Sengin' Deep

Sengin' Deep: Author Luke Manget unearths the history of ginseng cultivation in the mountains and beyond

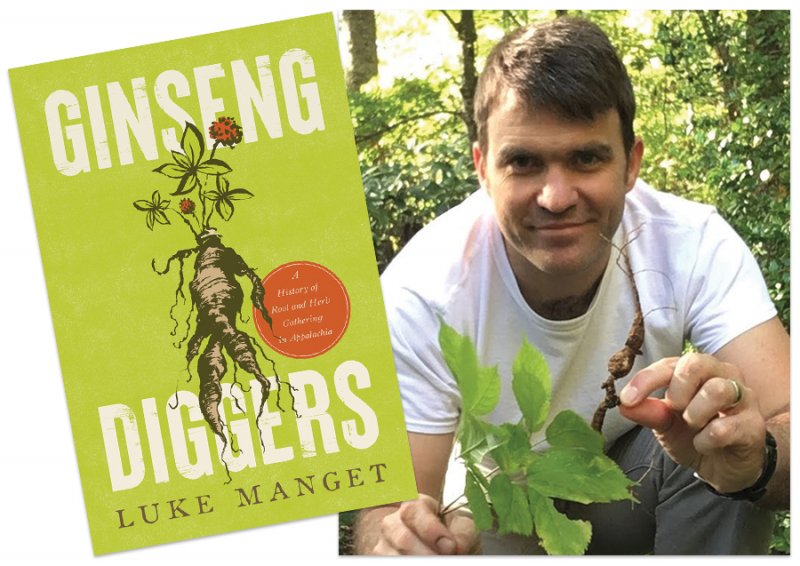

Editor’s note: All jokes aside, Luke Manget really digs ginseng. An assistant professor of history at Dalton State College in Georgia, he’s just authored his first book, Ginseng Diggers: A History of Root and Herb Gathering in Appalachia. Here he reveals some of his findings and suggests new ways of thinking about an ancient mountain tradition.

Ginseng Diggers is the first book to unearth the unique relationship between the Appalachian region and the global trade of medicinal plants. Talk about how your book breaks new ground.

Few scholars have investigated the supply chains of the pharmaceutical industry in the 19th century, and my research has found that Appalachian roots and herbs played an important role in pushing the pharmaceutical industry to use more medicinal plants native to North America in drug production. … With its origins in the 1840s, the American pharmaceutical industry grew fast after the Civil War, and while much of the growth centered around the production of imported plants and minerals, there was sizeable growth in medicines produced with native plants, especially among those medicines marketed directly to consumers, the so-called patent medicines.

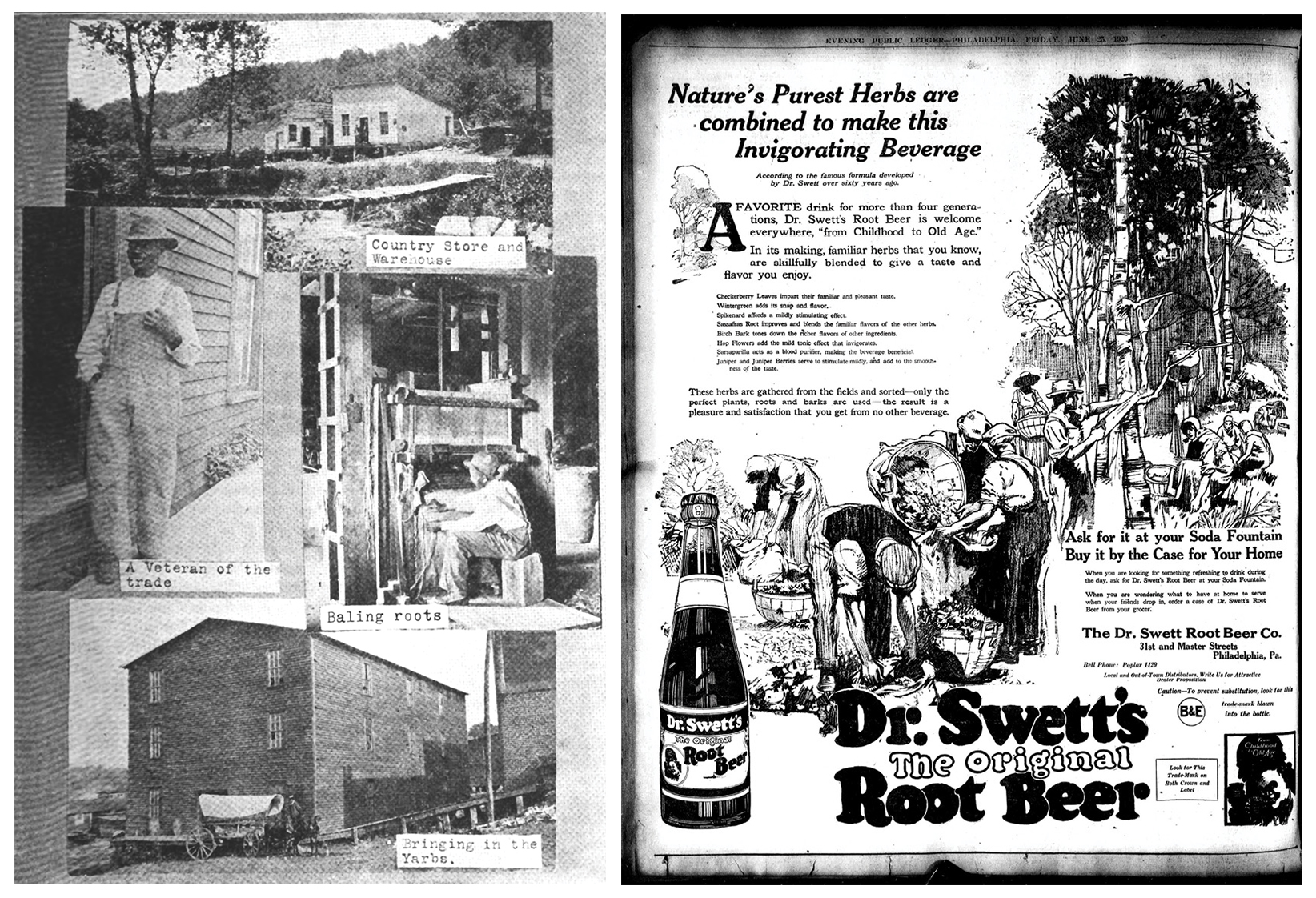

Appalachian people were deeply enmeshed in these supply chains. They harvested these plants from the forest commons and traded them at their country stores, which in turn sold them to “botanical drug houses” in the piedmont. Some of these firms became the largest of their kind in the nation, if not the world. Gathering roots and herbs for these markets provided mountain communities with a significant source of income, and they engaged in these markets largely on their own terms, using their time and labor as they saw fit to obtain extra purchasing power in the consumer economy. In this way, the pharmaceutical industry empowered Appalachian communities in the 19th and early 20th centuries.

Your 10 years of research involves one of the most extensive uses of country store records to date in Appalachia, examining the account books and day books of some 34 different establishments located in 13 different repositories. Tell us more about this uncovering.

ECONOMIC ROOTS - For thousands of mountain farmers, patent medicines, refreshments, and a range of other products developed into a vital source of income.

Finding the sources to uncover the identities of these ginseng diggers proved to be a challenge. After exhausting the digitized newspaper databases, I had reached a dead end and felt that if I was going to discover just who these ginseng diggers were I would have to get beyond the published accounts of outsiders. I had a hunch that if as much ginseng was being bartered through the country stores as the newspapers claimed, it would appear somewhere in their business records. So I began looking at random country store ledgers from the 1870s. At first, I had little luck, and about the time I had decided to find another dissertation topic, I struck green gold. In the crumbling, yellowed pages of store ledgers from the Wilkesboro [NC] merchant, Calvin J. Cowles, I found page after page filled with ginseng, mayapple, blood root, and other roots and herbs. Emboldened by this find, I began charting research trips across the region, from Kentucky and West Virginia to North Carolina, to explore the holdings of university and state archives, as well as old country stores and local historical museums.

How does the history of ginseng and root digging inform our understanding of the commodification of Appalachia?

The history of root digging and herb gathering reminds us that the rural society that developed in Appalachia was shaped by both a diverse and abundant ecological base and the ability of all community members to access that ecological base. Access to the commons was essential for all community members—especially landless tenants, sharecroppers, unemployed miners, and young farm families just starting out on their own—to obtain the resources necessary to sustain their households.

This fact bears repeating: the sharing of the land helped sustain agrarian Appalachian communities. And by “communities,” I am referring to ecological communities that included both human and non-human nature. The triracial culture that developed around the commons enabled an ecological continuity across the landscape, and this continuity was disrupted when the land was cordoned off according to arbitrary boundaries. As trees and land were commodified, property lines hardened and the landscape was fragmented, accelerating socioecological change. The effective enclosure of these commons—whether due to new laws, fungal disease, fencing, changing markets, or deforestation—is an important factor in why mountain people lost their independence. By reclaiming this history, I am, in a way, reclaiming the commons as an important part of the American heritage.

GOOD FOR WHAT AILS YOU - Frequently foraged medicinal plants have included bloodroot, above left, pinkroot, inset, and American ginseng, middle. Far right, a Haywood County farmer with his ginseng crop.

How did ginseng gathering in Appalachia open up trade relations between the United States and China?

By the late-18th century, American ginseng had become an important global commodity unlike any other. A native of eastern North America with concentrated populations in the Appalachian Mountains, this species of ginseng was genetically similar enough to the highly esteemed Asian Ginseng that Chinese consumers found it to be a ready substitute. Increasing Chinese demand stimulated a series of ginseng booms that expanded down the Appalachian spine from the 1780s through the 1830s as Euro-Americans and Native Americans scoured the forests to find it.

Indeed, it is not too much of a stretch to say that ginseng opened trade relations between the United States and China: Appalachian ginseng comprised the primary cargo of the Empress of China, the first ship to sail from the U.S. to China. From then until the late 20th century, Chinese demand was the sole driver of the American ginseng trade. This fact punctures the myth that Appalachia was an isolated backwater cut off from the currents of the global economy. From this perspective, Appalachia was responsible for establishing perhaps the most important global trade relationship of the 21st century.