Trolley Town

Trolley Town: The golden age of streetcars jump-started Asheville and led the way for mass transit in North Carolina

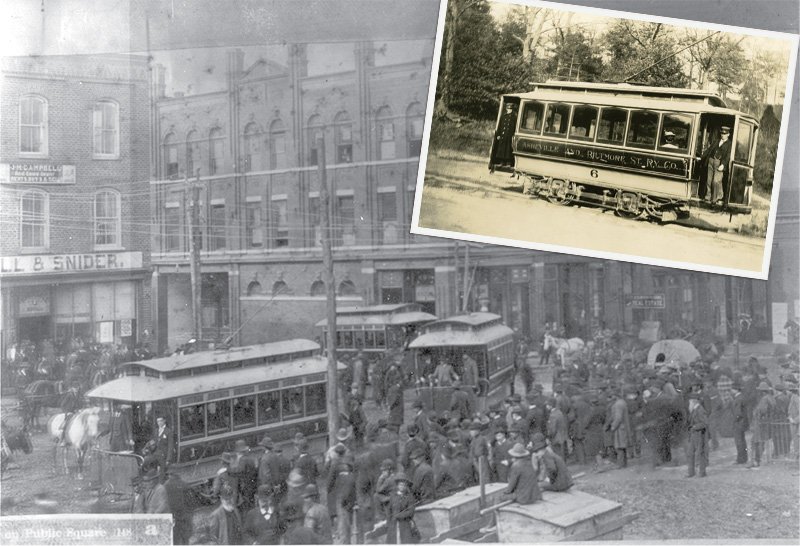

Trolley-ho! Ashevilleans packed downtown streets to see the first run of the city’s electric streetcars in February 1889.

Many folks of local stature, and anyone who could steal away from workaday obligations, thronged to Asheville’s Main Street the afternoon of February 6, 1889. Most traveled via their own feet or steed to see a new way of getting around a hilly town that was outgrowing its horses and buggies.

The crowd dazzled at Asheville’s initial fleet of electric streetcars, which offered capacity, comfort, and consistency unthinkable for horse-drawn vessels while costing just a nickel per ride. And for the first time, they heard the grind of the gears, squeak of the brakes, and churning clatter of cars that would become part of the local soundscape for decades to come.

There were just three trolley cars, but they were enough to sound the celebration. “A brilliant opening,” the Asheville Citizen newspaper declared. Not only had “all went merry as a marriage bell,” the arrival of the streetcar meant that “no happier community than ours is to be found in America.” By years end, five more cars had been added, and there were many more to come.

No simple town

In fact, Asheville was the first city in North Carolina to establish an electric streetcar system, while the towns then known as Winston and Salem were quick to follow, with Charlotte and Wilmington soon thereafter. The trolleys revolutionized transit in Asheville: with efficient electric power connecting to the cars via wires over the tracks, they could suddenly shuttle much of the city’s rapidly growing population on the cheap, which proved to be a huge boon to the local economy and put Asheville on the proverbial map.

With mass local transportation suddenly available, it’s hard to overstate how much trolleys changed the town. “A new era was born,” the three authors of Trolleys in the Land of Sky noted in their encyclopedic 2000 publication, which is rare but available at several local libraries. “No longer would Asheville be a simple mountain town, sparked only by health seekers and the wealthy fashionable of the East.”

The Asheville Citizen captured the electrified nature of the times in an editorial, titled “The Lightning Harnessed,” that heralded a new age of “quick transit.” The cars were capable of traversing from Biltmore’s train station to the heart of downtown in a mere 10 minutes, a pace previously unimaginable.

The rail system “marks the beginning of a new era in the development, improvement and prosperity of this progressive city,” the paper wrote. Electricity, “the most inscrutable and awe-inspiring of all the secret forces of nature, is now harnessed in the service of the citizens of Asheville. … We welcome this manifestation of this power in our midst.”

“The streetcars ground into the square from every portion of the compass and halted briefly like wound toys.”

—Thomas Wolfe in his 1904 short story “The Lost Boy”

After the wonder subsided, streetcars became a staple of Asheville life. The companies that owned them competed, morphed, grew and shrunk, and came and went. But the basic service rarely changed: for a minimal fee, almost anyone could hop across town on a regular schedule—as often as eight times per hour—with convenient stops along the way. Packed into the cars, locals shared news, gossip, tips, gripes, and dreams. What’s more, the conveyance was a tourist draw that invigorated Asheville’s reputation as a must-visit destination.

Thomas Wolfe recounted, as only he could, a typical downtown scene in his short story “The Lost Boy,” set in 1904: “The streetcars ground into the square from every portion of the compass and halted briefly like wound toys in their old familiar quarterly-hour formula.”

Little about Asheville’s trolleys, though, was static: the system reached three million passenger rides a year in 1907, the top ridership in the state. At its peak in 1915, it conveyed Ashevilleans and visitors on 43 cars along 18 miles of track. Key routes extended to West Asheville and Weaverville, with spurs to destinations like Riverside Park, the Grove Park Inn, and Sunset Mountain.

Ups and downs

True, there were bumps along the way: a couple of labor strikes that halted service for a bit until wages were raised, the occasional derailment, and a few serious accidents.

One of the worst happened in May of 1922, when two cars navigating the Weaverville line from opposite directions collided head-to-head, killing conductor A.L. Ballew. A worker from Ballew’s car who survived that accident, Winfield Vehaun, penned a gospel tune about the experience, “The Time is Near,” that found its way into hymnals.

Often, the problems were more pedestrian. As the Asheville Citizen noted in 1902, the system was bedeviled by “promiscuous expectoration”—that is, (mostly) men sloppily spitting their tobacco juice where it didn’t belong. But almost all of the time, there was no safer, cheaper, cleaner, or better way to get from point A to point B.

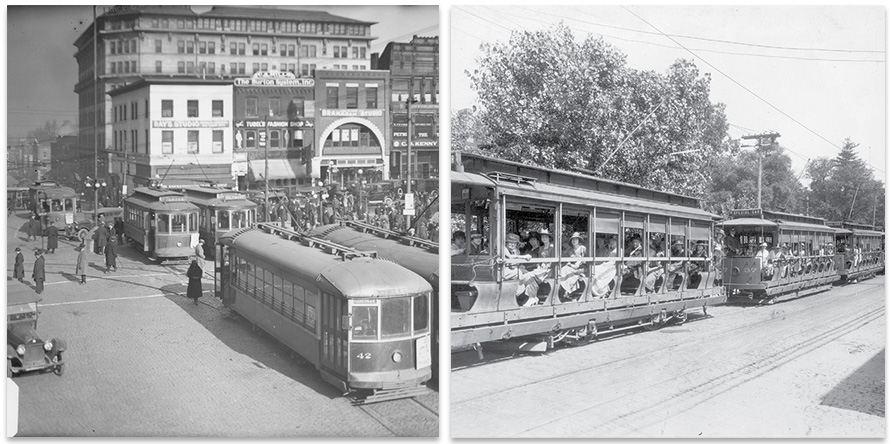

(Left) A typical street scene in early 1920s Asheville; (Right) A string of streetcars takes teachers to the Asheville Normal School in 1919.

Last stop

For all they did for Asheville, electric trolleys could serve for only so long, and just as they had replaced older forms of transportation, better options ultimately came along. Forty-five years after the streetcars first rumbled through town, the rise of the automobile and the passenger bus made them obsolete.

The final rides happened on September 7, 1934, when seven cars made a ceremonial and philanthropic journey from Pritchard Park to the end of the West Asheville line. The fares that day were waived, but every penny donated went to the Asheville Orthopedic Home, then fighting the scourge of polio.

It was a bittersweet send-off, to be sure. As the Asheville Citizen noted: “Although the general motif was gay, there was an undercurrent of sadness among many of the passengers at the passing of the familiar streetcars which had served the city so long.”

Still, these steadfast craft hadn’t quite outlived their usefulness. Many of them were parked and repurposed at Fortune’s Street Car Tourist Camp, a vacation destination on a stretch of Hendersonville Road. One went on to become part of a house. And they all inspired the various sightseeing bus tours, many of them trolley-themed, that have curried visitors and locals around the city in recent years, plying their way up, down, and around streets where some of the trolley tracks remain, just beneath the surface.