Renaissance Summers

Renaissance Summers: At Camp Catawba, boys found an artistic escape from a world in turmoil

Of the myriad camps that have hosted unforgettable summers in Western North Carolina, it’s safe to say that none were quite like Camp Catawba. Situated on 20 acres adjoining what’s now Moses H. Cone Memorial Park near Blowing Rock, the camp began as a haven from the perils of the world and evolved into a vibrant cultural incubator. A boys’ camp in the mountain South, it was run by two women who hailed from far away. As unlikely as it seemed, Catawba’s mix of high art and traditional summer camp fare found the perfect home in this lofty, remote patch of rural Watauga County.

Place of Wonders

Another singular aspect of Catawba is that its history is extensively detailed, thanks to a 1973 book by a former camper and counselor, the late Charles Miller, who spent 12 summers at the camp. Titled A Catawba Assembly, it chronicled the full life of the camp and shared memories of more than 100 people who attended or worked there. Catawba was “more than a camp,” Miller asserted. “Many campers and staff became deeply attached to the camp’s concept of community and to the cultural and spiritual values which the camp represented.”

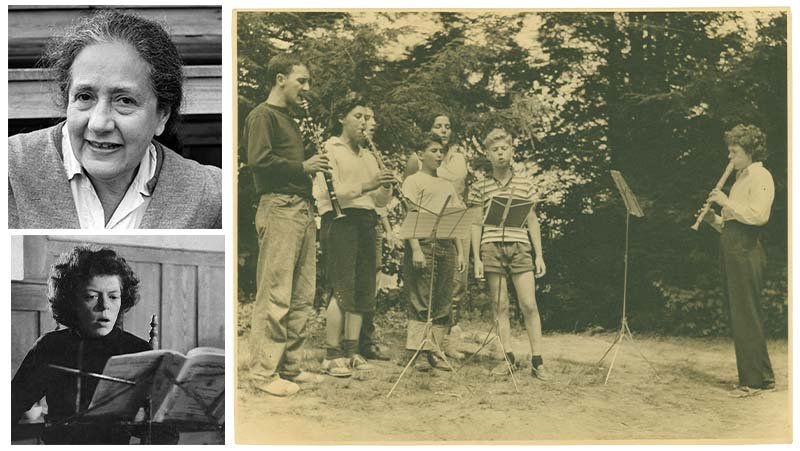

Those values were embodied by the camp’s founder and director, Vera Lachmann. She was born in Berlin in 1904, to a German-Jewish family with aristocratic roots. Lachmann’s upbringing was immersed in classical education, and she gravitated toward Greek and Icelandic poetry while training to become an educator. By the time she began teaching in the early 1930s, the timing was both terrible and fortuitous: as the Nazis increasingly barred Jews from public education, Lachmann founded her own private school to help make up the deficit in her community. She weathered the anti-Semitic storm until later than many of her friends and family members did, fleeing Germany only on the cusp of war in late 1939.

Lachmann emigrated to the US, finding part-time employment teaching German, poetry, literature, and other subjects at colleges and camps. But she longed to again run her own center of learning, one that could cater to children who, like her, had fled fascism and its poisoning of the arts. With an assist from friends in North Carolina, she found and purchased the land for Camp Catawba from a local lawyer—for $3,500, which Lachmann paid in $500 annual installments.

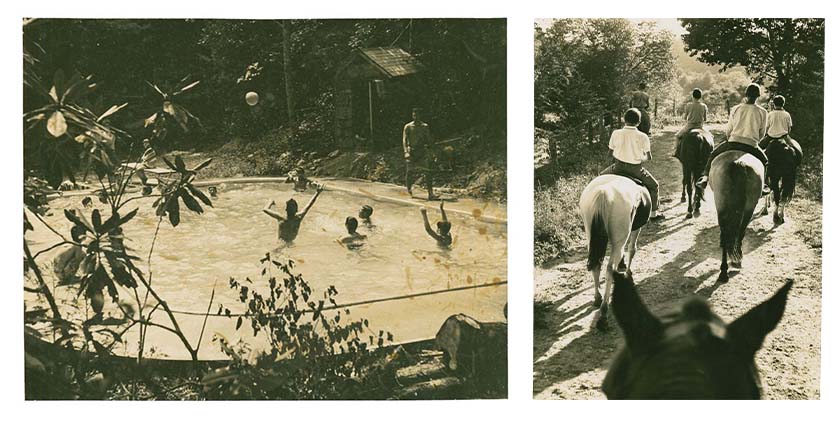

The land—the site of a former girls’ camp, with three abandoned buildings and little else—would make for spartan accommodations at first, but Lachmann immediately sensed it was “a place of wonders,” as she put it. In the summer of 1944, she hosted her first crew of campers, six in all, with the numbers increasing each year. Many of the early campers had fled the war as well, and many were also Jewish. Almost all were, like Lachmann, starting new lives in and around New York City, so that first season in the North Carolina mountains was yet another alien experience. But Lachmann had a secret weapon to calm their souls: music.

“Music was as much a part of Camp Catawba as the Blue Ridge Mountains,” Miller would remember. And while several staffers helped sound the tune, the camp’s music director, Tui St. George Tucker, was the conductor. A diminutive woman with fiery red hair and an intense demeanor, Tucker was a composer who specialized in microtonal tunings and avant-garde stylings, along with more classical approaches. Her instrument of choice was the recorder. A California native, she’d met Lachmann in New York, where the two women became life-long companions.

With Lachmann heading classes in theater and literature and Tucker leading ensembles and choruses, Camp Catawba became a summer hotbed of practice and performances. Former camper Dean Pearlman remembered the “ever-present emphasis on creativity, plays, composing, music, singing, drawing, arts and crafts.” In 1954, a camp newsletter could rightfully boast that “no other camp … wakes up to Bach cantatas, oratorios, passions, masses, fugues, and unaccompanied cello suites.”

After a while, the camp’s reputation spread, both locally and back up north. Catawba came to host annual concerts and plays for the Blowing Rock community, and groups of campers even performed together on notable stages in New York.

Over the years, Catawba’s base of recently refugeed children expanded to include campers of many backgrounds, and in 1964, the camp integrated. “We are trying the unlikely,” Lachmann wrote in one letter to parents. “We should like to have the boys learn to live in a group, respecting other individuals. To be happy without tramping on anybody else’s rights. To enjoy the beautiful instead of the cute. To have the courage, both physically and morally, and the fun of their age, instead of imitating the boring amusements of helpless grownups.”

Plenty of Play

Camp Catawba wasn’t all high-minded idealism and disciplined instruction. In fact, what many campers remembered most were the more typical camp activities, which were bountiful. Archery classes, treasure hunts, swimming holes, horseback riding, campfires, field trips—Catawba had it all. And its outdoor offerings were particularly outstanding, given the setting: for their regular hiking grounds, the campers reviled in the nearby Cone Estate and Grandfather Mountain, among other area standouts.

Nor was Catawba a utopia without significant challenges. The camp faced near constant struggles with infrastructure, finances, and, to some degree, general planning. “Vera was always director, but did not always direct,” Miller remembered, while stressing his fondness for her. “She left substantial portions of her ill-defined job to others, or sometimes to no one.” But the boys didn’t seem to mind Lachmann’s laissez-faire approach, and in fact many of them came to embrace Catawba’s unique, if somewhat disorganized, way of doing things.

And fortunately for Catawba, there were year-round neighbors to assist with the camp’s summer operations, most notably a local farming couple, Ira and Sally Bolick. They were much older than the campers, but were always welcoming and quick to help by doing repairs, lending tools, and sharing their mountain food and folkways. The Bolicks, many campers recalled, imparted a whole other kind of educational and cultural experience.

The days of rigorous play and learning always ended the same way: with Lachmann sending the weary boys off to slumber with ancient and dramatic bedtime stories. She remained, throughout Catawba’s 27 summers, a font of wisdom, curiosity, and compassion.

Former camper Mark Wolff remembered Lachmann as someone “who used to get up early to give Greek lessons to the counselors before breakfast, who sat in a circle with us after breakfast every morning and always listened when we spoke. This lady went hiking with us and directed us in a play. And every night she told us a part of the Iliad or the Odyssey. And finally when we were in bed, she came to say goodnight to each of us, and to speak to us if we had some trouble during the day.”

Dear Piece of Earth

By the time the camp closed after the summer of 1970, when Lachmann retired at 65, Catawba had shaped the lives of more than 400 boys. Many of them, sparked by their renaissance summers at the camp, went on to become noted artists, musicians, teachers, and writers. Lachmann and Tucker continued to summer at the site until Lachmann passed away in 1985. Tucker then moved there full-time, composing music until her death in 2004. In accordance with Lachmann’s wishes, the property was sold to the Blue Ridge Parkway, which owns it today.

Charles Miller, Catawba’s historian, continued to document and promote the legacy of the camp until he passed away in 2019. Many of the archival pictures, recordings, programs, and papers he and others gathered are now in the good hands of Belk Library’s Special Collections at Appalachian State University.

The artifacts are reminders that, in retrospect, Lachmann’s dream—although rerouted by the trauma of war and dislocation—was more than realized at Camp Catawba. In fact, it multiplied through the lives and careers of her campers, two generations of which shared her reverence for Catawba, which she recorded in verse:

You dear piece of earth, wafted over by butterflies, where the hydrangea stands with the clusters—how I shall miss you.

Will you wait for me through the year, greeting me first with strawberry drops in grass hair and then with the blackberries’ shiny miters?

Oh, guard what is … and what was.