In Search of Gold

In Search of Gold: Following Hernando de Soto’s historic–and devastating–legacy through the South

On May 21, 1540, Hernando de Soto, with most of his 620 conquistadors and the female chief of a Native American tribe he had taken hostage, arrived at Joara, a village at the base of the Blue Ridge about 12 miles northwest of today’s Morganton. De Soto’s band would be the first Europeans to cross the mountains.

Though it was spring, streams were still rimmed with ice, and patches of snow testified to recent blizzards. Much of future North America and northern Europe were gripped in the talons of the Little Ice Age. Climate change and resulting poverty, disease, and war drove the exploration of North America.

Around 1250, temperatures in the Northern Hemisphere on either side of the Atlantic began to fall. Seasons became capricious. Months of cold were so intense that London merchants held market fairs on the frozen Thames only to be followed by springs and summers of unpredictable drought or deluge.

Agriculture failed. Starvation, malnutrition, and disease spread across both sides of the Atlantic. Sweeping through Europe, the Black Death killed around 40 percent of the population. Desperation plagued monarchies. Much of their wealth depended on taxes paid in tithes of grain and livestock from starving peasants futilely working barren fields. The Hundred Years war erupted in 1337 between England and France, and Spain was drawn into the conflict. Bullion to pay armies was scarce; the few gold and silver mines on the continent were exhausted.

In search of new sources of wealth, Columbus’ voyages led the way to the Caribbean and Mesoamerica. Though only 14 years old, de Soto’s schooling in the violent arts of extorting and enslaving Native Americans began in 1514 with his arrival in Castilla del Oro, today’s Panama, as part of the largest expedition Spain had yet sent to the New World. For 22 years, de Soto pillaged Aztec and Incan cultures, earning a reputation for intense bravery and brutality while amassing a fortune of silver and gold. His partner, Ponce de Leon, named La Florida and claimed it for Spain in 1513.

De Soto returned to Spain in 1536. Though fabulously wealthy in his own right, de Soto defrauded de Leon of a major share of his wealth. The following year Charles V, King of Spain and Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire, granted de Soto the governorship of Cuba. In addition, he was awarded the right to explore, conquer, and administer all of La Florida as the North American continent was then known by the Spanish.

With his conquistadors, horses, pigs, and other provisions, de Soto landed on the southern shore of Tampa Bay in May, 1539. Immediately he encountered people of the Uzita and Mocoso tribes, members of the Safety Harbor Culture whose domain rimmed the bay and extended from Ft. Meyers north to Cedar Key.

When the conquistadors arrived, the Native Americans were friendly. But as de Soto began dragooning them to serve as porters and looting their temples, they fought his northward advance through mangrove swamp and palmetto scrub using arrows tipped with stone points or stingray barbs. At Napituca, thought to be near present-day Live Oak, prisoners captured by conquistadores revolted. Scores of Native Americans were killed at the loss of only a few Spaniards.

By winter, the conquistadors had battled their way up Florida into the country of the Apalachee, the tribe that would give our mountains their name. Settling into winter quarters at Anhayca in today’s Tallahassee, then a principal city of the Apalachee, de Soto pressed the citizens for information about lands further north.

It was here de Soto encountered a Native American boy who professed to trade with other tribes far to the northeast, near “another ocean.” He also claimed to know of mines of gold and silver in the mountains, and told of a female chief of the Cofitachequi, a Native American province near Camden, South Carolina, who collected taxes from tribespeople paid in precious metals.

Thus was cast the die that brought de Soto into the Blue Ridge. In March of 1540 the conquistadors proceeded northwest to the broad Flint River near Newton, Georgia. From there they followed foothills edging Georgia’s piedmont toward the land of the Cofitachequi.

On an island in the Ocmulgee, they surprised the citizens of the chiefdom of the Ichisi (a multi-town region governed by a chief). While enslaving many, de Soto’s company found turkey and venison slowly roasting over an open fire. De Soto’s chroniclers called it a barbacoa, the first known European reference to Southern barbeque.

As they entered the Savannah River valley, they passed through deserted town after town. Unable to rely on food collected from villages, starvation threatened. Desperate for supplies, De Soto dispatched his ablest lieutenants on the strongest horses to fan out ahead, searching for populated villages.

The horsemen returned with captives who told of villages in the land of the Cofitachequi, near today’s Camden. After two days of hard travel, they reached the banks of the Wateree River. Before long, a chieftainess appeared on the far bank. Seated on cushions in a dugout canoe, she was ferried across the river and greeted de Soto warmly, removing several strands of large freshwater pearls from her neck and placing them around his.

She ordered the conquistadors to be ferried across the river in canoes. She set aside half the village for their use and had supplies of venison, turkey, corn fritters, and salt delivered to them. She showed them what the messenger had claimed to be gold and silver but which turned out to be copper and mica.

De Soto and his men returned the hospitality of the chieftainess, whom they later dubbed “Lady of Cofitachequi” by looting strings of pearls from bodies in the tribe’s charnel house. In the process they found what appeared to be an emerald. It proved to be a green glass bead instead. They also discovered a number of rosaries and two iron hatchets evidently made in Castile.

These, they came to understand, were artifacts from the failed expedition of Lucas Vázquez de Ayllón. De Ayllón had landed with 500-600 settlers and about 100 enslaved Africans on Pawleys Island, South Carolina, after their flagship ran aground on August 9, 1526. Soils proved infertile and Native Americans had no materials worthy of trade. Reconnaissance parties were dispatched on horseback. A more favorable site was discovered 200 miles down the coast at Sapelo Sound, about 40 miles south of Savannah.

Soon after coming ashore there on September 29, 1526, houses and a church were built, and the ill-fated settlement was christened San Miguel de Gualdape. Ravaged by unexpectedly cold weather, lack of food, disease, and native defense, the colony faltered. Revolt by enslaved Africans, the first recorded in what would become the United States, sealed the settlement’s fate. Slaves escaped and went to live with nearby Native American tribes. Colonists fled to Hispaniola. Of the original settlers, only 150 returned alive.

Although the gold and silver de Soto hoped to find in Cofitachequi turned out to be copper and mica, the Lady of Cofitachequi confirmed stories of gold mined in the mountains. Holding her hostage as a guide, de Soto’s band resumed their northward quest on May 12. Two days later they entered the domain of another native people, the Chalaque, as spelled by de Soto’s chroniclers. The name would later be anglicized as Cherokee.

Little more than a week later they reached Joara, today’s Berry Site. The village, robust compared to many others they had passed through, lay at the junction of two major Native American trails into the Cherokee Nation. One led west from the Piedmont, crossing Swannanoa Gap into the French Broad watershed, and the other ran north into the Tennessee Valley.

Joara is located in the most bucolic of mountain valleys, a broad level floodplain at the junction of Upper and Irish Creeks. Just to the northeast lies the hamlet of Worry. As one enters the valley from the west on Henderson Mill Road, it’s easy to picture the valley as it may have been when de Soto and his retinue arrived.

Small garden plots checkered the valley. At the far end of the floodplain and surrounded by palisades, houses clustered around a low mound topped with a rectangular council house. Well aware of de Soto’s advance, most villagers likely huddled, waiting within the palisades.

Bone weary and hungry, conquistadors were relieved when the chief provided corn and little “dogs” to eat. Baltasar de Gallegos, who’d been dispatched with a troop of men some days earlier to search for provisions, arrived with more food and grain for horses. Items of copper seen in the village encouraged de Soto that gold would be found in the mountains.

On May 25, de Soto and his band left Joara following the course of Upper Creek from one tiny floodplain to another like stairsteps up the mountains. Reaching the crest of the Blue Ridge, they bivouacked in an intervale beneath Jonas Ridge. Likely they passed through the low boggy gap along NC Route 183 between Rt. 181 and the Blue Ridge Parkway, crossed Linville River, and entered the headwaters of the North Toe River near Three Mile.

Perhaps aware that the conquistadors were entering territory controlled by a rival chief, the Lady of Cofitachequi pleaded to be allowed to leave the group and go off into the woods to relieve herself. Accompanying her was one of her female slaves who carried a large pouch of unbored pearls. Soon out of sight, she and her slave fled across the mountain. As they made their way back to Cofitachequi, she was joined by others who had escaped from the expedition.

Unlike the relatively-gentle courses of rivers and streams the conquistadors had followed through the eastern foothills and valleys of the Blue Ridge, the rivers of their descent on the western flank flowed over rapids and twisting gorges clogged with boulders. Though June approached, weather remained bitterly cold. Much of the time they were forced to wade in water as deep as their calves wearing boots little sturdier than high-topped moccasins.

Progress was glacial. After passing present-day Spruce Pine, de Soto’s band camped where the confluence of the North Toe and Cane Rivers form the Nolichucky. The morning of May 30, they entered the final treacherous stretch of the Nolichucky, passing beneath the rock cliff called Devil’s Looking Glass before finally breaking free of the mountains at Guasili, better known today as the Plum Grove archaeological site near Embreeville.

One can imagine their relief. Ahead lay the Nolichucky valley. Foragers no doubt spread out as de Soto and his army followed the river downstream. In a day or so, they would pass the mouth of Big Limestone Creek, birthplace of Davy Crockett over two hundred years later. On Saturday morning, June 5, conquistadores reached Chiaha, a large town on Zimmerman’s Island in the French Broad River now flooded by Douglas Lake.

De Soto’s band would follow the French Broad to its confluence with the Holston at Knoxville forming the Tennessee River. His route down the Tennessee would take them to northwest Georgia, then deep into Alabama and northwestward through Mississippi. Nearly a year after crossing the Blue Ridge he would reach the banks of the Mississippi River on May 8, 1541, the first European documented to have done so.

After forays southwest attempting to reach Mexico, de Soto and his company would return to the banks of the Mississippi.

There he died of fever on May 21, 1542. The remnants of his band would again try and fail to find an overland route to Mexico. Once more they would return to the Mississippi, and in boats cobbled together they drifted toward the Gulf, following the coast before finally coming ashore at the Spanish settlement of Pánuco in mid-1543.

De Soto’s expedition found no gold or gems as King Charles V had hoped. It did, however, contribute substantially to European knowledge of the geography, climate, native people, plants, and animals of the Southeast. These accomplishments were achieved at great cost. De Soto’s penchant for violence, enslaving Native Americans, and plunder lit long-lasting resentment against European explorers and spread diseases which, along with those brought by other Europeans, killed an estimated 60 percent of Native Americans in the Southeast.

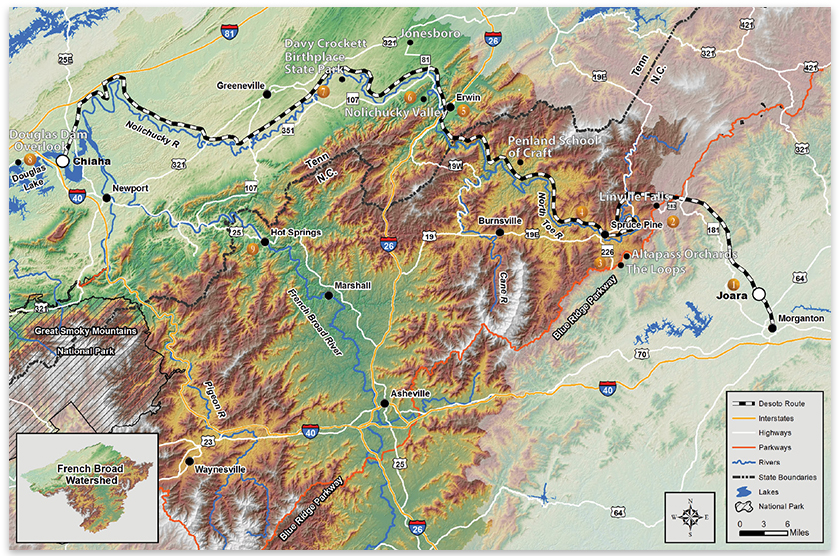

Desoto's Mountain Path - Follow the historic Blue Ridge route

1. Pick up NC Rt. 181 just north of Morganton. Head north toward Blue Ridge Parkway. Turn right onto Henderson Mill Road. Cross the broad valley through nurseries and imagine native farm plots with the village of Joara and mound at the valley’s far end by Upper Creek. exploringjoara.org

2. At Jonas Ridge, turn left on NC Rt. 183 and make the next right onto Donald Barrier St. You’ll cross boggy Camp Creek which conquistadors waded and then turn left on the Blue Ridge Parkway. Follow the parkway past the Linville Falls exit, Altapass Orchards and The Loops railroad overlook. About 200 immigrants died cutting 18 tunnels on the 32-mile route started in 1886 and finished in 1909. altapassorchard.org, hmdb.org

3. Leave the parkway at the exit for NC Rt. 226 to Spruce Pine. Across the way, visit the North Carolina Minerals Museum for a fascinating display of mining and gemstones in the Blue Ridge. nps.gov

4. Follow NC Rt. 226 through Spruce Pine to Penland Road, turn left and at the sculpture sign, make the sharp right leading to Penland School of Craft. Return to Penland Road, turn right and follow it through the hamlet of Penland founded in 1850 by Robert Penland. Its General Store and Post Office, one of the longest to be continually open in the Southern Appalachians, is on the National Register of Historic Places. penland.org

5. Continue to US 19E and follow it through Burnsville. About five miles beyond turn right onto US 19W. Take it to I-26 and Erwin, the railroad town where Mary, a circus elephant was hanged in 1916 for killing its handler who’d dared shock it with a cattle prod.

6. From Erwin follow Tenn. Rt 107 toward Jonesboro through Embreeville, Tennessee, where de Soto’s troops broke free at last of the Blue Ridge. Imagine the conquistador’s delight to be marching down the Nolichucky Valley instead of wading frigid streams. Rt. 107 makes a hard left at Crossroads Store as Rt. 81 continues to Jonesboro.

7. About 14 miles further turn right on Rt. 351, take it to Limestone and follow signs to Davy Crockett Birthplace State Park. The frontiersman and Congressman was surely born in Tennessee, but not on a mountain top as the song goes.

8. Pick up US 321 at Limestone and follow it south to Newport. Take I-40 west toward Knoxville. After I-40 junctions with I-81, continue on I-40 to the Deep Springs Road exit. Turn left and follow it to Douglas Dam Road. A right turn will take you to the Douglas Dam overlook. Look up the lake, inundated before the ridge in the distance is Zimmerman’s Island, location of the native town of Chiaha where conquistadors rested for three weeks after crossing the Blue Ridge.

9. From Douglas Dam, backtrack to I-40 and follow it east to Newport. Pick-up US Rt. 25 toward Hot Springs. Hot Springs may have been a tourist destination for at least 5000 years. Pictographs on nearby Paint Rock, according to archaeologists, were painted in blue and orange by people of the Archaic era to tell others of where they might relieve their aches in warm springs up the river In the village, something of a hikers’ and bikers’ mecca today, British musicologists Cecil Sharp and Maude Karpeles collected many of English ballands featured in today’s bluegrass music. hotspringsnc.org