Steamboat Dream

Steamboat Dream: The Mountain Lily’s short but storied run on the French Broad River might never end

Maiden Voyage? One of the few archival photos of the Mountain Lily appears to show preparations for its first outing in August 1881. Hopes for the steamboat ran as high as the challenges it faced.

Can you imagine witnessing a steamboat gently plying its way down the French Broad River? Well, some people didn’t have to: they saw it with their very eyes.

It’s quite understandable why folks would want to take a canoe, kayak, tube, or fishing boat down one of the oldest rivers in the world, witnessing altitudes, channels, and vistas that have garnered praise from the beginning of recorded local history. But a steamboat? The vessel accustomed to vaster waters than the French Broad’s shallows? It took a special kind of moxie, and an audacious gamble, to conceive the idea and put it in motion.

MAN WITH A PLAN

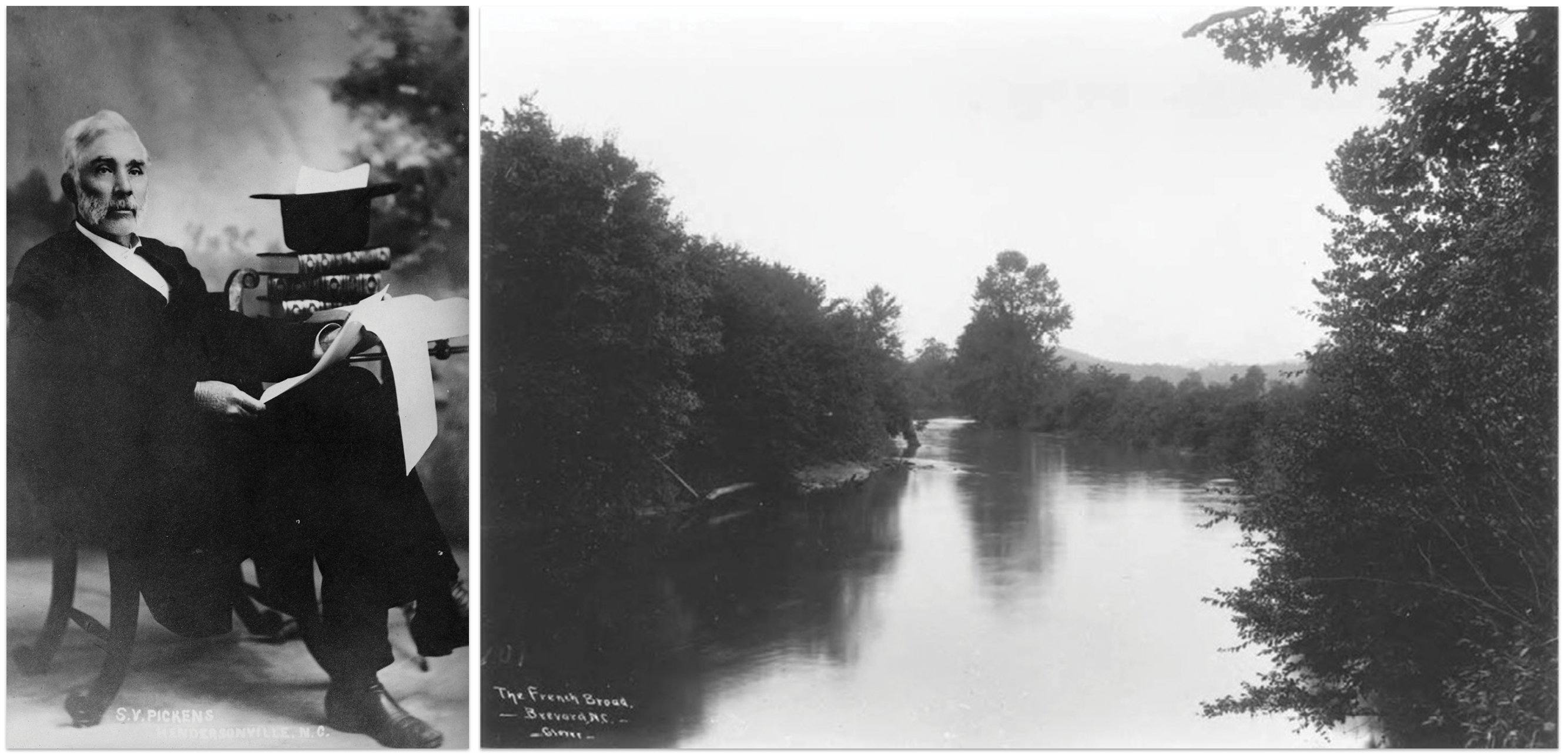

Time was, there were few good roads, and no rail lines, connecting Western North Carolina hubs like Brevard, Hendersonville, and Asheville. So while the desire to transit people and goods among those towns was strong, the journey was arduous and slow. Sydney Vance Pickens, a Confederate veteran, Buncombe County native, and Henderson County civic leader, decided to do something about it.

Normally, Pickens wasn’t the kind of person readily accused of hatching madcap schemes. In his illustrious career, he founded what became the North Carolina Bar Association, created Hendersonville’s trolley system, and served as the town’s mayor (while remaining, to his discredit, an ardent white supremacist). In 1880, Pickens and partners incorporated the French Broad Steamboat Company, “for the purpose of acquiring, building, keeping and running a steamboat on the French Broad River,” according to the Congressional Record.

Take the steamboat down to Asheville,

Hear some mountain music there.

Take a ride on the Mountain Lily,

The highest steamboat anywhere.

—David Holt, “Goodbye, Goodbye”

The idea prompted no shortage of skepticism, but Pickens succeeded in lobbying influential friends in the US Congress to support the endeavor with federal funds. In short order, army engineers went to work dredging stretches of the river, blasting out bedrock, and building jetties, all in the hopes of making his boat float. (It took some legislative debate, to be sure: one Ohio Senator carped that the French Broad was hardly fit for catfish to navigate.)

(Left) Prime Mover Sydney Vance Pickens, the key player behind the Mountain Lily enterprise, had friends in high places that propelled his venture; (Right) Still Waters The French Broad looks much the same today as when the Mountain Lily made its brief trips in the 1880s.

With that largesse secured, Pickens commissioned the building of a steamboat, the one and only Mountain Lily. In late-1800s Western North Carolina, its dimensions and capacity were nothing short of stunning. The boat was 90 feet long and straddled by two paddle wheels, each powered by a 12-horsepower steam engine. Its two decks could carry 100 people, it was hoped, without sinking the structure into the riverbed. Pickens had it painted a gleaming white, with green trim, and he quickly sold out of shares to finance the venture.

In August of 1881, the Mountain Lily made its maiden voyage, with gussied up local notables aboard and hundreds of mountain folks lining the riverside to witness the spectacle. Had Pickens’ steamboat dream become a reality?

ROUGH SAILING

At first, the pomp and circumstance—including the ritual smashing of a champagne bottle on the Mountain Lily’s hull and boisterous tunes by a brass band—seemed to signal that something transformative had come to WNC’s travel and leisure set. The initial journey proved brief but wondrous. The boat didn’t sink or run aground, though it didn’t travel very far from its birth in Horse Shoe.

It proved a thrilling jaunt for one local child; she rode aboard, and shared her memories with The Brevard News in 1929. “On the maiden trip,” she said, “all Brevard and vicinity took a holiday, and most of them took a ride on the steamer.”

The development sparked florid prose from the era’s newspapers. “This will be the highest steam navigation in the world and one of the chief attractions the land of sunsets offers to tourists during the summer months,” Raleigh’s News and Observer predicted.

“The Mountain Lily still plies the limpid waters of the French Broad,” Hendersonville’s Independent Herald announced a month after the launch, “making pleasant tours up and down the river, where scenery unsurpassed in grandeur greets the eye from romantic mountains and shady cliffs.”

Still Here A miniature model of the Mountain Lily, created by Knox Cowell, can be found at the Henderson County Heritage Museum.

But Pickens’ gambit ultimately proved a bridge too far, as local historian Terry Ruscin noted in his 2016 book A History of Transportation in Western North Carolina. “The shallowness of the Broad hindered the ship’s navigation,” on the one hand. “Additional setbacks included unpredictable variations in the river’s flow, extreme drought, low-hung bridges, and obstacles presented by logjams, beavers, and muskrats.”

During a particularly dry summer, mules were pressed into service more than once to drag the Mountain Lily back to its puddle of a port. Instead of long-haul trips between Brevard and Asheville, as Ruscin noted, the boat settled for shorter floating parties, with “each of them not nearly as successful as Pickens had planned.”

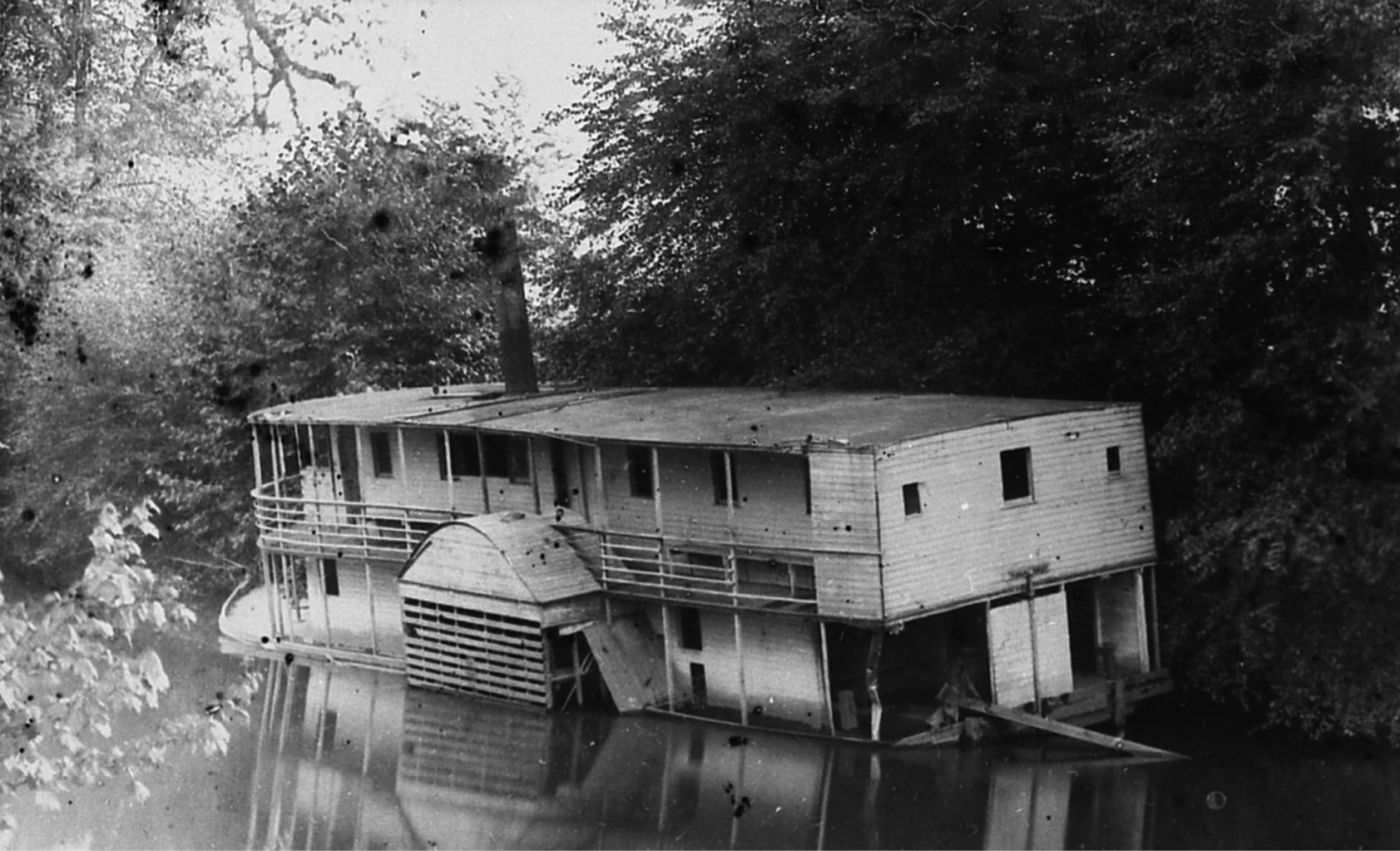

The Mountain Lily’s bold experiment ran aground in 1884, when it literally ran aground, thanks to the wily French Broad. Torrential rains swelled the river, pulling the boat from its moorings. It drifted a bit, passengerless on its last voyage, then got stuck in the muck on the riverside near the community of Mills River. There, it sat for years, and was slowly dismantled and salvaged. Its boards went to build a local church that was later rebuilt; its engines were repurposed for sawmills now long gone. Its huge, clanging bell—now about 140 years old—is said to still sit on private property in Henderson County.

FLOATING ON

And there the Mountain Lily’s story might have ended, were it not such a compelling one. For decades, those locals who had seen and/or ridden it enshrined the tale in mountain lore, their accounts growing more grand and varied over time. An Asheville historian, Sarah Upchurch, would later remark that “there are as many versions of the story of the Mountain Lily as there have been writers to tell them.”

End of the Line The Mountain Lily at her resting place, a curve in the French Broad near Mills River, where she settled in 1884. In the ensuing years, her lumber, engines, and bell were salvaged.

One thing remains certain: the Mountain Lily’s saga will last longer than its halting runs on the river, at least in popular culture. In 1973, poet Robert Morgan addressed Pickens’ folly in “Real and Ethereal,” part of which spoke to the iconic photograph of the stranded steamboat:

There’s a picture somewhere made

of the sidewheeler stranded on mud

near the bend at Arden,

swaybacked and listing, stack

tilted like a gun.

Not so much a floating palace

as a tenement or bunkhouse

on a barge.

David Holt’s aforementioned ditty about the Mountain Lily, “Goodbye, Goodbye,” was recorded for his classic 1985 album Reel & Rock and retains the sprightly optimism of the boat’s happier days.

And the most elaborate artistic salute to the Mountain Lily thus far covered both the triumph and the tragedy. The Ballad of the Mountain Lily musical debuted at the pavilion at Asheville’s Recreation Park in 1982. It first played during an annual celebration, French Broad River Week, that helped build the present-day enthusiasm for the river’s vitality, and later saw at least one more performance.

In the short production, local volunteers gave a spirited show that might have made Pickens proud, if not a little uncomfortable. Working from a script by Sarah Upchurch, they closed out with lyrics like these:

Perhaps it’s not silly

To call me a Lily,

’Cause planted in sand I now lie

My flag is all droopy,

My poop deck’s all poopy,

A wreck of a steamboat am I!