Unforgettable Rampage

Unforgettable Rampage: Even a century later, the Great Flood of 1916’s watery depths haunt Western North Carolina

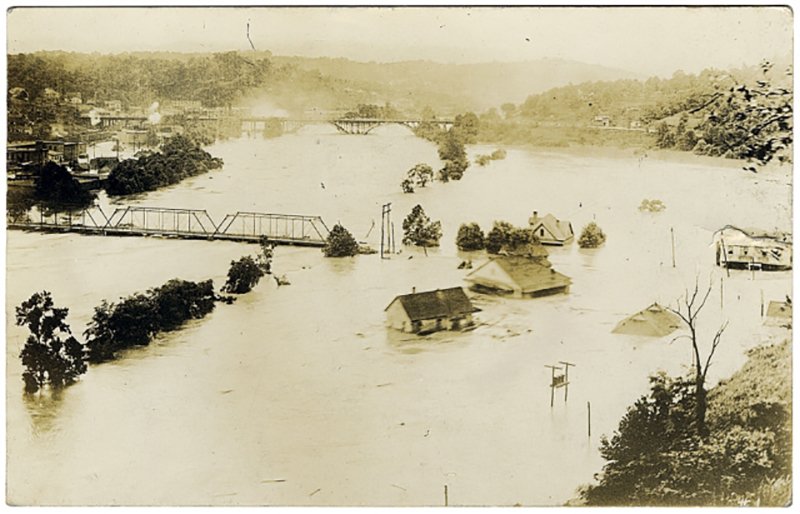

We can witness some of the damage in black and white archival photos, and learn more of it from faded newspaper clips. But it’s still hard to grasp the extent of the cataclysm that was the Great Flood, Western North Carolina’s biggest natural disaster in recorded history.

True, there have been massive gully washers here before and since. Spring rains in 1791 were so heavy they raised floods that Davy Crockett called “the second epistle to Noah’s.” And as recently as September 2004, the one-two punch of hurricanes Frances and Ivan devastated many mountain towns.

But even now, “1916 stands as the year of the river’s chief and unforgettable rampage,” as Wilma Dykeman wrote in her seminal 1955 book, The French Broad. “Those who felt its power then remember something of the wild force that the combined elements of mountains and water can create in this special situation. And they remember its dark beauty too.”

Perfect Storms

Dykeman might have waxed too poetic about the flood’s “beauty,” but she correctly noted that summer storms surging up from points south “have turned the French Broad, on occasion, into a veritable tidal wave of death and devastation.”

The most notorious occasion fell in July of 1916, when waves of record-breaking precipitation piled up. The first week of the month, the remnants of a Gulf Coast hurricane soaked WNC, and the rains never seemed to stop after that. Then, on July 16, a hurricane from the Atlantic brought an additional onslaught. At one local weather station, 22 inches of rain were recorded in 24 hours.

At the time, flood stage on the French Broad was marked at four feet over the norm; the combined storms pushed the waters to a crest of more than 23 feet. The river, which averaged 380 feet in width, swelled to more than four times that span. As riverside residents began to seek higher ground or, in some cases, drown, houses on waterlogged mountainsides cascaded down in landslides. In several interviews after the flood, that’s what people emphasized: the sickening sound of a home sliding down a ridge, sometimes with a family inside it.

Devastation

Like other epic floods, WNC’s became ingrained in local history, and it lives as a shock to the region’s system that reverberates on and on.

“Asheville today staggers under the greatest catastrophe it has ever known,” the Asheville Citizen recorded on July 17, 1916, in an issue prepared without electricity and phone and telegraph connections. Key parts of the town were laid waste as the railroad district and much of Biltmore Village were subsumed and transit routes for people and goods were interrupted. An editorial in the newspaper lamented the fate of riverside businessmen, “who in many cases have seen the investments of a lifetime swept away.”

The catastrophe also rocked communities in South Carolina, Tennessee, Virginia, and West Virginia, but bearing the brunt was North Carolina, and especially Western North Carolina. Exactly how much loss did the flood wreak in the mountains? Contemporary accounts suggest grim numbers: 50 to 80 people dead with hundreds gravely injured, thousands of houses destroyed, and untold businesses suddenly washed out. Hundreds of miles of railroads, a key means of moving people and goods, were disabled. When the waters finally receded, the financial damages were estimated at some $22 million—the equivalent of almost half a billion dollars today.

And while it’s sometimes referred to as Asheville’s Great Flood, the disaster was hardly limited to WNC’s largest municipality. In Marshall, Main Street was deluged with eight-foot swells and 58 homes were destroyed. In Henderson County, several main roads disappeared, with the county seat, Hendersonville, accessible only by boat. Rutherford County provided a grim newspaper headline: “Village of Chimney Rock Reported Gone.” The greatest single loss of life occurred in Gaston County, where 10 railroad workers drowned after a failed effort to stabilize a trestle on the Catawba River.

Certainly, no community had a monopoly on the destruction. Throughout the region, textile and furniture mills, bridges, dams, and roads were washed into oblivion, while mountain crops took a beating, raising the specter of starvation that was addressed in earnest but only in part by local charity drives and state and federal aid. The mountain practice of canning food for the coming year was one of the few saving graces.

The broad scale of the devastation left behind deeply personal stories that seared the area for generations. In one especially tragic example in Asheville, a few nurses from Biltmore Hospital and a family from Biltmore Village got picked off, one by one, by the rising waters as they clung to the upper reaches of a tree. Hundreds of neighbors looked on helplessly. After valiant swimmers failed, rescuers in a boat ultimately saved the sole survivor, a young girl. Hours earlier, her father, a superintendent at the Biltmore Estate, had used his coat to secure her to a branch, only to succumb to fatigue and slip away to his death.

A short distance away, residents of the Glen Rock Hotel were stranded by the waters. Two local men volunteered to deliver food and water to them, via a boat, but it capsized amidst the violent current, and they drowned as well.

Lessons & Warnings

On July 20, as the waters subsided, an editorial in the Asheville Citizen decried the town’s lack of planning for such an eventuality. “Had Asheville anticipated the flood,” the newspaper said, “she would have been prepared against it by having her river banks in the industrial district planted with trees … and the piers of the bridges in this vicinity would have been far enough apart and the arches high enough to allow the free passage of wreckage and debris.” What’s more, the newspaper campaigned against artificial lakes, given the devastation downstream from burst dams.

Even today, 100 years later, the Great Flood remains an unavoidable reference point for urban planners, emergency managers, residents, and environmental advocates who want to mitigate the impact of future disasters. That is clear from the work of the Center for Cultural Preservation, a Hendersonville-based nonprofit that collected stories from descendants of victims and produced a new documentary on the flood, Come Hell or High Water, that debuted in June.

“So many of the mountain elders we talked to had connections to the flood,” reports David Weintraub, director of the center and the film. “When something like this happens, families pass the stories on and on and on, and they’re powerful,” he says.

A key lesson learned, he adds, is that while we’re accustomed to thinking of flood damages coming from below, in the form of rising waters, “some of the greatest devastation came from above, with the landslides on many steep slopes.” Building on such peaks, he counsels, can remain risky today, even with modern improvements in construction. Landslides stemming from the September 2004 storms were a testament to that, he says.

“How can we apply our history to our present and future?” Weintraub asks. “We are building on some of the same scars that were caused by the 1916 floods. I hope we can better understand how to live with nature. We live in a flood-prone area. The question isn’t if it will happen again, but when.”

GREAT FLOOD REMEMBRANCES

An Unforgettable Rampage

On July 13 at noon, WNC magazine’s Jon Elliston will give a free multimedia presentation on the flood at Pack Memorial Library in Asheville; meanwhile, a state historical exhibit on the flood continues at the library through July 15. (828) 250-4740 www.ncroom.buncombecounty.org

Come Hell or High Water

Screenings of the new documentary by the Center for Cultural Preservation will take place throughout WNC this summer. Visit www.saveculture.org for details.

So Great the Devastation

On July 16 starting at 10 a.m., a free, daylong centennial commemoration at A-B Tech in Asheville will feature the dedication of a new state historical marker, speakers, and performances. www.abtech.edu