth’s crust.

Earlier ranges were pushed up and eroded down to terrain like the Piedmont, pushed up and eroded down, and pushed up and eroded down again by the same geologic and climatic forces at work today. Climate, we experience every day. Every year or so a slight tremor rattles the dishes in our kitchen cabinets. Those tiny earthquakes remind us that the mountains that look so stable and permanent are still moving.

From Rosman to Newport, the French Broad shows us three personalities. From its headwaters to Asheville, the river winds languidly through bottomlands and drops about three feet per mile. Now farmed to provide produce for area grocery stores, from the late Woodland era 3,000 years ago until the 1830s, Cherokee and their ancestors grew squash, corn, and beans here on small plots of an acre or two.

As you float the upper section you will glide by several fish traps, submerged weirs of boulders projecting from each bank and pointed like a “V” downstream. Upstream of the “V,” Cherokee would run downstream flailing the waters chasing fish to others waiting with baskets where the weirs came closest together.

At Horseshoe Bend, a big loop in the river crossed by US 64 between Brevard and Hendersonville, Sidney Vance Pickens launched his scheme to create a steamboat line all the way to Knoxville. With great fanfare in 1881 his side-wheeler, Mountain Lily, left its dock but made it only a few miles downstream before running aground. Pickens’ folly never sailed more than three or four miles and was ultimately wrecked in the flood of 1885.

Just upstream from Asheville, the French Broad picks up speed and begins to drop 12 feet per mile. For the next 55 miles to Hot Springs, the river is paradise for whitewater fans. When weather warms, laughing tubers ride riffles from Long Shoals to Silver-Line Park at Woodfin. Below Craggy Dam, water velocity picks up. Kayakers and canoers find the 30-mile run from Ledges Whitewater Park to Hot Springs delightfully challenging. The section ends below Frank Bell’s Rapids rated class III-IV.

From Hot Springs to Newport, the river resumes its riffle-run character. Eight miles below Hot Springs, a cliff known as Paint Rock rises on the north side of the river. On the face of the cliff 5,000 years ago, people of the Archaic era painted petroglyphs in orange and blue. Archaeologists surmise that the rock art directed travelers to the warm springs up the river. Picture people of so long ago soaking in the warm springs to ease their aches just as hundreds do today at Hot Springs Resort & Spa.

All in all, the French Broad is a monument to our land’s history and culture, past and present. However, for more than 50 years—albeit, merely seconds against the river’s lifespan—the watershed was used as a dumping ground for runoff waste and trash. But through the efforts of impassioned individuals and organizations, the waterway has undergone a dramatic transformation in the name of protection and conservation. In the last few years, more work has been done to improve the water’s quality, leading to environmental and economic benefits. And the leaders of the French Broad movement have quite a future planned for the river—and the community.

Paddle the river’s bucolic reaches and see the river as ancestors of the Cherokee knew it 2000 years ago.

How Safe Is the Water?

In 2022, North Carolina’s Department of Environmental Quality listed the 19 miles of the French Broad from Long Shoals to Craggy Dam as “Impaired” according to water quality standards set by the federal Clean Water Act. Water quality monitoring was recording increased levels of E. coli and fecal coliform pollution in the river.

MountainTrue’s Hartwell Carson, the French Broad Riverkeeper, has been monitoring the quality of the river’s water for nearly 20 years. He explains that levels of bacterial pollution did not suddenly spike triggering the impaired designation. Rather, levels of E. coli and fecal coliform pollution have stayed essentially consistent for several years.

The primary culprit causing bacterial pollution is rain run-off from livestock pasture lands. Failing septic and sewer systems are very much a secondary contributor. E coli and fecal coliform themselves are not particularly dangerous. But they are carriers of diseases that can infect swimmers and others who become submerged in and swallow river water.

During and immediately following deluges, pollution increases. As water levels drop, pollution abates. Excepting times when the river threatens to overflow its banks, the river is generally safe for canoeing or kayaking. If the river is muddy, Carson advises against swimming in the river. The USGS stream gauging station at Pearson’s Bridge in Asheville provides real-time water quality monitoring.

Managing rainstorm run-off is the key to sustaining water quality. Buncombe County set a goal of protecting at least 20 percent of the land in the county, focusing on preserving prime farmland and environmentally sensitive tracts. The initiative is partially funded by the county’s $30 million Open Space Bond approved by voters in 2022. Recent projects, 336 acres in the Eden Lake Preserve in the Swannanoa watershed and the 30-acre Parham-Fortner Farm on South Turkey Creek near Leicester, bring the county to within 1,049 acres of its goal. County Commissioner Terri Wells and her husband Glenn have placed their 100 acre family farm in Sandy Mush under conservation easement. They have installed fencing to exclude cattle from streams, planted native trees and riparian buffers to filter run-off, and taken steps protecting wetlands.

In a similar vein, Lisa Raleigh, executive director of RiverLink, reports that it is implementing an extensive suite of urban and rural programs to reduce stormwater runoff. Salient among them is the Central Asheville Watershed Restoration Plan overseen by Renee Fortner, RiverLink’s water resources manager. Fortner is working closely with Roy Harris and others to manage stormwater and establish walking paths and a memorial garden in the historically marginalized Southside community.

Terri Wells, Buncombe County Commissioner, and husband Glen, have placed their farm in Sandy Mush under conservation easement to ensure it will always be a farm (left). RiverLink and the historically marginalized Southside community are working together to control stormwater pollution into the French Broad (right).

An Economic Engine

About five years ago, more than a dozen nonprofit organizations, state agencies, and the City of Asheville banded together to form the French Broad River Partnership. Its mission is improving the health of the river to enhance its environmental and economic benefits. The partnership collaborates to ensure that the river and its tributaries continue to provide water for domestic and appropriate commercial use while supporting biodiversity, sustainable agriculture and forestry, and economic vitality.

In 2022 the partnership conducted a study that determined the French Broad adds about $3.8 billion annually to the economies of the towns and counties in the river’s watershed in North Carolina. Results were based on a survey of 453 individuals and 111 businesses. The survey was funded by the Community Foundation of Western North Carolina, Duke Energy, and the Ecology Wildlife Foundation Fund. The survey found that nearly 7 million visitors cite the river as influencing their decision to visit the region. Visitors generate about $3 billion in annual spending and support roughly 39,000 jobs.

Many feel the same way as Leah Wong Ashburn, President/CEO of Highland Brewing. “The river draws people,” she says. “It adds life and energy like no other feature of the area.” There’s no doubt about that. Just walk through Asheville’s River Arts District. Name the medium from basketry through glass, to painting, to sculpture and most disciplines in between. Among more than 200 studios in the River Arts District, an artist in your favored discipline is bound to be at work.

However, the River Arts District is undergoing a massive makeover. In the next three years or so, three large, multi-storied, mixed-use developments will construct approximately 750 apartments east of Riverside Drive along the river. Each of the complexes will set aside a number of affordable residences that meet the needs of modest income families. Each development will also include offices, stores, and studios for artists. In addition, two new hotels are planned.

When development is completed, the River Arts District will mirror similar successful evolutions of former industrial riverfronts in Greenville, SC, and San Antonio, TX. Each of these include river walks, but none so extensive as the Wilma Dykeman/French Broad River Greenway.

Completion of the final segment of the French Broad River Greenway along the west bank of the river creates a 3.1 mile loop uniting a suite of riverside parks: Carrier, Karen Cragnolin, Amboy Riverfront, and French Broad River. Across the river, the Wilma Dykeman Greenway adds another two miles of walking, jogging, biking trail through Jean Webb Park. In addition, a number of branch trails will connect downtown Asheville with its riverfront.

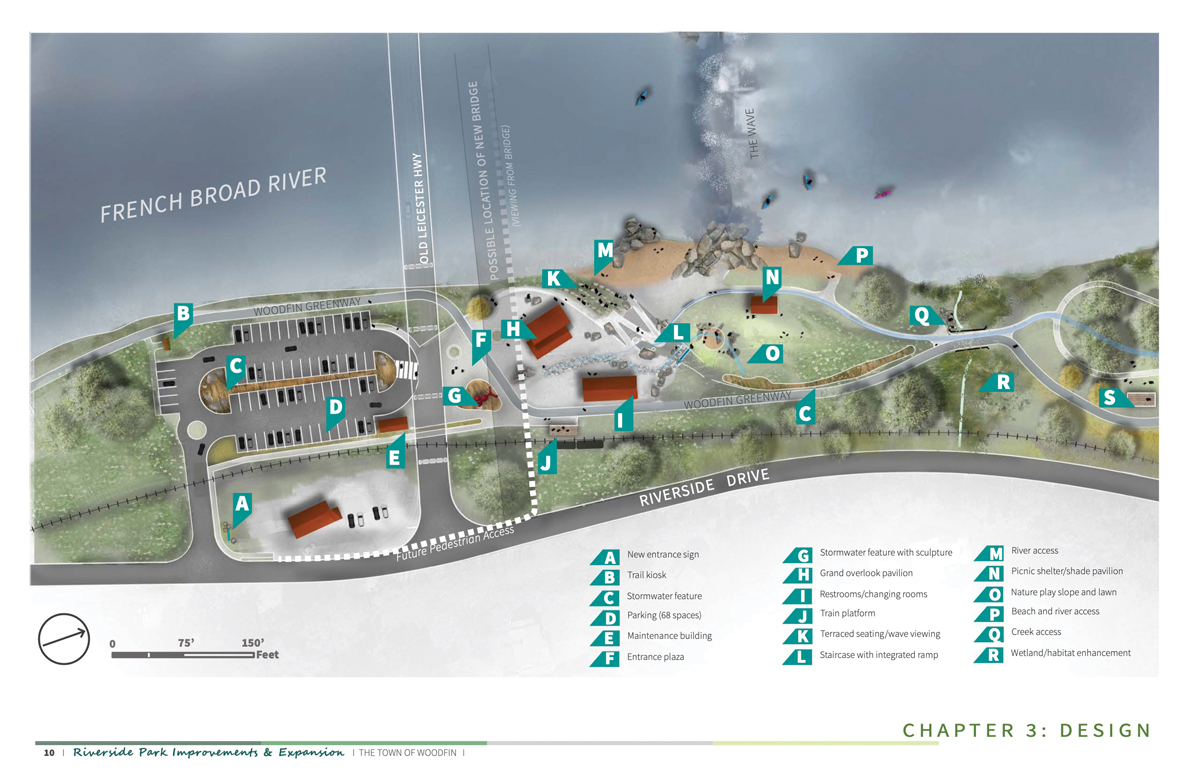

Featuring a permanent whitewater wave, expanded riverfront park facilities, and five miles of walking/biking trail up Beaver Dam Creek, project leader Marc Hunt envisions that the Woodfin Greenway and Blueway will add new riverside recreational opportunities as well as boosting the town’s economy.

Woodfin’s Whitewater Wave

Now under construction, Woodfin’s $34 million Greenway and Blueway have the potential to transform the riverfront of this small community in ways similar to, but much different from, the River Arts District’s impact on Asheville.

The core component of the Woodfin Greenway and Blueway is a perpetual five-foot-plus high wave crossing the river. When completed in the fall of 2024, the wave is anticipated to become a world-class destination for kayakers, paddleboarders, surfers, and canoeists. Marc Hunt, the visionary and community leader who helped initiate the project, believes it will add a completely new dimension to the river’s portfolio of recreational amenities.

No set of natural rapids along the river can host competitive whitewater events like the Woodfin Wave, Hunt believes. The project includes redesign of Woodfin’s Riverside Park to include a pavilion overlooking, an ADA compatible fishing pier, a children’s play slope, sanitary and picnic facilities, expanded parking, and easy access to the river.

Keyed into metamorphic geologic formations underlying the river, the Wave will be a submerged sloping wall made of rock and cement. Debris washed downstream will ride over the wall. The Wave will include a gentle side channel for boaters who want to avoid the feracity.

The channel will also add passage for migratory fish like species of suckers historically important to Cherokee and their ancestors. In addition, turbulence of the wave will oxygenate waters downstream, a benefit for the river’s aquatic life. The project also includes riparian buffers and stabilization of wetland habitats.

Along with the wave and refinements to Riverside and Silver-Line Parks, the Woodfin Greenway and Blueway includes five miles of 10-foot wide hiking/biking trail. The new route will run from Riverside Park down the French Broad to the mouth of Beaver Dam Creek then up the creek to within a third of a mile of Beaver Lake and its trail system in north Asheville.

Hunt believes that the trail will become a transportation corridor for residents who want to bike to work. “Popularity of e-bikes,” Hunt says, “will make this a viable alternative to commuting in cars.” In support of this idea, the US Department of transportation provided a $13 million grant for the project.

The Woodfin Greenway and Blueway is a joint project of the Town of Woodfin; Buncombe County and its Tourism Development Authority; North Carolina Departments of Transportation, Environmental Quality, and Natural Resources; and RiverLink. RiverLink is the non-profit partner in the development of the project providing assistance in project design and strategic fundraising.

Just upstream and across the river from Woodfin’s Greenway and Blueway is the Craggy Historic District. Added to Western North Carolina’s listings of National Historic Places last year, Craggy Historic District represents a classic railroad hamlet. The district surrounds four buildings and two other structures linked to the late 1890s and early 1900s when the Asheville and Craggy Mountain Railroad was laying track down the river. The A&CMRR built a depot near Craggy Milling Company’s grist mill close to Gorman’s Bridge on the road from Woodfin to Leicester.

Whether physically challenged or dare-devil whitewater paddleboarder, the suite of new amenities (right) at Woodfin’s Riverside Park will offer a few hours respite along the river for anyone looking to make a splash.

Downstream Dams

In North Carolina, three dams impede the flow of the French Broad and block seasonal migration of aquatic species. Craggy Dam is the uppermost, just downstream from Woodfin’s Greenway and Blueway. Craggy was the first. It was built in 1904 by W. T. Weaver Power Co. to turn generators, providing electricity for Asheville’s street cars. Next is Capitola, a remnant of the era of grain and textile mills at Marshall. And the third, Redmon, also built by Weaver, is two miles downstream from Marshall. All three are run-of-river dams meaning that flow of the river overtops the dam and that none provides flood control.

Jack Henderson, manager of MountainTrue’s French Broad Paddle Trail, is working with Madison County’s Department of Parks & Recreation and Equinox Environmental to improve river access, parking, and picnic areas at Redmon. Further downstream, NCDOT will be replacing the US 25/70 bridge over the French Broad. Construction is expected to begin in 2025. As construction proceeds, the Town of Hot Springs, NC’s Department of Wildlife Resources, and MountainTrue will be exploring new public access to open when the new bridge is complete in four years or so.

In 2022, American Rivers’ office in Asheville began considering requests from RiverLink, MountainTrue, and leadership of the Woodfin Greenway and Blueway project to remove Craggy Dam. The 120-year-old rock and concrete structure generates a small amount of electric power used by the adjacent Metropolitan Sewerage District’s wastewater treatment plant. As dams go, Craggy is relatively small, only 13 feet high. American Rivers is studying removal of the dam, and results are expected later this year.

To replace electricity for MSD’s plant lost by taking out the dam, additional solar panels could be added to those at Buncombe County’s old landfill nearby. Prior to removal, sediment collected upstream of the dam could be dredged and deposited in the old flume feeding generators. So doing, Hunt says, would provide the trailhead for a path along a restored section of the Buncombe Turnpike. Restoring the river’s natural flow would enhance habitat for mussels, which filter small particles of bacteria and algae from river water.

Craggy’s removal would open another 5 miles of free-flowing river. Removal would also allow development of a mile of hiking trail along historic Buncombe Turnpike, Western North Carolina’s first interstate highway. Along the turnpike completed in the late 1820s, drovers herded cattle, hogs, and even flocks of turkeys and ducks from farms in East Tennessee to markets in Greenville, SC. Drovers put up for the night at stockstands with inns, the ancestors of the region’s now-robust tourism industry.

A River for Connections

In wake of the pandemic, interest in river recreation and conservation has soared.

With funding from NC’s Trails Program, MountainTrue is upgrading river access and campsites along the 140-mile long French Broad Paddle Trail from Rosman to Newport, TN. The paddle trail starts downstream from Headwaters Outfitters where the forks of the French Broad come together. Jessica Whitmire, second-generation owner of this business started by her parents in 1992, says that the reach above Asheville is increasingly popular. She sees increased numbers of stand-up paddle-boarders as well as tubers on the upper river. Whitmire and her team also note, “more concerned users that want to help protect and clean the river.”

Nancy Diaz, MountainTrue’s southern regional director, echoes that observation. Climate change is her greatest concern. Storms of stronger intensity will increase run-off. Diaz oversees the two “Trash Trouts,” floating devices that collect debris in their open mouths, on streams in Hendersonville’s Oklawaha Greenway. Oklawaha means “slowly moving muddy waters” in the Cherokee language. How appropriate, that one of the streams along this greenway is Mud Creek. Diaz also works closely with organizers of community events like Hendo Earth Fest, the city’s celebration of Earth Day and the differences one person committed to conservation can make.

Not only can one person improve the health of the river, but the river can improve individuals’ social and emotional wellbeing. Leah Worley coordinates RiverLink’s new Out of School initiative. Every year, Out-of-School provides opportunities for 800 young people to pause from their cell phone-dominated world and visit the river, letting their minds flow with the water. Students in the program are encouraged to express their feelings through journaling; writing poetry or song; or sketching, painting, or sculpting. Out-of-School complements RiverLink’s RiverRats program that serves about 4,200 students annually with hands-on, river-based environmental education programs. Personally connecting with the river, Worley believes, can be very effective in mitigating stress of daily life, not just for kids but for all of us.