Yeah, Baby

Yeah, Baby: Asheville’s Gerber factory was an economic and community cornerstone that fed millions of little ones

Memories form as early as toddlerhood—and for generations of Western North Carolinians, those memories began with the aroma of Henderson county apples and other fruity delights that eddied along harvest season’s cool mountain breezes. Nearby, such mouth-watering fragrances were the smell of money.

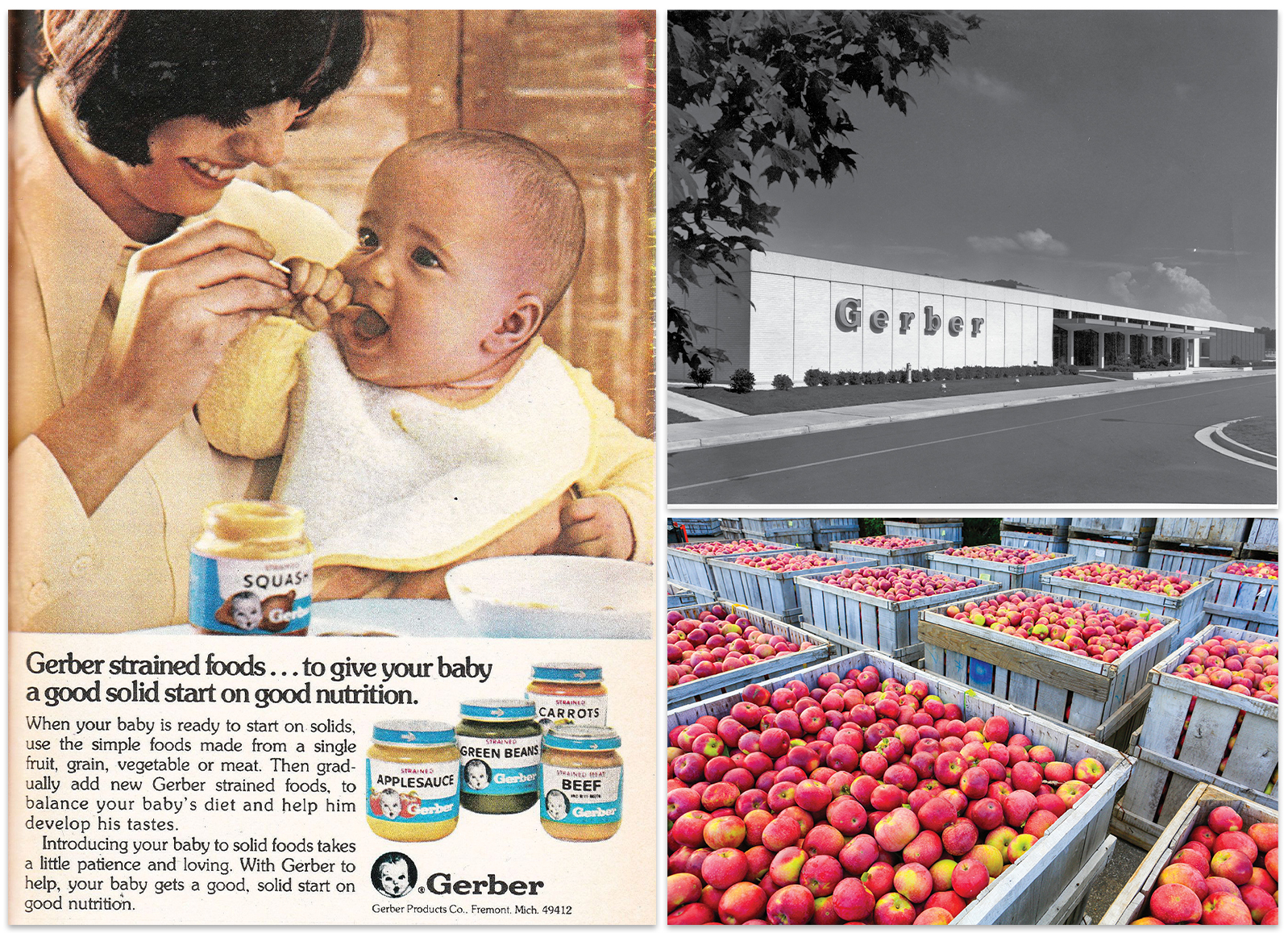

In the late 1950s, the Gerber baby foods company established its third production plant in the United States, in Asheville. By then, the iconic image of a doe-eyed infant affixed to little glass jars—along with the emulsified fruits and veggies within—had made Gerber a ubiquitous national brand. And in this corner of Western North Carolina, feeding little babies became big business for the company’s employees and local farmers alike.

Babies are our business

The Gerber corporation was born in 1927 in Fremont, Michigan, where parents Dorothy and Daniel Gerber started straining fruits and vegetables on recommendation of their infant’s pediatrician. The couple owned a canning business and decided to make junior’s vittles right in the shop, striking gold along the way. Within a year, their canned baby foods were lining grocers’ shelves across the nation.

The company has lived up to one of its slogans: “Babies are our business … our only business.” Today, Gerber is owned by Nestlé and makes an estimated 200 baby products—everything from food to clothing to medicine—for consumers in 80 countries. Since 2018, it has sold more than $1.26 billion dollars of products worldwide.

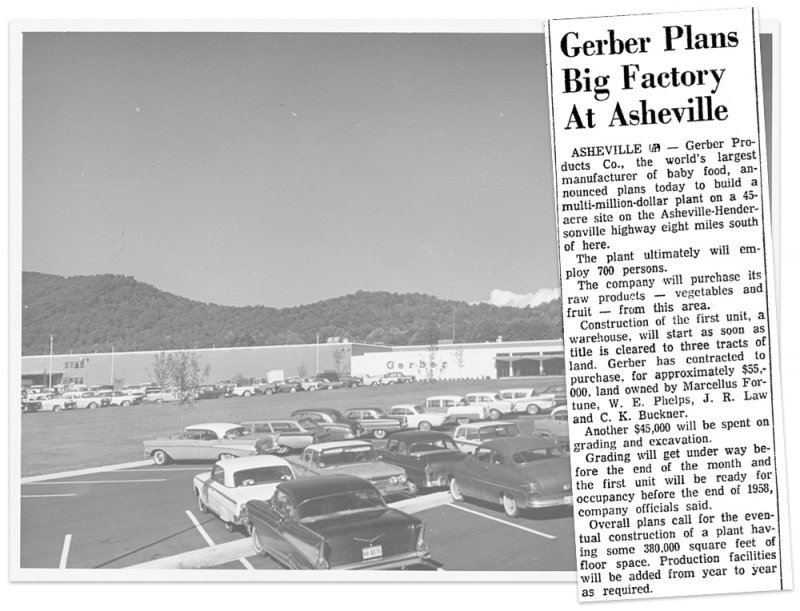

Flashback to 1958, when the company announced it would establish a regional factory in south Asheville, just off Hendersonville Road, and construction rapidly began at the 45-acre plant site. “Its payrolls will be added to the economic life-stream of the mountain area,” the Asheville Citizen noted in a welcoming editorial. “Its purchases of fruits and vegetables will add substantially to the cash incomes of growers.” The factory, the newspaper anticipated, would provide “the kind of industry this state needs in order to tie together agricultural and industrial production.”

On November 16, 1959, the plant began production in full swing with its several hundred new employees (700 were employed at its peak). Over the following decades, it would steadily expand its operations, eventually filling as many as 2.1 million jars a day.

Soon, local farmers were receiving upwards of a million dollars a year from the company for produce they’d sent from farm to high chair. One of them was Larry Halford of Enka, who spent his summers in the early 1960s as a teenager harvesting carrots and squash for the factory. “It was the best quality, and people knew it,” he says of Gerber’s products. “No one trusted any other company but Gerber.”

Community company

Gerber’s role in the area took multiple forms besides providing jobs and making baby food. The company conducted blood drives and other community events, and its employees and their children were eligible to receive college scholarships from Gerber. At the same time, local families donated recyclable glass to the Ball Corporation, which was next door to the baby food plant and had a long-lasting symbiotic relationship with Gerber, providing its jars. And some invested in Gerber Life Insurance after the company established that wing in 1967.

The company expanded the local agricultural economy in numerous ways, sharing its specialists to help farmers produce better apples, beets, blueberries, carrots, green beans, peaches, pears, and sweet potatoes. What’s more, it supported young growers in local chapters of Future Farmers of America and 4-H.

Some found inspiration within the factory to pursue their own culinary passions. For example, Hunter Lewis, the current editor-in-chief of Food & Wine magazine, spent childhood days golf carting around the plant site, which was long managed by his grandfather. “It was a pretty cool thing as a kid to be in the baby foods plant,” Lewis recalled in a 2016 interview with Asheville radio station WCQS. His favorite part? The applesauce-making room.

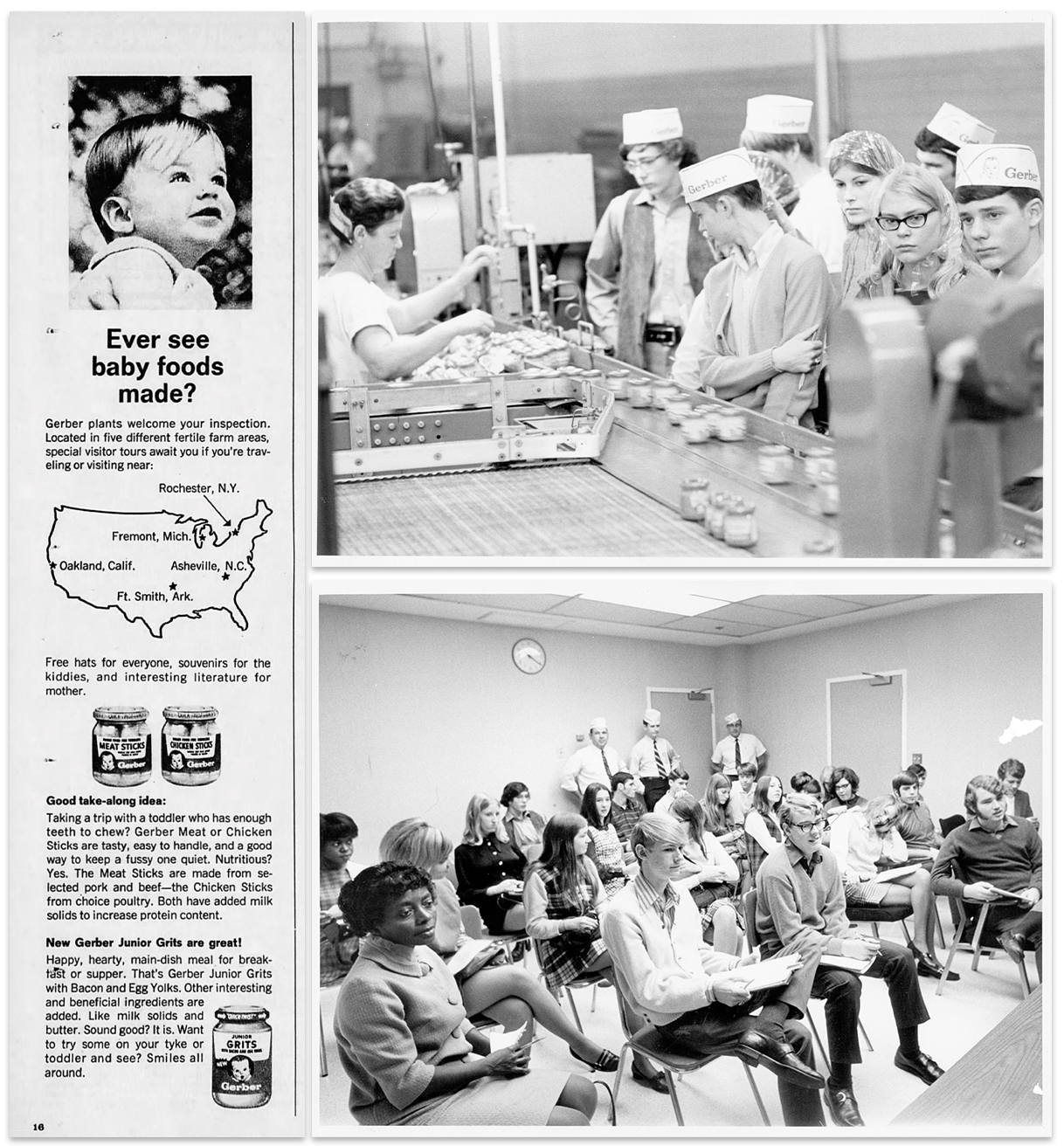

Educators appreciated the Asheville Gerber plant as a unique field trip experience for students, who got to witness the factory’s operations firsthand. Like Lewis, many specifically enjoyed the applesauce room. “I always remember about this time of the year they would can applesauce. The smell was amazing!” Asheville resident Paula Crowder recalled in a local history forum on Facebook. Others remember the necessity of wearing hair nets and the gripes of some students who loathed them—but at the end of the day, each received a commemorative spoon to take home, which is now a soul-stirring relic of the past.

“I always remember this time of year they would can applesauce. The smell was amazing!” —Asheville resident Paula Crowder

Bye-bye, baby

A warm sense of nostalgia shapes the memories of former Gerber employee Clyde Davis. He started working at the Asheville plant as a young man in 1963 and remained for 13 years. “Everyone was like family there,” he says. “They were the finest people I’ve ever had the pleasure to work with. It was just a real good place to work back then because everyone got along well.”

However, it was an unfortunate day in 1997 when employees and farmers learned that the factory would close its doors in less than a year. Some 460 people lost their jobs. A number of factors led to the closing, among them the dwindling rate of births in the United States.

“People were tore up,” Davis remembers. “No one saw it comin’, and it was heartbreaking because we lost what held generations of family and friends together for many wonderful years.”

Today, former employees keep the plant’s memory alive through tales of remembrance. A stroll through what is now the Gerber Village shopping center, a mixed-use development that was purchased in 2003, reveals some lingering hallmarks of an illustrious industry—one that continues to feed millions of babies around the globe today.