Conserving the Carolinas

Conserving the Carolinas: A combination of indigenous land management techniques and innovative approaches to restoration offers partial answers to the challenges of a changing climate in Western North Carolina forests

Big Yellow Mountain in Avery County is among dozens of grassy balds—treeless mountain tops—that adorn the high ridges of the Southern Appalachians.

At 5,400 feet, the meadow is home to rare species—such as the northern flying squirrel, spruce-fir moss spider, northern saw-whet owl and various songbirds. The larger and more connected their habitat, the more likely the animals are to roam freely and thrive. Yet, the grassy, high-altitude habitats are at risk of losing ground to invasive plants, trees, and shrubs.

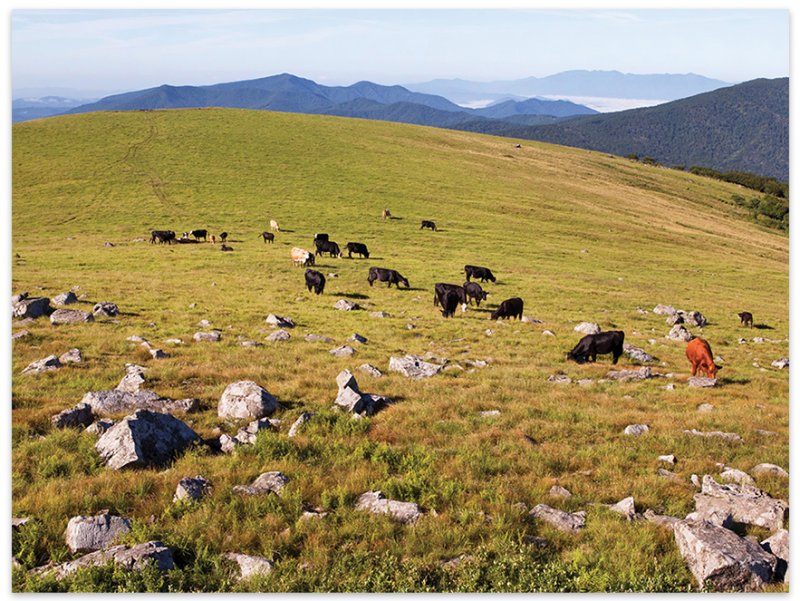

Through an arrangement with the landowner, a herd of cattle has been maintaining the grassy top. The presence of livestock on Big Yellow Mountain is the continuation of a decades-long family tradition of using it as a pasture. On one hand, the access to grassland supports the local economy, while at the same time preserving the bald’s open condition.

The arrangement, however, came perilously close to vanishing in the mid-1970s as the property was slated to be sold to a developer.

However, the deal fell through, and instead The Nature Conservancy, or TNC, purchased it in 1975. Currently, the grassy bald is managed jointly by the Southern Appalachian Highlands Conservancy and TNC as the Big Yellow Mountain Preserve and is still maintained by the cattle herd to prevent the incursion of trees and shrubs.

The mutually beneficial arrangement between private landowners and conservation organizations on Big Yellow Mountain is an illustration of a functional method to protect forests and habitats at a meaningful scale in order to conserve some of Appalachia’s most unique and threatened spaces that face an uncertain future as climate change barrels forward, altering how animals and humans use the landscape.

Big Yellow Mountain parallels other conservation efforts—one that extends across more than 1 million acres of national forest, and another focused on one valley in Buncombe County—each designed to prepare, protect and provide solutions for a forested landscape facing unprecedented environmental changes.

BIG YELLOW MOUNTAIN

Three decades ago, a student handed Peter Weigl, now a retired Wake Forest University biologist, a peculiar tooth he discovered in a wetland in Western North Carolina.

It was black and deeply carbonated, an inch long, and looked as if it had been buried for ages.

After some detective work, Weigl identified the specimen as a back tooth of a tapir—an herbivore that once roamed North America until its extinction more than 10,000 years ago. While the discovery wasn’t groundbreaking—other past megaherbivore remains have been unearthed in the region—the fossilized tooth helped unravel a fundamental mystery of the origin of some of the most precious places in the Southern mountains: high-elevation grassy balds.

The tooth was a clue to Weigl that a connection may exist between the extinct leviathans of another age and the balds. Other remains of giant herbivores in the Southern Appalachians, such as a site in Saltville, Va., are evidence that mammals with a tolerance for cold, big appetites and a broad range of mobility—such as mastodons, muskox, woolly mammoths, giant sloths, caribou and others—may have kept the forest from encroaching on high-elevation grassy tops as the climate warmed following the last ice age.

Although the giant grazing mammals were extinguished, possibly hunted to extinction by humans, their shoes were filled by other grazers such as elk and bison, which flourished until their own demise two or three centuries ago.

While the cattle on Big Yellow Mountain’s 500-acre grassy top keep this bald from being swallowed up by hawthorn trees, blackberry and invasive plants, they are also at the front line of protecting one of the Southern Appalachians’ most unique and endangered habitats from climate change.

The collaboration is an inventive method for the protection of vital ecosystems, viewsheds and green space that are part of a much larger conservation project. In all, beginning with the purchase of Big Yellow in 1975, more than 20,000 acres within the 65,000-acre Greater Roan Highlands landscape is public land and open to the public. The majority of the land within the landscape is conserved and managed by private landowners or conservation organizations.

While some may be surprised to see a herd of cattle in such a pristine place, the unique relationship between private landowners and conservation organizations is a central strategy in its conservation. Yet not only does it make economic sense to allow cattle to roam, but it may also have scientific rationale as an adaptation to climate change.

Then and now, the advance of forests and exotic plants threatens the grassy bald’s unique biodiversity. If balds close over, plant species that don’t tolerate closed forests die off. Rare animals that depend on the grassy tops would also vanish.

Weigl and Knowles, who first visited the Roan Highlands as an undergraduate on a field trip led by Weigl, conducted a global survey of grassland ecosystems and the potential role of past herbivores to support their hypothesis. They also plan to use historical photos to demonstrate the loss of high-elevation grasslands in the Roan.

“It’s just astonishing to me how much of the balds have closed in since the 1980s,” Knowles said.

“It’s incumbent on us to try to fix the damage or mitigate it the best we can. The current rate of warming is going to bring changes very quickly. These islands of habitat stand a good chance of being burned right off the top of the mountains.”

The pace of climate change and rapid loss of habitat also make it more difficult for species to adapt or move.

“Climate change and the loss of biodiversity go hand in hand,” he said.

While “rewilding” landscapes with grazing mammals such as elk is a long shot, Knowles is hopeful that humans with weed trimmers, and perhaps a herd of cattle, can accomplish what giant mammals did for eons.

SANDY MUSH

Grazing mammals have also been present in Sandy Mush, an agricultural community in rural western Buncombe County.

Much of the timberland on the steep slopes of the valley surrounding Sandy Mush was once pasture, but as the farming economy diminished over decades, lands once used to raise cattle, tobacco and other crops were abandoned. In its place, white pine, poplar and other pioneering tree species—along with nonnative plants—took advantage of the open conditions.

But over the last several decades, families in Sandy Mush and other rural portions of Western North Carolina have transitioned from farming as a primary occupation.

What’s more, the mountain slopes around Sandy Mush are dominated by rich cove forests: hardwood stands that are shady and lush and an ideal habitat for invasive plants. The forests were also utilized for grazing cattle, sheep, goats and hogs, which kept invasives at bay.

Without livestock roaming fields and forests munching multiflora rose and blackberry briars, invasive plants have blanked abandoned pastures and overrun timberland that are often at the edges of farms and communities.

EcoForesters, a nonprofit professional forest organization based in Asheville, launched the Sandy Mush Forest Restoration Coalition in 2019 to improve forest stewardship in a project area that encompasses a landscape of over 50,000 acres of farms and timberland in Sandy Mush, the majority of which is privately owned.

The project is in partnership with the Southern Appalachians Highlands Conservancy and the Forest Stewards Guild, a national nonprofit focused on forest conservation and management. Their hope is to build a network of community members and stakeholders focused on rehabilitating the forests of Sandy Mush.

“The future of the forests is not bright in Sandy Mush without some forest stewardship,” EcoForesters co-Director Andy Tait said.

“Considering the suite of environmental threats we all are currently facing, practicing good stewardship and forest management on private land is more critical than ever.”

Lang Hornthal, co-director of Ecoforesters, said the first steps have been to engage landowners in the community, build trust and share information about stewarding their forestland for the long term.

“If you really want to have a landscape impact, which we hope to do, you need to reach more people,” he said. “So, we saw an opportunity to connect with landowners in Sandy Mush that have a tradition of conservation and are facing challenging forestry issues.”

Yet, smart forestry practices that benefit individual landowners also deliver a meaningful public good by providing and maintaining ecological services, such as better water quality downstream, carbon sequestration, and charming scenery.

“If we can make our forest more resilient to climate change, the forest can better handle future droughts, floods and fires” that may accompany a changing climate, Tait said.

For instance, a healthy oak forest is better adapted to climate change than, say, yellow pine. Oaks are more drought tolerant and use water more efficiently.

“A diversity of species and the structure of different sizes and ages of trees, in general, is always better for forest health and resilience,” said Tait, adding that the greater diversity of habitat, the better adapted they’ll be to a warmer, wetter, drier, and generally more extreme and volatile climate.

For example, a hypothetical invasive pest attacking oak or poplar with the same violence of the chestnut blight around the turn of the 20th century would be devastating since oak and poplar make up a large percentage of the forest’s canopy throughout Western North Carolina.

The scope of the undertaking in Sandy Mush is unique, Hornthal said. To his knowledge, the scale of the project and its approach has not been attempted elsewhere.

The idea is that if a growing number of properties become more resilient to climate change over time, it solidifies an entire landscape.

While removing invasives and improving forest stands may provide a significant public benefit, such as more abundant game and preserving scenic beauty, finding the right economic incentives for cash-strapped landowners to manage invasives and engage in other forest restoration practices is a high hurdle.

“In the absence of climate change, we would still be trying to help landowners be good stewards of their property,” Hornthal said.

“So, put climate change on top of it, and any problem they had before is going to be exacerbated by droughts, floods, change in temperature, invasive plants, insects, whatever the next blight is.”

Among the project’s strategies is to encourage willing landowners to develop a forest stewardship plan and help them secure resources.

“This could be a pilot of how we can engage a rural community, understand their values and needs, and bring resources to them in order to solve some of their problems,” Hornthal said.

“One of the things we are mindful of is not telling people what they need to do with their forest and their land.”

“We realized, to be a true community project and to get genuine buy-in, we need to be transparent and invite them to tell us their needs and concerns and why Sandy Mush is important to them.”

FOREST PLAN AND TEK

While several generations have worked the land in Sandy Mush, the Cherokee and other Indigenous tribes have stewarded forest resources in the region for thousands of years.

Indigenous knowledge is a central feature of a revised forest resource management plan that will oversee more than 1 million acres of timber within Pisgah and Nantahala national forests. The plan is slated to be finalized this summer and will guide forest management strategies for the next two decades.

The planning process required the U.S. Forest Service to seek public input and support a focused effort on gathering what experts refer to as “traditional ecological knowledge,” or TEK, from people who have stewarded the land for several millennia.

The U.S. Department of Agriculture Forest Service Southern Research Station in Asheville is working with the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians to combine social, environmental and biological sciences to examine how their land and stewardship methods can help answer complex forest management questions to bring together Indigenous knowledge and scientific evidence to better inform conservation on a landscape level.

Currently, the Southern Research Station has a “memorandum of understanding” with the Eastern Band to explore areas of research of mutual interest around climate change and climate change adaptation.

The work includes studying culturally significant plant species whose populations may be vulnerable. For example, research by Michelle Baumflek, an ethnobiologist at the USDA includes comparing traditional harvest techniques for ramps with commercial methods to lend evidence to practices used for centuries by native gatherers.

“There are all of these amazing, beautiful, forested landscapes that people have been impacting for thousands of years without recognition,” Baumflek said, adding that culturally important plants may be on the “tribe’s radar in a way that they might not be for other resource agencies.”

That concern is not lost on Tommy Cabe, a forest resource specialist with the Eastern Band. He regards the tribe’s participation in the forest planning process as a way to communicate and explain their complex relationship with the environment of Western North Carolina. He has participated in the forest planning revision process as a participant of the Pisgah-Nantahala Forest Partnership.

And if any group of people in Western North Carolina can prevail, the Eastern Band has demonstrated its resilience after resisting violent removal by the U.S. government that nearly destroyed the Cherokee civilization in the Southern Appalachians.

“We may be tucked in this corner of Western North Carolina, but we are still here,” he said. “We’ve survived. There’s an opportunity for us to engage and to demonstrate our philosophy on landscape management.”

Cabe said the EBCI has recently approved the Cherokee Land Management Plan that oversees the stewardship of 56,892 acres within the Qualla Boundary, the official name for the Cherokee Indian Reservation in Western North Carolina. The majority of the land is in Jackson and Swain counties.

The plan, he said, prioritizes cultural values and traditions. He’s pleased to see that philosophy emphasized in the Pisgah-Nantahala forest plan and applied to land management practices throughout the region.

“We as native people did not neglect the land; we’ve worked in unison with the landscape,” Cabe said.

“We’re taught not to decimate the landscape. Otherwise, it will affect our bloodline for seven generations. That’s a long time, but that’s how we regard the land. That’s how we’ve always regarded it.” s s s

Because of its protected status, Big Yellow Mountain is not open to the public. Only guided walks are conducted. For more information, visit www.nature.org or email northcarolinachapter@tnc.org.