Senator Sam’s Secret Wars

Senator Sam’s Secret Wars: Burke County native Sam Ervin Jr. stuck to the Constitution through clashes with McCarthy, the Army, CIA, and Nixon

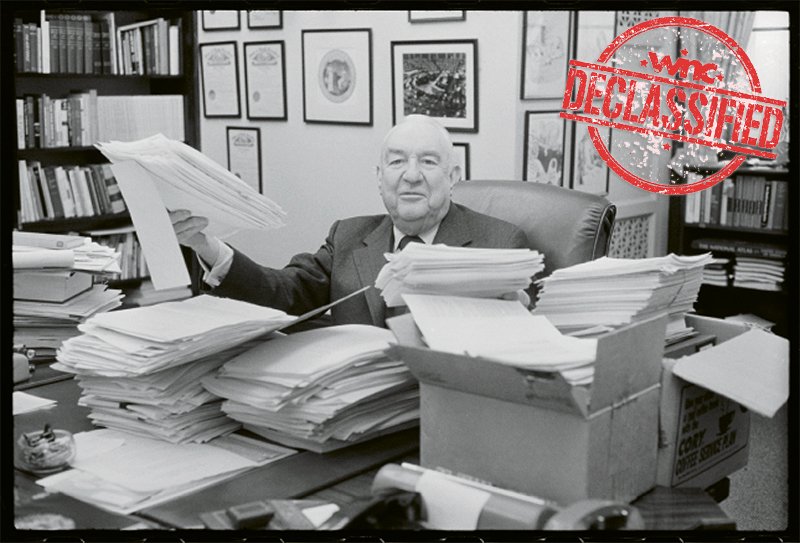

Ervin helmed Senate investigations that freed up thousands of pages of declassified material on everything from Army spying to Watergate.

A president hounded by accusations of secret payoffs, campaign finance violations, and election conspiracies, with a shady cast of characters and a special prosecutor in the mix—sound familiar? It certainly would have to the late Sam Ervin, the US senator whose investigation of the Watergate affair and related abuses led to President Richard Nixon’s political demise.

Always content to fashion himself as an “old country lawyer,” Ervin was in fact a razor-sharp constitutional authority and investigator. And, as both the public record and declassified papers show, he was willing to wade into some of the country’s most vexing questions of law and order, even when it placed him head-to-head against intelligence agencies and the White House. Along the way, he never lost his drawl, small-town charm, vast literary knowledge, and wit—all of which he employed to topple a president.

A Segregationist Anti-McCarthyite

Born in Morganton in 1896, Samuel James Ervin Jr. lived for almost a century and played a key role in many of the twentieth century’s major political epochs. He fought with distinction in World War I before blazing through Harvard Law School, then served as a state representative and state supreme court justice before being appointed and elected to a US Senate seat, which he held from 1954 to 1974.

From his first weeks in Washington, Ervin drew national attention. On the one hand, he was one of the South’s most eloquent opponents of desegregation, devoting his rhetorical talents to opposing civil rights for black Americans. It would prove to be the lowest point of his otherwise lofty career.

“There is some irony in the fact that Ervin … became one of [the Senate’s] most distinguished advocates to the constitutional right to privacy,” Appalachian State University assistant history professor Karl E. Campbell wrote in Senator Sam Ervin, Last of the Founding Fathers (University of North Carolina Press, 2007). As Campbell noted, Ervin attributed part of his disdain for government intrusions on personal life to his father’s angst with overstepping moonshine revenuers in Western North Carolina.

On the other hand, Ervin immediately smelled a rat in fellow senator Joseph McCarthy, the red-baiting charlatan who made bogus claims of communist infiltration of federal agencies, citing nonexistent secret information and destroying innocent public servants’ careers along the way.

At a key point in the 1954 deliberations about McCarthy, Ervin—fresh into his first year in office—unleashed a speech on the Senate floor that already contained what would become his trademark mix of folksy wisdom, Bible quotes, passages from other literature, and devout constitutionalism, while cutting to the crux of the matter. “Does the Senate of the United States have enough manhood to stand up to Senator McCarthy?” he asked near the end. “The honor of the Senate is in our keeping. I pray that senators will not soil it by permitting Senator McCarthy to go unwhipped by senatorial justice.”

Taking Back Liberties

McCarthy was promptly pushed out of office, but the powers of the government to impinge on individual liberties remained a preoccupation of Ervin’s throughout his time in office. In 1966, he was appointed chair of a Senate subcommittee on constitutional rights, a position that would shape his fate, spark his most notable work, and change the laws regarding Americans’ rights to privacy and freedom from government meddling.

In the late 1960s, Ervin led hearings on how federal employees were vetted and hired. At the CIA and other intelligence agencies, he found, inquiries into a person’s background and current life were virtually unfettered, probing the most secret of personal matters. The unspoken elephant in the room was the CIA’s desire to screen out homosexuals from its ranks, lest they be blackmailed by foreign intelligence services.

Numerous declassified documents show the agency’s concerted effort to exempt the CIA from Ervin’s law via backroom consultations with members of Congress who didn’t share Ervin’s values. “Apparently, what they want is to stand above the law,” he said of the CIA’s opposition to his proposed privacy-protection legislation.

The CIA ultimately won most of that battle but earned the persnickety senator’s lifelong opposition to its expanding powers. As the debate boiled in March of 1969, Ervin penned a blunt letter to CIA Director Richard Helms. “I believe that the CIA now enjoys as totalitarian powers as can be tolerated in a free society,” Ervin wrote, citing “basic rights belonging to every American.”

Ervin locked horns and faced similar resistance with the military. In 1970, a former Army intelligence analyst, Christopher Pyle, walked into Ervin’s office with a startling revelation: Military agencies were making a regular practice of infiltrating and surveilling US activist groups against the war in Vietnam, along with other protestors, while cataloguing all they learned in secret computers—a system taking on the aura of a police state.

Ervin responded by hiring Pyle as a consultant and launching investigative hearings. The Army’s surveillance was “a violation of the First Amendment rights of our entire nation,” he told the Senate. His hearings did much to expose the domestic spy network, but the Army orchestrated an elaborate cover-up. And as Ervin’s inquiry faded from the headlines, it was overshadowed, most of all, by a looming conflagration with the secrecy-obsessed Nixon administration.

The Watergate Showdown

In July 1972, five men were caught snooping around the Democratic National Committee offices at the Watergate hotel and business center in Washington, DC. Less than a year later, Ervin was placed in charge of the Senate’s Watergate committee, which probed the incident so thoroughly that it would prove Watergate to be just the tip of the iceberg of Nixon and his aides’ high crimes.

From the declassified documents and Nixon’s own secret White House audiotapes, it’s clear that the president and his inner circle knew they were in for trouble. “This old fart is trying to screw us,” Nixon said in one Oval Office meeting. Ervin, he said in another, was an “old incredible bastard” who was playing a “pissy-ass game.”

Still, Nixon proposed that his staff forge an accommodation with Ervin, insisting, for example, that the Senate committee would not have access to key presidential records about Watergate and related matters. Ervin nonetheless pressed forward to find a full account of what had taken place.

Realizing that, Nixon and his inner circle resorted to slamming Ervin in their private, increasingly consuming conversations about Watergate damage control. Press Secretary Ron Ziegler assured Nixon that “Sam Ervin is just a pompous fat ass.” “A real jackass,” Chief of Staff H.R. Haldeman chimed in at one point. “Get me some dirt on Ervin,” presidential counsel John Erlichman pleaded, to no avail.

In the summer of 1973, Ervin’s committee exposed the existence of Nixon’s secret White House taping system, the transcripts of which would lead to the president’s resignation. Ervin noted that the administration had done far more than Watergate: It had also subverted justice through covert political operations of the sort that a democracy ignores at its peril.

“Today, President Trump and his administration are accused of actions even more dangerous than Nixon’s imperial presidency,” says ASU’s Campbell. “Sam Ervin would be furious and remind us that each generation of Americans has a responsibility to fight for our constitutional freedoms.”