Red Clay and Pretty Talk

Red Clay and Pretty Talk:

There’s nothing worse than being trapped in a car with a writer from Alabama.

They’re either complaining as to the length of the trip or taking a nervous pill if the speedometer registers above the posted limit. What’s most grating is when they get to waxing rhapsodic about the literary history of their state as if the names Thomas or Reynolds or O. Henry never graced a book cover or crossed their narrow minds. Makes it damn hard to be a Christian.

A few years back, I was driving on Scenic 98, along Mobile Bay, past waterfront houses and grand hotels, with an Alabama writer boy riding shotgun. He took his eyes from the brackish water and postcard view of sailboats and seagulls, turned to me and said, “You’ll move here someday, won’t you, to be near other writers?”

I thought of red clay.

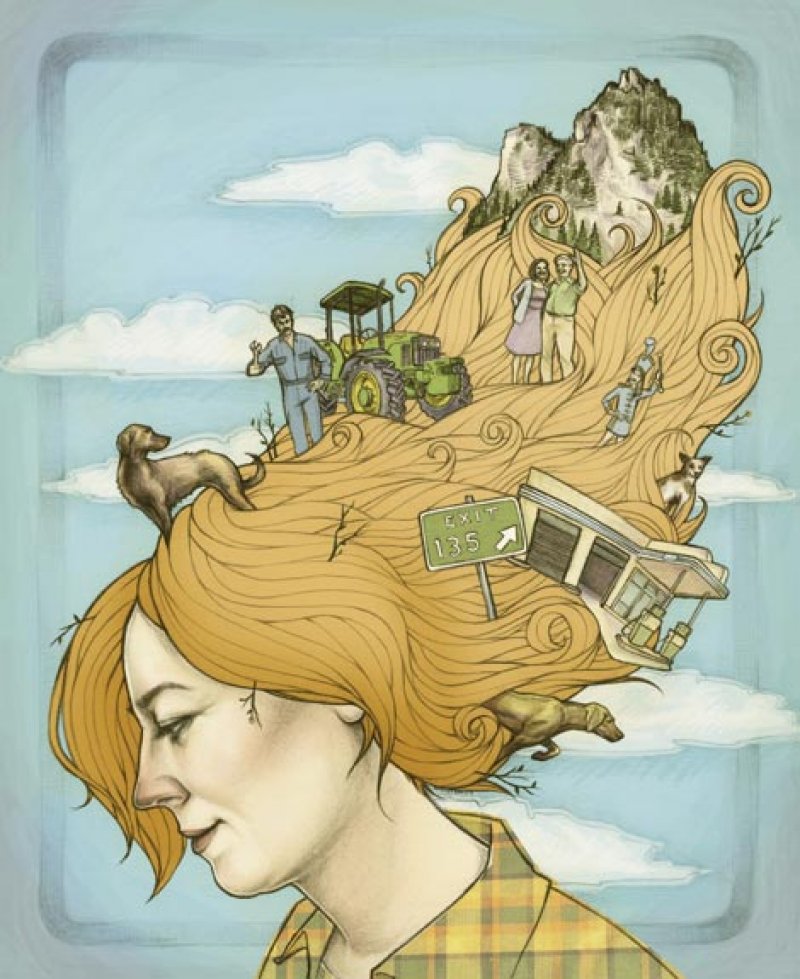

I don’t reckon anybody ever drove through my Carolina town for the view. Unless you’re coming to see your momma, the only reason to take exit 135 off Interstate 40 is to fill up the tank or empty your own. That was pretty much the marketing strategy of my buddy, Jeff, who opened a restaurant out at the highway and named it Boxcar, complete with a ticket window where the hostess takes your name and the number in your party and a dinner entrée called Trolley Tips. They even nailed a fake run of railroad track to the wall behind the salad bar. Weekend tourists don’t come to peep at the leaves, nor do we have any slopes to ski down. Nobody’s making fudge or boiling peanuts and hawking them to the patrons coming to town for the art festival.

We don’t have an art festival.

We have three stoplights, two more than we really need, a place to order flowers for funerals and prom night, and an impressive pack of stray dogs. They’ve defied the efforts of county animal control, breezing past traps baited with steak, and produced at least three litters of puppies, which all found homes despite the gypsy souls of their parentage. We gave up on catching them a long time ago. I was sitting in the police station, by choice not incarceration, when Pam, who answers the phone and decides who gets buzzed in, looked out the window and said, “There go our little bandits,” as they trotted on down the sidewalk on Main Street without care or concern, other than getting to the dumpster behind the Claremont Cafe. We have two banks where the tellers know our names and account numbers by their blessed little hearts. We have a volunteer fire department and an active Lions Club that ran the Jaycees out of town. We have Eddie, the mechanic, who pointed a wrench at me one day and said, “Listen, here. Don’t go lettin’ any of them stupid boyfriends work on this John Deere ever again. It’s mine, you hear? I ain’t fixin’ their mistakes, no more.”

I haven’t cheated on Eddie since.

Town drunks are allowed to walk the streets and sleep where they wish as long as they clean up their empties. Not doing so is just sorry and while sober is not required, respect for the town is. In church, babies are passed and prayers are said for sick folks even if we really don’t like them all that much. I am welcome at each of the five churches in town, expected at none. The men who sit at the back table of the Claremont Cafe will argue for days over the best route to take when driving anywhere outside the state, often over the difference of less than 20 minutes. Everybody comes to watch the Christmas parade, all three blocks of it. We can see the mountains from our kitchen windows, but like many beautiful things, they are out of our reach.

From time to time, people will ask me why I came to Claremont. My answer is that though I came for the wrong reasons, I stayed for the right ones. I am here for the family that circles around me in good times and complete devastation. I am here for the familiarity of finding tulip bulbs in a Dollar General sack outside my back door, dug up and left for me by my neighbor, the best gardener in town; the smell of the heart-stopping grease when the door to the Cafe eases open; the annual telling of the Christmas when the Savior was stolen from a manger scene outside one of our churches, only to be recovered when the waitress at the Waffle House in Hickory called the sheriff and said, “There’s a drunk standing in the parking lot holding baby Jesus and crying.”

Bless his heart.

I am here for the rhythm, the cadence of the language of rural Carolina. It plays like music in my head. Tim Yount is wicked smart with a lightning quick wit, though not much for tending to his own yard work. He reads three newspapers every morning, can quote Updike like he wrote it, and spent last election day working the polls to see that a good judge stayed on the bench. But, on a particularly bad day for both of us, though for different reasons, Tim said to me, “Sugar, we might should pitch a good drunk.”

All men should talk pretty that-a-way.

I don’t complain about Proctor & Gamble’s failure to invent laundry soap that will remove the red clay from my clothing. I wear it, glad it won’t come out. There’s no separation in my mind between this land and these people—these people who punch clocks and line up at sewing machines to stitch together sofa cushions for other families to sit on; this place where you recognize a furniture builder by the cracks in his front teeth from holding tacks in his mouth trying to go faster—making his quota, but missing his aim when bringing the magnetic hammer to his lips. Jerry Hoke’s birdhouses, Miss Peggy’s pound cake, the quilts of the Ladies of St. Mark’s Lutheran Church, Gary Sigmon’s ’66 GTO that outran the law and brought him on home, time and again—each one a good story that should be told, and deserves to be remembered. A writer doesn’t need to be with other writers. We need to be where there are stories to tell.

Driving along that bayside highway, I looked at the boardwalk, at women in oversize sunglasses, wearing capri pants with sweaters tied around their necks. Remembering the red stains on the frayed hem of my jeans, I said, “No, I’m a foothills girl. I’ll stay in Carolina with my people.”

Shari Smith is currently working on a nonfiction book about her adopted hometown of Claremont.