Clyde Smith - Trailblazer

Clyde Smith - Trailblazer: A mountain man who led the way to our outdoor life

The Southern Appalachians’ “age of exploration” was coming to an end by the twentieth century. A few hundred years of scientific sojourns by Andre Michaux, Asa Gray, and others were shifting toward recreational explorers.

Clyde F. Smith and his wife Hilda were among them. Smith was one of Eastern America’s quintessential mountain men, and his name crops up just below the radar of fame whenever the topic is trails.

The couple was rarely without a tool or two to widen the path as they spent their lives hiking the horizons of Western North Carolina and New England. Smith’s artful trail signs would point the way to adventure for countless hikers on Grandfather Mountain, Roan Mountain, and up and down the Appalachian Trail. The Smiths’ example helped set the scene for today’s outdoor lifestyle, and even our tradition of volunteer service to trails.

Inviting the Masses

Clyde Smith was one of many New Englanders drawn to Southern Appalachia. After the Civil War, the era’s horseback riding travel writers, or, more rightly, “travel riders,” explored the Southern mountains, filling postbellum magazine articles with romantic tales of isolated mountaineers.

Asa Gray called Roan Mountain, “the most beautiful mountain east of the Rockies,” and by his second visit in 1888, the mountain had a rustic summit lodge full of outdoor enthusiasts and amateur naturalists. More than a few were from New England, where the Appalachian Mountain Club was busy building trails and similar mountain huts in New Hampshire’s White Mountains.

The Carolina Mountain Club was founded in 1923 and hosted outings at landmarks far and wide. Famous club photographer George Masa attended one hike on Grandfather Mountain as it was being logged. A letter he wrote exclaimed that they, “skinned this old Grandfather!”

Great Smoky Mountains National Park was born in 1934, a decade after rustic LeConte Lodge got its start. Then came the Blue Ridge Parkway, which actually destroyed some early sections of the quickly-expanding Appalachian Trail. Today’s Southern Appalachian outdoor scene was on the horizon.

Snowbird Lifestyle

For a decade during the Great Depression, Smith (1906-1976), wife Hilda (1909-2009), and teenage son Clyde H. “Mickey” Smith (1931-2008) skirted past the Southern Appalachians pursuing an itinerant lifestyle between seasonal jobs in New Hampshire and Florida.

After their marriage in 1930, Smith and Hilda spent nine spring-to-fall seasons manning a fire tower atop New Hampshire’s 3,156-foot Mount Cardigan. The family lived in a mountaintop cabin, resupplying themselves on foot while Mickey hiked miles to school everyday. His dad's job included building and maintaining trails and shelters, and making routed trail signs.

Halfway through the fall school term, Mickey and his parents migrated to a new school in the heat of winter in south Florida. The couple worked in hotels and restaurants and called West Palm Beach and Miami home. For years they yo-yoed back and forth between subtropical tourism and fire-spotting from Cardigan, with Clyde plying an emerging freelance trade as a master maker of wooden signs for all kinds of businesses.

The couple’s 1930s diaries describe the seductive lifestyle enjoyed by some upscale Floridians today, going from peach clouds and a sultry winter climate in Miami to cool summers in the North Carolina mountains. The Smith’s cool summers were initially in New England, but they eventually found themselves in Western North Carolina.

Their Southern Appalachian saga started in 1933. Passing through Canton, they saw the smoking stacks of “the largest paper mill in US,” Hilda recorded. As they passed, wood from the slopes of Grandfather Mountain was being processed. The Smith’s drove their Mount Cardigan logo-emblazoned pickup truck, “over a red mud road out in no man’s land and almost got stuck,” she wrote. Actually, they did get stuck, spending their first winter in Western North Carolina in the early 1940s and would do so for decades. They settled in Spruce Pine, but their orbit included Blowing Rock, Boone, Asheville—and Grandfather Mountain.

Before the Swinging Bridge

Grandfather Mountain’s iconic Mile-High Swinging Bridge wouldn’t be built by future owner Hugh Morton for another decade, but there was already a tourist attraction called Observation Point. The road terminated far below today’s views on Linville Peak, at a rough-hewn parking deck built like the “board roads” recently used to strip the mountain of timber. Grandfather inspired Smith. Its thinned forests dramatically revealed the craggy, New England-like scale of peaks in the White Mountains where Smith had been born near Mount Washington in Gorham, New Hampshire.

Smith landed a dream job as a wintertime Blue Ridge Parkway ranger and became a leader in a Blowing Rock Boy Scout Troop where he and his 13 year old, later Eagle Scout, son Mickey would build a trail to the top of the High Country’s most dramatic summit. With Daniel Boone's footprints all over the area, and even the county seat named after him, Smith's path to Calloway Peak would be named after that old “scout” himself, Dan’l. His double-entendre title was the Daniel Boone Scout Trail.

Building the Trail

Smith targeted the logged and singed northeast flank of Grandfather for his trail. In 2012, the earliest map of the Boone Scout Trail was found, dating the opening of the trail to summer 1943. The builders included Smith’s son Mickey and a list of scouts including Frank J. Brown, who would become a physician (1932-2009). In the 1980s, Brown wrote, “Each weekday morning, Troop 21 “would load into Smith’s pickup” for a ride to the work site on US 221 (called the Yonahlossee Road when it was built from Blowing Rock to Linville in 1891). Smith’s son Mickey once told me that his father “made friends with an old lady who lived on the Yonahlossee Road—Miss Boyd—and got permission to start the trail on her property.” One of Smith’s routed signs marked the trailhead.

The troop “blazed a trail from Ms. Boyd’s store to a small grassy plateau ... Troop 21’s prime staging area in opening the trail to the top of Calloway Peak—and beyond.” That midpoint of the trail is still a state park campsite near a water source Smith named Bear Wallow Spring. Just below Calloway Peak, Smith and the Scouts constructed a unique lean-to trail shelter Smith named “Hi-Balsam.” A half-century later, Smith’s son wrote, “We built Hi-Balsam so the scouts would have a place to camp while working on the trails ... grand spot during thunderstorms and even some winter expeditions.”

Early summer residents heard about the Boone Trail. One of those families was the Chastains of nearby Blowing Rock. Reginald Bryan Chastain and Dixie Herlong Chastain (the first female graduate of the University of Miami Law School) bought sixteen acres in the mid-1940s and built a house south of Blowing Rock.

Their son and daughter, Richard and Dixie, encountered the Daniel Boone Scout Trail and, “we all wanted to go to the top,” Richard remembers. “Mom didn’t know what she was getting into.” The hikers encountered the distinctive markers Smith used—tin can lids painted white, with a red directional arrow styled like a Native American arrowhead, an oft-employed motif embracing the symbolism of Scouting.

After the Boone Trail, Smith and his troop kept going, opening what was likely the first formal recreational trail system on one of the South’s most spectacular mountains, a peak that for decades had attracted a who’s who of scientist explorers.

The South’s Most Scenic Hike

The mountain’s rugged summit ridge had defied easy access for millennia, but vague routes on Grandfather had been in use for years. Everyone from Michaux, to John Muir in the late 1800s, to author Margaret Morley in the early 1900s had struggled across the awesome summit spine of crags. Morley had hired some local guides to thin the vegetation as they took a hike she called “a knife-edge walk up in the sky.” By 1942, fire warden Joe Hartley wrote that he’d opened a post-logging “fire line over Grandfather Mountain” but when Smith and his Scouts found Hartley’s “pre-existing trail,” it wasn’t much.

Mickey Smith wrote that his father didn’t think “there was even a trail except for some game paths beyond the Attic Window.” It was exactly that remoteness that intrigued Smith and inspired the Daniel Boone Scout Trail, the Grandfather Trail, and other early paths on a mountain now known as one of the South’s adventure hiking destinations.

Thus, Smith gets the credit for formalizing the earliest basic paths we now associate with Grandfather, including, as Frank Brown wrote, “the Shanty Spring Trail from Calloway Peak down to Linville Gap (now NC 105 near Banner Elk) and the headwaters of the Watauga River” in 1944. Smith was also influential in naming the trails and landmarks, evidenced by his post-1943 map showing the trail later called Shanty Spring labeled as the Calloway Trail. That trail likely earned its name as the early-1900s connection to the old Calloway Hotel, starting point for many early adventurers. Versions of these routes likely came and went over decades, but Smith’s trails helped focus Grandfather Mountain’s modern identity, including providing Observation Point, and later the Swinging Bridge, with world-class trails that led the attraction into its current nature stewardship focus.

The Question of Ladders

Today, the Grandfather Trail’s scenic status is closely connected to its cliff-climbing ladders. Credit for that too likely lands on Clyde Smith.

Former Scout Frank Brown was certain that in 1943 the troop constructed “some 18 ladders over cliffs ... made of Balsam poles ... fastened with chains and/or steel cables to old Tweetsie Railroad spikes driven into rock crevices.” That seems to credit the Scouts with Grandfather’s ladders, but likely the earliest photo of a trail ladder on the mountain’s summit ridge was taken in 1913 by a party hiking just after Margaret Morley. Could that ladder have been her guides’ handiwork?

No one alive today can say, but Smith’s New England experience with trail ladders argues he would have built a ladder if one were needed—or the remains of one were found. Certainty eludes us, but most of the credit for installing Grandfather Mountain’s now classic, cliff-climbing ladders likely goes to Smith. By the time the 1940s ended, he’d connected Observation Point to the most remote summits and nearby valleys. But that was just the start. The North Carolina mountains would become Smith’s second, and final, home.

A Lifetime Outdoors

In May, 1952, Smith found his financial anchor—“full-time” summer sign work with New Hampshire state parks at The Flume where he retired in 1975. During High Country winters, freelance sign-making sustained him, including work for the Appalachian Mountain Club. Robert Proudman, the AMC’s onetime trail crew leader, recalls the thousands of “beautiful little basswood signs, white, with green lettering,” he’d make for AMC. “I always wondered how he did that distinctive, scalloped edge on his signs. When he showed me,” Smith’s finesse with a sharp little ax, “was amazing to behold,” marveled Proudman.

The Smiths were poor, but their lifestyle gave them countless days on the trail. They were among the first to cross country ski the Blue Ridge Parkway. Hilda learned to downhill at North Carolina ski resorts in the ‘60s, and Smith made the first version of the stylized skier sign still visible at Appalachian Ski Mountain in Blowing Rock.

He made huge signs too, for Appalachian State University, the US Forest Service, and Grandfather, where his signs became landmarks on the trails—and at Hugh Morton’s new Swinging Bridge attraction after 1952. In 1945, Morton told a board of directors meeting about the “close cooperation being carried on between Ranger Smith of the Blue Ridge Parkway and the Linville Company in the protection of Grandfather Mountain.” “Dad” as Hilda called Clyde, returned to hike on Grandfather’s trails for decades after the Scouts were grown and gone.

The Trail Beckons

Ultimately, America’s premier path inspired Smith and an endless assortment of his signs marked the trail from north to south. In 1966, Smith met Stan Murray, Chairman of the Appalachian Trail Conference (now Conservancy). The later founder of the Southern Appalachian Highlands Conservancy (SAHC) had suggested routing the AT over the Roan Highlands in 1952, now hailed as one of the most scenic sections of the entire AT. Smith himself designed and worked on sections of that trail.

For Murray, Smith’s offer to make signs for the Roan Highlands was “an ‘answer to a prayer.’” Smith’s elaborate AT signs, visible up and down the East Coast, included detailed, brightly painted, deeply-routed trail club logos for the Appalachian Mountain Club in New Hampshire, the Tennessee Eastman Hiking Club in Johnson City, and the Carolina Mountain Club in the Asheville area.

His signs capped Mount Katahdin, the AT’s northern terminus, for decades, and many are still displayed as art. Throughout lives of compulsive hiking, Clyde and Hilda Smith organized trail club “work trips” on the AT and Grandfather, where one newsletter noted Smith’s “diplomatic contacts” with Hugh Morton secured “toll free passage up the mountain.”

Clyde set a good example. Onetime Club chairman Powell Foster remembered Smith “leading trail, clearing with this ax in his ham-like hands ... then turning around to wait for the rest of us to catch up.”

Many recalled the famous time Clyde Smith took “a major fall from a ladder in the middle of a rocky cliff,” recounted Foster. “Scared us all to death. He just retrieved his basket-type backpack, took the climb again, with absolutely no comment.”

Smith personified the New England trail man, back when trails were steep and hiking wasn’t supposed to be easy. “Parts of his Falling Waters Trail in Franconia Notch are so steep, we used to call it the Falling Peoples Trail,” laughs Bob Proudman.

Besides being a skilled signmaker, Smith was a talented photographer whose finest images were color-tinted black and white photos. Imagine the Smiths' pride when son Mickey became an outdoor photographer for books and magazines like Backpacker.

Clyde Smith had Grandfather’s trails nicely marked, but, longtime gift shop manager Winston Church maintained, “he just kind’a slowed down and wasn’t able to keep up with it.”

Back then, Grandfather was a commercial attraction that did little to maintain the trails and nothing to promote them, so the AT got Smith’s later attention.

The Asheville-Citizen Times columnist John Parris was one of those who raved about Grandfather’s “Trail of Thirteen Ladders” in the late-1950s, but he marveled that Hugh Morton ignored the trails, “quite puzzling since ... the owner, never misses a beat on tom-toms, golden harp or delicate lyre to keep the name of his mountain before the public.” Parris realized “there’s a heap of folks, able and willing,” to hike “if they only knew….” Morton knew the Clyde Smith demographic wasn’t his customer. At least not then. It would be years before Morton realized that the backcountry could attract a “heap of folks.” Hiking baby boomers would arrive, but first, Clyde Smith’s trails on Grandfather were destined to decline and almost disappear.

Clyde Checks Out

By spring 1976, Smith was having health problems, Hilda recording, “Dad to Dr. Cort ... All good but heart beat.” On April 1st, 1976, Clyde, Hilda, and dentist friend Dr. Creston Barker were doing trail maintenance near Big Bald, south of Roan Mountain.

Hilda’s diary entry is like a silent scream from the page. “Dad died on the AT!” The Smiths’ daughter Nancy Smith Whiton, was told, “The dentist heard Dad stop chopping.” Barker found him “lying on the ground ... with no heartbeat.”

Whiton recalls, “for an instant,” Hilda hoped, “it was just a very bad April Fool’s joke.” Creston went for help. Before it came, snow was falling hard on Hilda and her dead husband. Smith had refused a pacemaker for an irregular heartbeat fearing “he would never be able to work in the woods again,” Nancy Smith concluded. “I'd say he died the way he wanted.”

It would take five years, but Tennessee Eastman Hiking Club chair Ray Hunt prevailed in having an AT shelter near Roan Mountain named after Smith. Stan Murray too was later honored with a namesake shelter on the highlands he helped save.

Hilda never saw her husband’s shelter. A few years after Clyde’s passing, she and son Mickey took a hike to the place Clyde died and installed a sign memorializing his years of volunteer trail work. She soon moved back to New Hampshire and died in 2009 after reaching the century mark, outliving her son who died in 2008.

The lifestyle of seasonal mountain work had been hard on Clyde and Hilda, but the diaries she left behind reflect no regrets. At the end of so many days in the woods, year after year, she penned, "a lovely day” in her diary. Clyde and Hilda’s lifestyle gave them a lifetime of "lovely days" to savor each other, the balds, and balsams of mountains like the Great Evergreen Grandfather.

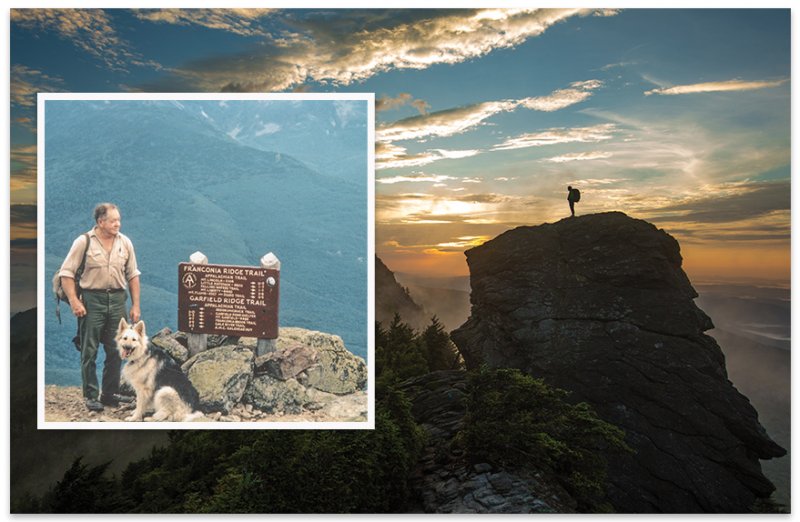

(Left) In 2021, CMC trail maintainer Randy Tarpley installed a modern memorial to Smith below the last fragment of Mickey and Hilda Smith’s 1977 marker. (Right) The father and son trail duo gaze over Maine on their last backpacking trip together.

A Journey with Clyde

Randy Johnson refelects on Smith's history and relationship with the mountains of WNC

INVENTING THE MODERN BACKCOUNTRY

Six months after Clyde Smith passed away in 1976, I was finishing trail management research for the Appalachian Mountain Club and US Forest Service near Gorham, New Hampshire, where Smith had just been buried. AMC trail crew chief Bob Proudman handed me a souvenir as I left—a small white trail sign with neat green lettering. “You’ve seen these and other Clyde Smith signs all over the Whites. It’s yours,” he said.

Hiking the next winter on Grandfather Mountain, a beautiful trail sign rotting on the snowy ground led me to the summit. A light bulb went off. Suddenly, signs on this mountain reminded me of Clyde Smith signs in New England. Could it be? Yes, I was still following Clyde Smith’s signs, and have ever since.

CLEARING THE TRAIL

On a later visit to Grandfather, a security guard turned me away from the trail. Smith’s trails were dangerous and disappearing. People were getting lost, one had died, and Grandfather owner Hugh Morton had closed the trails. I knew I’d try to reverse that decision. I visited Morton, and when he told me no one at Grandfather Mountain knew how to manage trails, I said, “hire me.” He did, and over years, Clyde Smith’s trails re-emerged, and the mountain achieved what wilderness management expert John Hendee called what “many have claimed could not be done”—create the country’s only self-sustaining program to manage private backcountry for public recreation.

Clyde Smith’s trails were reclaimed, his signs were restored, and the remains of his ancient ladders, still hanging from Tweetsie Railroad spikes, were rebuilt.

Grandfather’s waning trail reputation suddenly surged, adding outdoor adventure to attractions like animal habitats and a swinging bridge. Ultimately, the last stretch of the Blue Ridge Parkway opened in the late 1980s, bringing the Tanawha Trail, later part of the Mountains-to-Sea Trail, with it. New paths were opened as the backcountry program went on for decades until the mountain became a state park in 2009.

All that came back to me in 2021 as I pondered a big anniversary for a unique old trail shelter that Clyde Smith built on Grandfather Mountain. After years of searching, I finally surmounted a small cliff in 1980 and there sat a sagging lean-to structure, its roof pierced by an ice flattened grove of trees. The heart of the stalwart refuge still hid Smith’s sculpted sign, “Hi-Balsam.”

Volunteers and I rebuilt Hi-Balsam in 1981. Not long after, a letter arrived from Smith’s son Mickey, builder of the original. He'd hiked to the peak alone one day and was floored to find a reincarnated remnant of his youth. “I think my father’s spirit will continue through the rebuilding of Hi-Balsam,” he wrote. I imagined him reading the poster I installed in the shelter honoring his Dad In 2023, Smith’s old shelter will have been protecting pilgrims to Calloway Peak for 80 years.

I also couldn’t help smiling last summer when Carolina Mountain Club Appalachian Trail maintainer Randy Tarpley read my Grandfather Mountain book and approached me about an even older sign honoring Clyde Smith, that wife Hilda and son Mickey hung in 1977, not long after Clyde died on the AT. During Tarpley’s now 30 years maintaining the AT, he’d located the sign on a now-rerouted AT section, then couldn’t find it again. He’d recently rediscovered its decaying final remains and wondered if I knew what it said. He wanted to hang a replica.

I told him Mickey's sign read: “Clyde F. Smith carved and donated signs and devoted his time improving this trail. On April 1, 1976, gave his life that you might enjoy your hike.”

Working with CMC sign maker Tom Weaver, Tarpley’s interest inspired a new sign and in March 2021, he and friends installed the COVID-delayed monument on the old AT where Smith died chopping away a blowdown. A replica of the original may be in the works.

The sun eventually set on the accuracy of Smith’s old signs. Mileages changed and they were retired. But his work and his volunteer ethos still survives and illuminates the lives of the legions of us who live the outdoor life in Western North Carolina, and beyond.

Turns out I'd followed that Clyde Smith sign in the snow to a lifetime love of wild places and the trails that lead people to them. One day while reclaiming the mountain's trails, it was still laying there, so I packed it down to safety.

I won’t say where, but a few of Smith's masterful signs still hide on my favorite mountain.