Swannanoa’s Superspy

Swannanoa’s Superspy: A trove of declassified documents unveils Carl Duckett’s unlikely journey from small-town roots to top CIA official

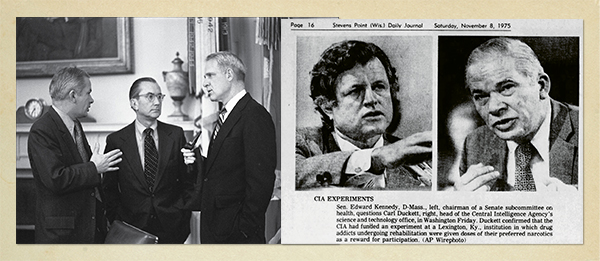

Duckett, who usually avoided the limelight, was photographed at the White House while receiving an award from President Ford in 1974.

Today, the threat of a North Korean missile strike against the United States is increasingly grabbing headlines. But few people know of the crucial role that Western North Carolina’s own Carl Ernest Duckett long played in crafting strategies for warding off—and if necessary, winning—a nuclear war, along with the story of his improbable rise in the US intelligence community.

Through it all, Duckett shied from the spotlight and sidestepped some of the CIA’s greatest controversies. Serving in the shadows, he rarely spoke of his decades of spy craft, and even 25 years after his death, parts of what he did remain secret. Over time, though, a growing collection of declassified records has revealed his role as a key player in high-tech espionage at the height of the Cold War, which he quietly helped win.

Humble Beginnings

No one could have predicted Duckett’s career in the global spy wars, but it was clear early on that he possessed intellectual gifts and plenty of drive. Born the fourth of seven children to a hard-working but poor Buncombe County family in 1923, he excelled in high school, as local newspaper reports collected by the Swannanoa Valley Museum & History Center show.

Duckett was an honor student, and in 1937, he won a pig from Sears Roebuck in an essay contest. Then, he proved persuasive in matches for Swannanoa High School’s debate team and was elected its leader.

Off the Record: Even as many papers documenting Duckett’s CIA work have been declassified, others, such as the above portion of a September 1974 National Security Council meeting about Soviet nuclear capabilities, remain secret even today.

Duckett’s father, William, had done well at jobs at the local textile plant Beacon Manufacturing Co. and a railroad line. But after high school, Carl couldn’t afford college and saw few options before him. He took a grocery store gig then signed up to work at a textile mill. One of his secret CIA bios, written decades later, recounted what happened next.

“As he rode to the mill he became lost is his own thoughts,” the bio says. “The more he pondered, the more he realized that if he entered the mill, he would probably never expand his education or his horizons. It was 25 miles back to his home but he left the bus, walked home, and turned to a different future.”

To War

World War II put Duckett’s path to the future in high gear. In the spring of 1942, he excelled in a six-month US Army crash course for electronics technicians. An intensive training at Johns Hopkins University followed, and then, at only 20, Duckett helped the Westinghouse corporation develop a radar system and was dispatched to France soon after D-Day to help run some of the earliest radar units. After that, he returned stateside to help design the Army’s new generation of missiles.

Even as Duckett’s star rose in the national security firmament, the fact remained that he’d never completed a college degree. For him, it was an unnecessary merit, as later years would prove, but the lack of a formal higher education would dog him nonetheless.

Secret Agent Man

In the early 1960s, the leadership of the Central Intelligence Agency was stocked with elites from Ivy League schools. Without a blue blood pedigree, Duckett bucked the trend.

After racking up a roster of increasingly important military assignments, Duckett became a logical pick for a role in the intelligence community’s scientific vanguard. In 1963, the CIA recruited him, and three years later appointed him deputy director for science and technology, making him the agency’s third-ranking official, a position he maintained for a fateful decade.

The agency slapped Duckett with urgent tasks: Figure out the Soviet Union’s actual capacity for nuclear war. Assess and improve the US’s as well. First and foremost, guide our most scientific and sensitive operations into the new technological age, when mechanical eyes in the sky will supersede human spying on the ground.

From CIA headquarters, Duckett ran secret ops around the globe—U-2 flights over the Soviet Union and China, and then ones by even more sophisticated reconnaissance planes and satellites; massive electronic eavesdropping efforts to collect intel on adversaries’ communications and military activities; and one of the most audacious spy gambits in history—a mostly failed, supersecret CIA plot to raise a wrecked Soviet submarine from its resting place three miles below the surface of the Pacific Ocean in 1974.

Halls of Power: Duckett participates in a briefing at the White House in March 1975 with CIA Director William Colby (center) and Secretary of Defense James Schlesinger (right). Later the same year, Duckett would make a rare public appearance, testifying to a Senate committee about revelations that the CIA had conducted extensive secret drug tests.

Then there was the really edgy stuff: the CIA’s experiments with drugs for interrogations and biological warfare, a psychic spying program, and attempts to develop spy tools worthy of James Bond—exploding pens and the like. It was a strange time, but even as the agency’s worst embarrassments from the era were aired in congressional investigations, Duckett mostly escaped exposure (save for a dustup over his lack of candor to congressional investors about the CIA’s relationship with a major Thai drug trafficker).

Perhaps that’s because he was one of the CIA’s greatest back-room dealers. Many of the declassified records that mention Duckett review his outreach to Congress for funding of the agency’s most expensive projects of the time. They reveal his knack for summarizing complex intelligence topics in relatable terms, and he had a reputation as a straight shooter with an uncommon understanding of the science behind all of the subterfuge. Henry Kissinger was prone to calling Duckett “professor” in national security meetings during the Nixon and Ford administrations.

Passed over?

From the available records, it’s impossible to tell exactly why Duckett left the CIA in 1976. Some “accomplishments attributable to Mr. Duckett’s leadership in the field of science and technology cannot be discussed freely,” the CIA noted internally as he was about to retire. It is clear that Duckett and the CIA’s then-director, George H.W. Bush, did not get along.

Some reporters and historians have suggested that Duckett was miffed that he was never placed in line to lead the CIA. He thought he’d done the work and was the person for the job, academic credentials be damned—and some of the recently declassified records do indicate that top officials took note of his unconventional education and considered it a potential barrier to advancement.

After Duckett left the CIA, he led a technology consulting firm and granted a few interviews while mostly staying mum about his classified life. He died in 1992 in Virginia, at age 69.

Nowadays, history is catching up with him as more documents are declassified. One of them, an award nomination penned by the CIA late in Duckett’s government career, called his work “essential to the security and welfare of the United States and the free nations of the world.”