Siren Shrub

Siren Shrub: The curious appeal and dangerous past of mountain laurel

It’s not as showy as its cousin, rhododendron, but mountain laurel, with narrower leaves and prim clusters of pastel blossoms, is deceptively alluring. An evergreen that thrives in high elevations and acidic soil, the native Western North Carolina species is also related to the classic bay laurel, whose recognizable leaves were once woven into Greek head wreaths.

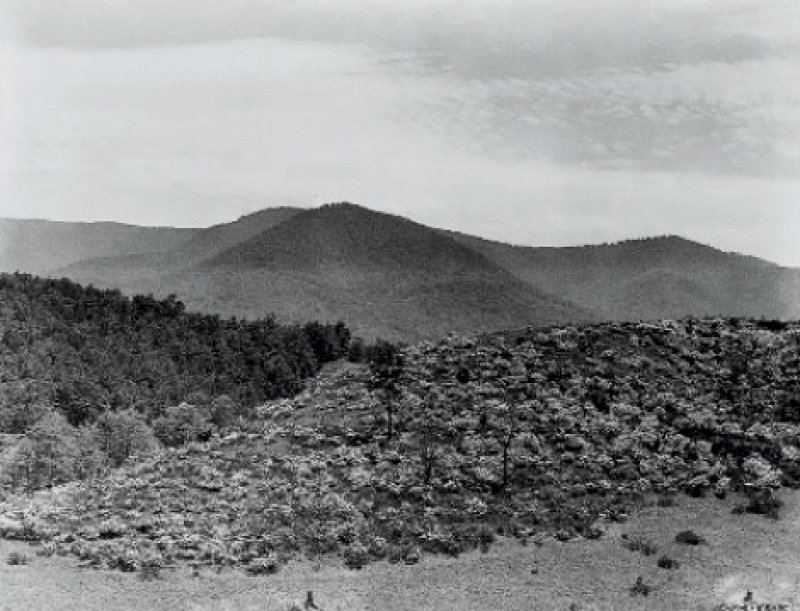

As bay exemplifies ancient Greece, mountain laurel is an icon of Southern Appalachia. In the days before herbicides, the tall shrub smothered mountain balds, contributing to the area’s geographic isolation. Beneath those delicate flowers and dark leaves, its gnarled branches were so dense that wanderers who tried to penetrate the maze were sometimes lost forever—or so the legend goes.

In fact, this complex botanical, its small blooms as crisp and round as china teacups, has produced one of the more evocative terms in nature’s nomenclature: “laurel hell.” A two-page entry in Michael B. Montgomery and Joseph S. Hall’s encyclopedic Dictionary of Smoky Mountain English cites several historic texts containing the phrase, including one from Horace Kephart’s classic 1913 travelogue Our Southern Highlanders.

“A ‘hell’ or ‘slick’ or ‘woolly-headed’ or ‘yaller patch’ is a thicket of mountain laurel... impassable save where the bears have bored out trails,” wrote Kephart.

Montgomery and Hall note that a few especially formidable thickets were named for the unfortunate men who were swallowed by them: among others are Huggins’ Hell and Jeffrey’s Hell, located in the Great Smoky Mountains.

Further illuminating the shrub’s dark side, North Carolina Arboretum director of horticulture Alison Arnold reveals that mountain laurel is deadly if eaten by animals. She describes it as a species that sounds as ornery as some of the early mountaineers who attempted to conquer it: “It’s slow growing and hard to cultivate; a plant with a lot of peculiarities,” says Arnold. “It doesn’t flower with the same abundance every year...but it does tend to thrive in some very tough places.”

Mountain laurel generally blooms in May, and by the time the flowers peak in June, laurel hells actually look quite heavenly and innocent. A great time and place to catch a glimpse of these siren beauties is during late spring when the shrub flowers profusely in the appropriately named Pink Beds at the Cradle of Forestry. Just don’t stray too far from the trail.