Into the Woods

Into the Woods: Through thick and thin, the Biltmore Forest School planted the seeds of modern forestry

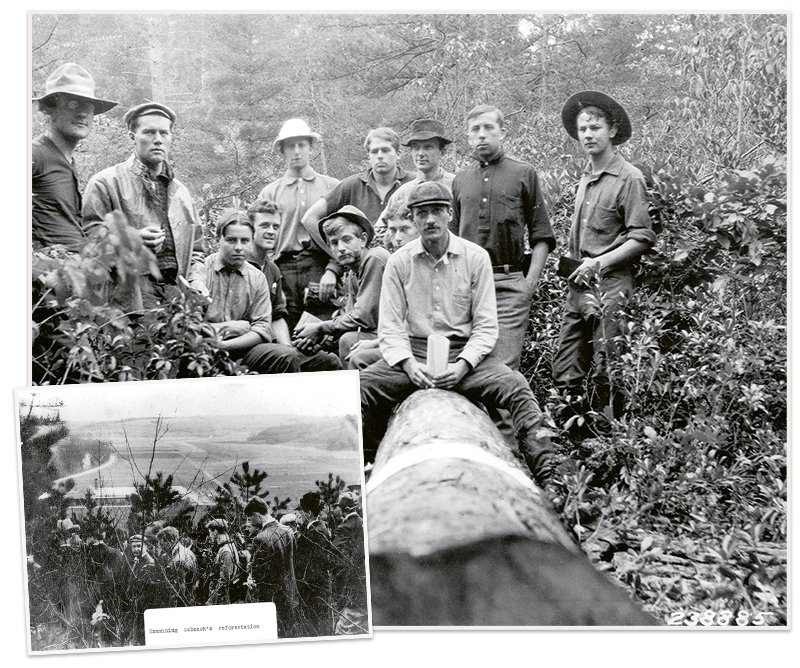

While the Biltmore Forest School offered no shortage of academic coursework, it equally emphasized training in the field. Here, the school’s class of 1905 pauses from work in the Pink Beds section of what was then Pisgah Forest in Transylvania County. (Inset) At a three-day festival of learning in late 1908, the school hosted scores of prominent specialists and officials to showcase Carl Schenck’s advances in forestry. Photographs courtesy of Forest History Society, Durham, NC

Pisgah National Forest’s present footprint—more than half a million acres—gives only a partial impression of its origins. When the federal government created it in 1916, Pisgah encompassed about 90,000 acres, much of which was bought on the cheap from Edith Vanderbilt, who was cutting costs after the untimely demise of her husband, Biltmore Estate progenitor George Vanderbilt. Yet it was already on its way to becoming part of something magnificent, a national resource that would stand the test of time.

Even as the Vanderbilts faded into the Gilded Age’s twilight, they left a legacy that impacts significant swaths of Western North Carolina, and indeed forests throughout the country, to this day. And while Biltmore’s foundational relationship with American forestry has become the stuff of sizable legend, it’s actually the story of a small school that was as full of ups and downs as Mount Pisgah itself.

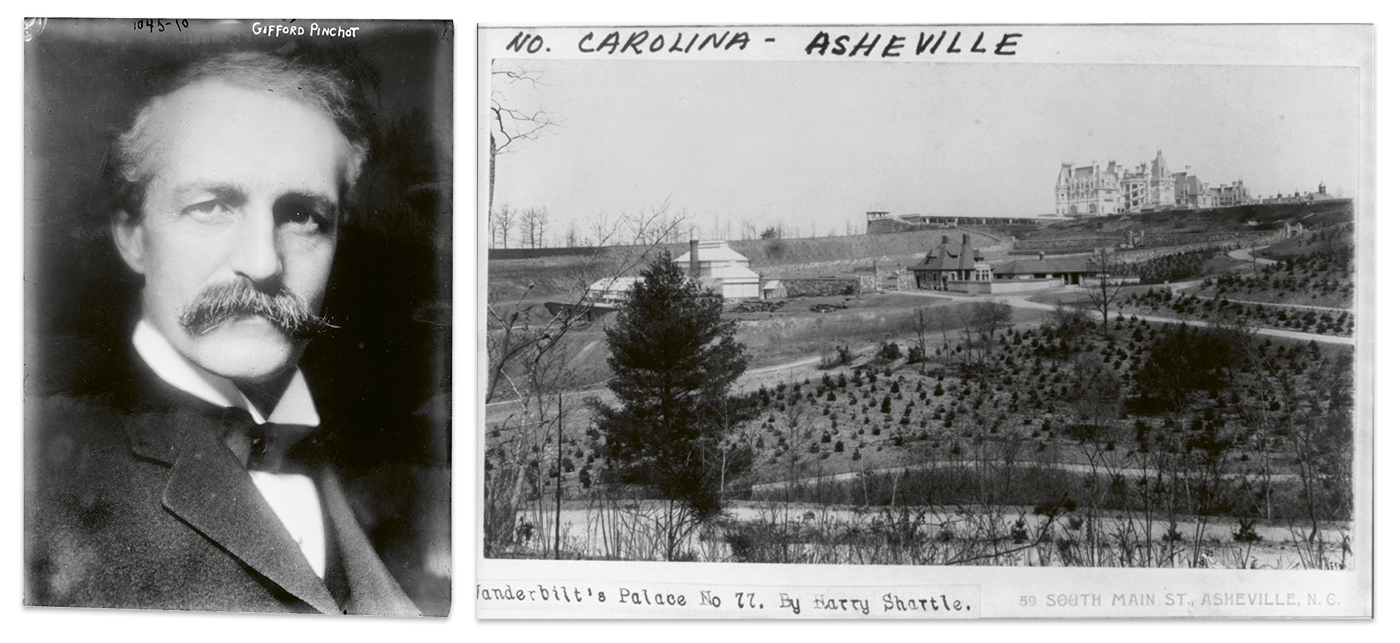

Biltmore’s first forester, Gifford Pinchot (left), faced the challenge of artfully propagating trees on an estate (right) that was largely barren. Photographs courtesy of Library of Congress

Breaking New Ground

The vision that determined the fate of millions of trees was in some respects the product of just a few figures, some exceedingly wealthy, some far less so but outstanding in their field. Vanderbilt sought to create an estate that would rival the finest in Europe, with no expense or expert spared. He hired the father of American landscape architecture, Frederick Law Olmsted, to lay out the grounds, and with Olmsted’s help, Vanderbilt recruited two of the leading lights in what was then the new science of forestry.

First came Gifford Pinchot, who was born in Connecticut but trained at a top forestry school in France. At Biltmore, he found an estate that looked very different than it does today, with scraggly vegetation and barren slopes marking much of the land, a situation he painstakingly tackled with a new forest plan for the property.

Pinchot left Biltmore in 1895 and would go on to become the first director of the United States Forest Service. Meanwhile, Vanderbilt continued to expand his local land holdings, buying up vast swaths around Mount Pisgah as he gazed at the mountain from his palatial home. To manage his enormous stock of woodland, Vanderbilt hired Carl Schenck, one of Germany’s leading foresters.

Schenck expanded the forestry efforts at Biltmore and its environs, launching massive surveys of the woods spread around Vanderbilt’s then more than 100,000 acres. Schenck set about finding new uses for the forests, running the spectrum from strategic conservation to (potentially) profitable logging. It was a massive endeavor, and the devoted European was clearly going to need some help from curious and hardworking Americans.

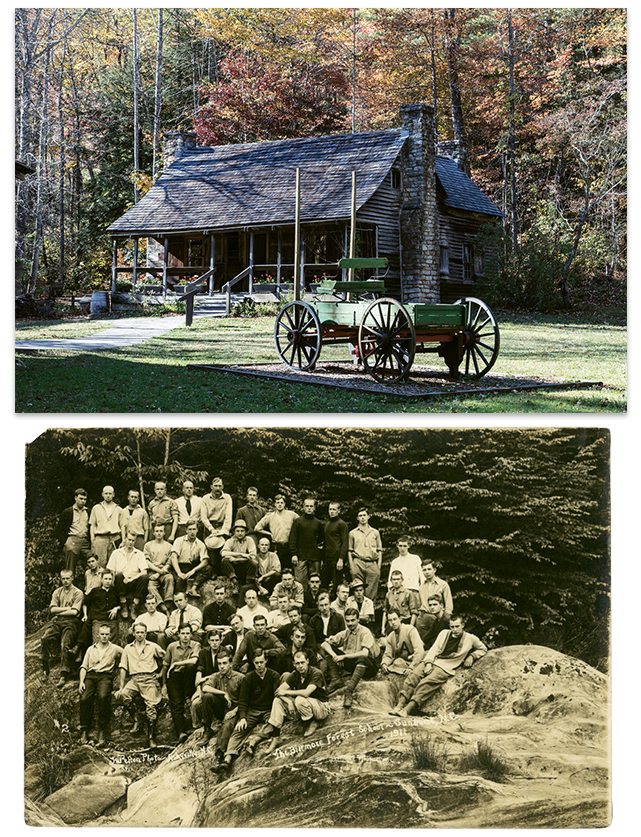

Headmaster Carl Schenck (top left), ever the disciplined German, built a hardy rapport with his mostly American students. At rustic buildings like a student quarters dubbed “Hell Hole” (bottom left), he encouraged blowing off steam with nighttime drinking and singing sessions. Photographs (Schenck, students working, students relaxing) courtesy of UNCA Ramsey Library Special Collections; (cabin) courtesy of Library of Congress

Growth Spurt

As Schenck expanded Vanderbilt’s woodland endeavors, an increasing number of young men applied from around the country to assist him. In 1898, he capitalized on the outpouring of interest by founding the Biltmore Forest School, the first of its kind in the country (although prominent American universities, notably Yale and Cornell, would promptly start their own).

The students at Biltmore usually trained for a year or so, spending roughly half their time in classrooms and half in the field. “My boys worked continuously in the woods,” Schenck boasted, “while those at other schools saw wood only on their desks.”

The instruction was rigorous, but also somewhat improvisational: there were virtually no textbooks, so Schenck scripted his own lessons. Reading them today, it’s remarkable how much ground was covered in the coursework, from plant biology to propagation, from road-building to lumber-harvesting and processing. Schenck also stressed the business end of forestry: he was working for a private owner, after all, and part of his charge was to make Vanderbilt’s forests lucrative, which proved a daunting task. “That forestry is best which pays best” was one of Schenck’s mantras, but ultimately Vanderbilt wouldn’t see a profit from logging on his lands.

On the one hand, life at the school could be a spartan affair, especially during the summer sessions at the Pink Beds in Transylvania County, where the students lodged in cabins they named Hell Hole, Little Hell Hole, The Palace, Little Bohemia, and Rest for the Weary. Days were spent studying in an equally rustic schoolhouse and working tirelessly on mapping, improving, and harvesting from Vanderbilt’s forests.

Some of the students’ weariness was assuaged with riotous nights of poker and drunken singing sessions dubbed “sängerfests” in a nod to Schenck’s German background. Inman Eldredge, a student who attended in 1906, fondly recalled: “[Schenck] taught us the value of relaxation in good company, when with song and stein the whole school and faculty would make merry and stretch lusty harmony and a keg of beer well into a starry Saturday night. Such carryings-on made for an esprit de corps and a strong bond of brotherhood.”

Through all the toil and merriment, the Biltmore Forest School made local forests something of a national workshop, with students and professors from other schools, industry leaders, and government officials gravitating there to see Schenck and his pupils at work. Their efforts culminated in 1908, when they hosted a Forest Festival marking the school’s 10th anniversary. Drawing about 100 visitors from around the nation for a three-day celebration and intensive learning experience, the festival heralded a new “epic in American forestry,” The American Lumberman declared.

Classes at the Pink Beds were held in this building, where students would sometimes gather to traverse Pisgah Forest on horseback. Photograph courtesy of Forest History Society, Durham, NC

An Evergreen Dream

Suddenly, however, 1909 brought reversals of fortune. To begin with, Vanderbilt found himself financially overextended, and began a push to sell portions of Pisgah Forest, Schenck’s budding masterwork. The two men squabbled over resources and plans for the future, and their relationship quickly ruptured, with Schenck ultimately suing Vanderbilt for back pay.

Loosed from both Biltmore and the Pink Beds, the Biltmore Forest School relocated to Sunburst, a logging village in Haywood County owned by the Champion Paper Company. From that base, the students increasingly went on the road, surveying forests throughout the United States and in Europe.

The school’s reputation remained sound, but its coffers were increasingly bare, and a growing number of competing forestry programs at major universities was sapping its student body. In 1913, having failed to find funding to continue operations, Schenck closed the nation’s first professional forestry school.

After his split with Vanderbilt, Schenck moved the school to Sunburst in Haywood County (bottom). Above, the Cradle of Forestry, the National Historic Site that continues to carry on the school’s educational mission today Photographs (Cradle of Forestry) courtesy of Library of Congress; (students) courtesy of Forest History Society, Durham, NC

“Retrospectively, let me assert that the Biltmore Forest School died at the right time,” Schenck wrote after returning to Germany. “It died when it had reached the apex of its career. Be it man or tree or institution, it is better to die too early than too late.”

Though it was open a mere 15 years, the school’s influence is hard to overstate. Of the 360 men who attended, about half went into forestry professionally, with many achieving prominent positions in the field. They became key players in the US Forest Service, state forestry agencies, leading academic programs, and major lumber companies. And like Schenck, some of them had a truly international impact, nurturing forests in countries around the world.

More than a century later, Biltmore Forest School lives on in spirit at the 6,500-acre Cradle of Forestry, a National Historic Site near the Pink Beds that was established by Congress in 1964. Several of the old school buildings have been authentically restored, and new generations of foresters along with students of all ages still flock to the place to learn Schenck’s lessons. Though he passed away in 1954, two years after his final visit to Pisgah National Forest, it’s not hard to imagine him raising a stein to the majestic trees that stand there today.