Well Crafted

Well Crafted: From the galleries of Asheville to the backroad studios of world-class artisans, amble along the Blue Ridge Craft Trails to discover the creative spirit of the North Carolina mountains

Today, the Western North Carolina region holds thousands of creators. Many come to learn and hone their craft at arts universities or esteemed craft institutions, such as Penland School of Craft and John C. Campbell Folk School. Others simply come for the creative community itself.

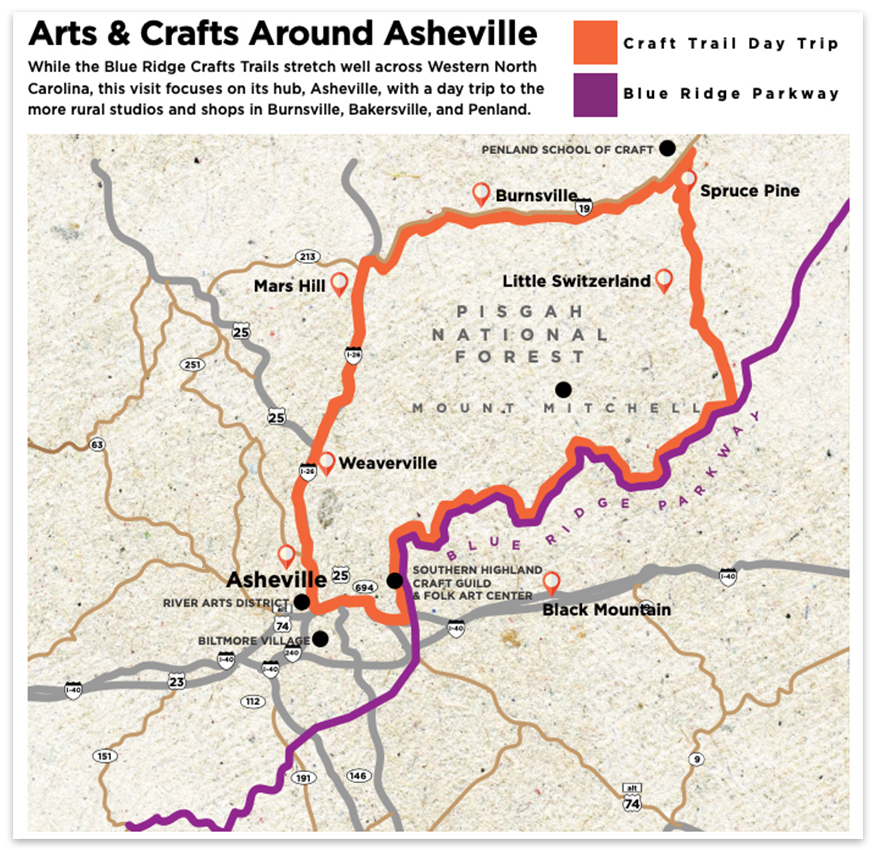

No matter the reason why artists flock here, Western North Carolina is a mecca for art and craft, and there’s never been a better time to tap into this creative nexus. That’s because the Blue Ridge Craft Trails just announced its completion this spring, offering a road map to more than 300 artist studios—many previously inaccessible to the public—as well as galleries and other cultural points of interest all across our 25-county region. The online resource, developed over a four-year period by the Blue Ridge National Heritage Area, lets visitors hone in on their interests and build a customized map and itinerary of stops.

Filled with visions of exploring quaint towns, rural scenic roads, and the tucked-away studios of skilled artisans, I set out to create my own road trip. As Buncombe County marks the completion of the trail and Asheville is the spoke in this giant creative wheel, it seems a fitting place to begin an arts exploration of the Blue Ridge Craft Trails.

Art Central

Located in Asheville’s main square, the Asheville Art Museum is a beacon of creativity, both literally and figuratively. The exterior glows at night, with LED lights shining through a matrix-like pattern. Inside, half of the museum’s collection of 7,000 objects is devoted to preserving and highlighting art from this region. The rest of its holdings, mostly 20th- and 21st-century American works, provide context to this area’s importance and influence in the art world.

From here, it’s easy to set off in almost any direction to discover works by artists and crafters who are painting, sculpting, throwing pots, weaving, carving, and fashioning all manner of materials into handmade creations. In downtown, there’s an art gallery on almost every block. Just south of downtown, Biltmore Village has a smattering of high-end galleries. And further west, in the mile-long River Arts District, around 200 artist studios, plus breweries, bars, and spots to rest and refuel, deserve an entire day of exploration.

Not only are there many spaces in which to see and shop for handmade pieces, but Asheville has many different types of art-filled showrooms. Places like Mountain Made and Appalachian Center for Craft are go-tos for affordable handicrafts (functional pottery, wooden bowls, spoons, and the like). New Morning Gallery in Biltmore Village is perfect for handmade items for the home. Other galleries have a specialty focus, such as handcrafted jewelry at Mora and wearable art at Bellagio, or a focus-driven mission; Noir Collective is a Black-owned shop featuring the work of Black entrepreneurs. And there are even spaces that invite visitors to experience the creative process, including the NC Glass Center, which offers short hands-on workshops as well as multi-week courses in glass. One could easily spend a week or more discovering the galleries and studios in Asheville alone.

With a desire to examine the intersection of fine art and craft, I head to Momentum, where an expertly curated display of contemporary works that defy categorization beckon from behind wall-sized windows spanning the front of the newly renovated 100-year-old building. Across two floors, paintings and sculptures—traditional mediums that fit the mold of fine art—blend with nonfunctional works in clay, wood, metal, glass, and textiles. It feels more like a museum, and the vast majority of works beg the questions, “How in the world was this made and of what material?”

I’m immediately drawn to a pedestal displaying a pair of arms cast in glass cradling a handful of sparkling Swarovski crystals; it’s by John Littleton (Harvey’s son) and his wife, Kate Vogel, who live about an hour north. Nearby, local artist Jeannie Marchand’s monochromatic sculptures framed on the wall are a paradox; it’s solid white clay that’s been folded, fired, and sanded to appear like a cloud-soft blanket. “A lot of the work we show covers material-based traditions celebrated in this area,” says gallery director and owner Jordan Ahlers. But he doesn’t represent artists solely from this region; about half are local. His goal is to “raise the bar and elevate the city and entire region as an arts destination,” he says, and he’s achieving this by showcasing local creators alongside noteworthy and emerging artists from across the country.

Across the street, the Center for Craft is focused on the future of craft. To the general public, it presents as an exhibit space that also occasionally hosts local and virtual programming and hands-on maker workshops. But to craft artists nationwide, the organization is a major think tank and funding body, awarding half a million dollars annually to makers, scholars, and curators pushing the field of craft forward. Because the organization is linked to such a large network of artists, “we can see the emerging trends,” explains executive director Stephanie Moore. “We can see where craft is intersecting with other fields, such as technology.” For visitors to the center, it’s an opportunity to discover just what that future looks like, as most of the exhibits showcase the works of grant and fellowship recipients.

While I’m intrigued by the future of craft, I’m equally interested in its history and heritage. So I head to the Folk Art Center, just east of downtown on the Blue Ridge Parkway, which houses the headquarters for the venerable Southern Highland Craft Guild and Allanstand Craft Shop, the oldest craft shop in America. The juried guild includes more than 900 craftspeople from across nine Appalachian states working in virtually every craft medium. The upstairs holds gallery spaces for permanent and rotating exhibits, while the shop downstairs contains a kaleidoscope of handmade masterpieces—beautiful woven scarves, statement jewelry, handsome wood-turned bowls, ceramic vases and servingware, beeswax candles, and more.

The guild’s origin story is not unlike that of the Blue Ridge Craft Trails. It was born during the rise of mass industrialization and out of a desire to preserve the old-time craft traditions while creating a reliable source of income for makers in this impoverished area of Southern Appalachia. Other cottage industries such as this were cropping up in the region around the same time. John C. Campbell Folk School, Penland School of Craft, Crossnore School, and Berea College just over the mountains in Kentucky—some of the nation’s most recognized craft institutions came out of the craft revival that began here in the early 1900s, and all were created to preserve a cultural tradition while improving the lives of makers and the local economies in which they lived. Those are the very same reasons the Blue Ridge Craft Trails exist today.

Hit the Road

It’s hard to pull away from the vibrancy of Asheville, but it doesn’t take long to stumble into a slower pace about an hour drive north toward Yancey and Mitchell counties, an area that’s rumored to have the highest concentration of crafts artists than anywhere in the country. I’d used the Craft Trails website to create a loose itinerary and timed my day so I could grab a breakfast bite in the picturesque town of Burnsville and still take my time along the Blue Ridge Parkway to return to Asheville.

Named for the pristine waterway that branches and flows in the shadow of the Black Mountains, the highest range in the eastern United States, the Toe River Arts Council is a hub for area crafters. Its gallery in Burnsville is small, but offers a nice overview. Though since I’m on a mission, I head straight toward Micaville and the unincorporated Celo community. I stop by OOAK Art Gallery, full of character and quirk, in an old general store. I drive past Carolina Hemlocks Campground on the banks of the South Toe River, and promise myself I’ll return to swim and sun on the rocks come summer. I stop by the small pottery studio of Pete McWhirter, and learn that he mixes his own red clay, and how his mother had apprenticed under the only potter in the valley and passed on her knowledge to him. At Kenny Pieper’s massive warehouse of a hot shop, I watch as he gathers globs of molten glass and blows and shapes it into perfect glass vessels and goblets. We chat about how craft is one of the largest economic drivers in this area that is otherwise so remote and off the beaten path.

I definitely can’t leave without a visit to Penland School of Craft, which has teachers and alumni that are counted among the most widely collected and revered craft artists living in the US today. While the school’s residencies and fellowships are reserved for emerging and professional artists, anyone can sign up for Penland’s two-week classes, which include room, board, and a fully immersive craft experience. Otherwise, nonstudents can take a self-guided tour of the grounds, though Penland’s gallery is the easiest access point to experience the work that happens here.

Inside, I marvel at a glass chess set and a kinetic sculpture topped by a bird cage, both with price tags in the thousands. Collectors pieces for sure. But there’s also edgy art jewelry, glass-blown barware, and ceramic vases, bowls, and other handmade items that are more accessible. Gallery Director Kathryn Gremley explains that about 50 percent of artists in the community do not have open studios, but “you can find and shop their work here.” I depart empty-handed, but still have one final stop.

Almost within walking distance and on the school’s property is the studio of one of Penland’s most beloved instructors and the unofficial Mayor of Penland: Cynthia Bringle. I greet her as she’s pulling groceries from her truck and I help her inside. She’s now in her early 80s but spry as ever and eager to talk about pottery and show me around. Her studio is enormous, with shelves holding glazes, stacks of books, pots in various stages of firing, and myriad other supplies, since she paints and dabbles in other mediums. She’s been teaching classes at Penland since 1970 and has taken many courses there herself, she explains, pointing out an elegant wooden chair she made in one of them. A small gallery room at the far end is neatly curated with her pottery and paintings and woven works by her twin sister, Edwina Bringle, who’s equally skilled in her craft.

Before leaving, I pick out a pretty light blue- and ochre-glazed mug to take home; it’s signed on the bottom. As I bid Cynthia farewell, I can’t help but feel honored to have had this experience of meeting her. She is, after all, recognized as a North Carolina Living Treasure, one of the state’s highest honors. But it is this emotional connection, not just with the art, but with the maker, that drives a true appreciation for that which is handmade. And that’s exactly the experience on offer along the Blue Ridge Craft Trails.

In the Mountains

Whether you're visiting from out of town or you're a native of Western North Carolina, check out these can't-miss experiences.

■ Check In

It took years to transform an eyesore in the center of downtown into the chic, modern Kimpton Hotel Arras, which is full of commissioned works by local artists. Tours of the artworks are held daily at 4 p.m. The lobby bar and restaurant are excellent and open to the public. Insider Tip: Reserve a room above the fourth floor facing west for sunset views over the city and mountains beyond. hotelarras.com

■ Eat & Drink

At Holeman and Finch, one of downtown’s newest upscale restaurants, the inviting setting is just as intriguing and sophisticated as the menu, which pulls from many area farms as well as the sea. Cured meats and cheeses, snacks, small and large plates, seafood towers and oysters, and expertly-prepared offal present a flavor-filled adventure. holeman-finch-avl.com

In West Asheville, Leo’s House of Thirst, is an intimate den serving up one of the city’s best food and wine experiences. The mostly small-plate menu is great for sharing and every bite is worth savoring. The substantial wine selection is noteworthy, as are knowledgeable servers who are quick to recommend pairings. leosavl.com

■ Get Creative

Visit blueridgeheritage.com to explore the Blue Ridge Craft Trails. The site offers suggested itineraries, or you can build your own. Search by region or interest, and add stops to create a map and itinerary, which you can share with your mobile device for easy navigation. Some artist studios are only open by appointment, so do plan ahead.

It’s easy to explore the River Arts District on your own but a few things to bear in mind: The RAD, as it’s called, is spread out, with more than 200 studios inside 23 former industrial warehouses. It’s best to pick an area to park and walk. There are no official open hours, but you’ll find open studios and galleries almost any time a day. Free trolleys run on the second Saturday, March through September. Find artists, maps, and information on workshops and special events at riverartsdistrict.com.

If exploring the RAD with a knowledgeable guide sounds enticing, Asheville Art Studio Tours offers two-hour guided and customizable studio tours, some which include hands-on art experiences. More at ashevilleartstudiotours.com.

For tons more info to help you plan an art-filled visit to Asheville, including a robust list of galleries and other arts offerings, visit exploreasheville.com.