Appalachian National Scenic Trail

Appalachian National Scenic Trail

History

The Appalachian Trail (AT) is one more icon of North Carolina’s stature at the pinnacle of the National Park pyramid. When first proposed in 1921 by Benton MacKaye (Mc-KIE), the idea for a cross-Appalachian trail was labeled “an experiment in regional planning.” The AT would preserve the East’s wilderness while offering the laboring masses an uplifting escape from the manufacturing economy. It did both, but creating the AT was a huge task.

Within two years of MacKaye’s proposition, major trail organizations had endorsed the plan and built the first sections. In 1925 a Washington, DC, meeting created the Appalachian Trail Conference, which became the Appalachian Trail Conservancy in 2005. At the conference, MacKaye said, “the trailway should ‘open up’ a country as an escape from civilization . . . The path . . . should be as ‘pathless’ as possible.” The first version of the trail was built by 1937, surprising many New Englanders with how fast the Southern route became reality.

The original route ran from Cohutta Mountain in Georgia, across the Great Smokies, to Grandfather Mountain, through southwestern Virginia, Shenandoah National Park, and on to Mount Washington in New Hampshire. MacKaye called it the, “main line,” and suggested it link to, “branch lines,” meant to reach distant cities, funneling workers into a refreshing green corridor. Today, North Carolina’s Mountains-to-Sea Trail is surely the best example of what MacKaye meant.

The trail is ever-evolving. It was AT pioneer Myron Avery who said that it could never be said of the AT that, “It is finished—this is the end!” Thanks in part to the 1968 National Trails System Act, which designated the AT as the first “National Scenic Trail,” changes continue. More and more of the trail route has gone from private to public ownership. Every year, thousands of volunteers and dozens of clubs affiliated with Appalachian Trail Conservancy toil long hours in the task of maintaining their portions of the path and nearly 300 overnight shelters. That includes occasionally rerouting a path that’s always in flux.

A century after the trail was launched, the philosophical uplift that MacKaye hoped for has taken place. Our current outdoor lifestyle and environmental consciousness are traceable, in part, to the Appalachian Trail and the wildlands that enclose it. The path’s enduring grandeur inspires generation after generation. Perhaps more than any other recreational facility in the world, the Appalachian Trail symbolizes the power of nature to work wonders in the hearts and minds of those who simply take the time to wander in the woods.

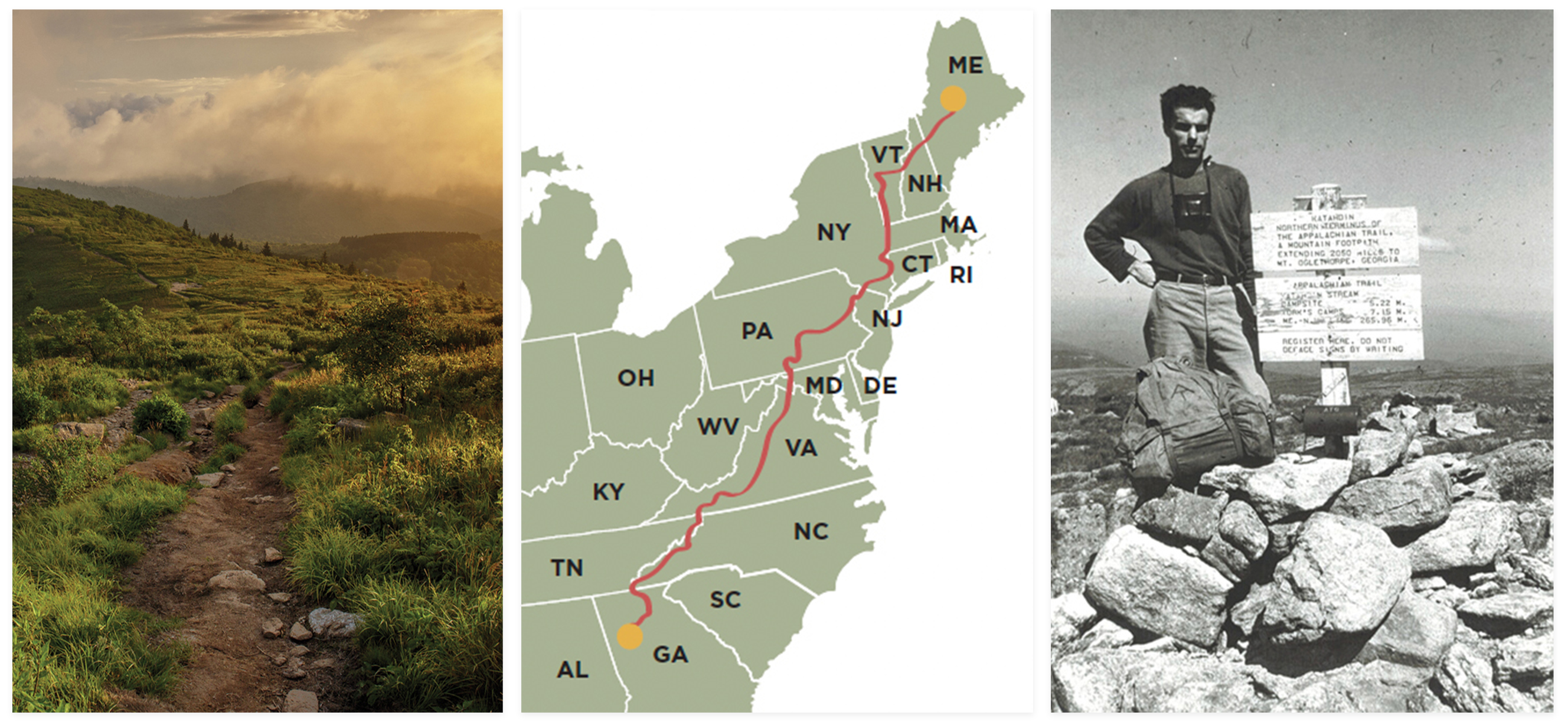

(Left to right) Along an open stretch of the North Carolina section of the AT, a bright sunset decorates the skyline; Earl Sheffer photographed here on Maine’s Mount Katahdin, is considered the first reported AT thru-hiker (1948).

Why Visit

It’s incredibly easy to say that you, “hiked the Appalachian Trail.” Almost-endless access points underline why, in North Carolina, wonderful day hikes may be a bigger part of the AT experience than the ideal of a 2,000 plus-mile, end-to-end hike. That arduous achievement eludes most who attempt it, but with annual installments, “section hikers” earn the honor more easily. Others just backpack single stretches. The trail has elevated some isolated mountain burgs into backcountry boomtowns. Celebrated as “trail towns” by the Appalachian Trail Conservancy, these are places to revel in the uniquely outdoorsy AT attitude.

Trail Magic at Trail Towns

- In North Carolina, Hot Springs (with its spas and TrailFest event on April 12-14, 2024), Franklin, and Fontana Dam all qualify.

- Nearby Damascus, VA, home to the Appalachian Trail Days Festival (May 17-19, 2024) is an easy spot to target from WNC.

- Western North Carolina earns accolades for distinctive locations like the Southern Appalachian “balds,” alpine-like grasslands on the Roan Highlands near Boone, and elsewhere.

- The lofty crest of the Great Smokies stands out too, as do the wilds of the Nantahala National Forest.

Learn more

The Appalachian Trail Conservancy aims to protect, manage, and advocate for the park. appalachiantrail.org