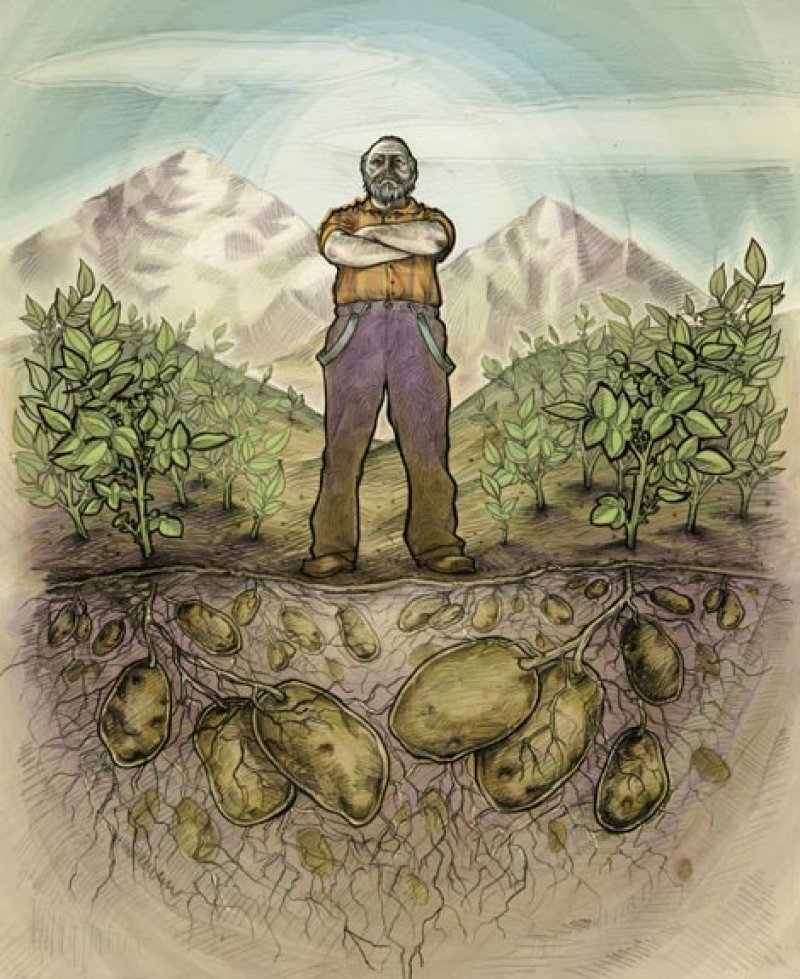

The Potato Patch

The Potato Patch:

Amazing how a twenty- by fifty-foot strip of hard clay soil, cut off by a bold creek on one end and a dead-end road on the other, could mean so much.

I live on a small farm that’s steep as a mule’s face and configured like a derby hat that’s had the back half cut away. The only available flat land lies like the hat’s narrow brim, curving along the contour of the aforementioned bold creek that divides my property from my neighbor’s. Our house clings to the looming wooded hillside like a buckle on the hatband. When my wife and I bought our place in Yancey County back in the ’80s, the only existing rights-of-way were a walk bridge thirty feet long and a bushel-basket wide, and an oak-planked drive bridge that lay at the bottom of an abrupt hill some three hundred feet from the house.

My neighbor had this nice level strip of land that led to what could be a natural driveway of bottomland along our side of the creek and right up to our house. The strip had potatoes planted, but nothing else. Tangles of catbrier and blackberry cane coiled along the sides. Bee balm and stinging nettle settled thickly near the border with the creek.

The potato patch appeared to profit him little. But it promised us a safer, more efficient way to bring firewood closer to the home that would burn it for winter warmth.

Everybody called my neighbor “Sonny,” even though he was in his 60s by then. A tall man, all nose, sinews, and cigarettes, Sonny didn’t suffer fools or beggars. Or flatlanders who might turn out to be both.

We waited two years before asking.

“Sonny, do you think you might want to sell that little potato patch to us so we can throw a bridge across it?”

His craggy face darkened and his mouth folded into layers of resistance.

“Naw, I don’t think I would.”

We let the matter be.

A few years later, the matter resurrected itself. I had rebuilt the walk bridge, but only wide enough for three men and a boy to carry a woodstove across it, which happened twice. I had almost driven my truck off the icy plank bridge several winters in a row, too. I’ll not detail our yearly ordeal of using mules to drag down—and humans to hand carry—firewood logs to the house, except to point out that “death by mule” is excluded by many a homeowner’s insurance policy.

It was too much aggravation. It would be simpler to buy split firewood and truck it over that flat potato patch and haul the wood right up to the house.

I dearly desired that potato patch.

One summer, I saw Sonny sneaking toward the roadside corner of the potato patch. He had hornet spray in one hand, a small gas can in the other. I noticed raised red blotches on his leathery arms and one centered on his forehead.

“’Lo, there, Sonny. What are you into?”

“’Lo, Brian. Got a big yellerjackets’ nest there. Them sorry boogers deviled me for the last time. I got somethin’ right here they’ll remember me by!”

I watched him spray the hole, splash it with gas, then toss his cigarette on it. There was a huff of ignition, a ball of flame that rolled away and blended with the summer’s heat, followed by a few stray wisps of smoke that arced toward the ground, wiggled a bit, then curled up dead.

I shared his satisfaction. Then I asked him about the potato patch.

“You ever sell your potatoes?”

“Naw. Wouldn’t make nothin’ if I did. The big stores sell them ones from Ida-ho so cheap it’s un-real.”

“You just grow them for yourself?”

“Yep. A man won’t starve so long as he’s got taters dug in somewheres.”

“Well, if a man was to pay you three times the value of all the potatoes you could ever dig up in a year—just so he could get at his firewood—would you take it?”

He frowned and spat.

“Loggin’ would compact the soil. Hit would be ruined.”

I fought back.

“But no more than your tractor’s wheels do every year?”

“I think it would. Nosir, I wouldn’t allow it.”

The score: Sonny 2, Me 0.

Years later, Sonny trapped a ’coon down there. He was 80 by then. He was scared to dispose of it because he was sure it was rabid, which he pronounced “ray-bid.” I got rid of it for him. He was grateful. He got talkative and lapsed into telling hunting tales.

I sensed another opportunity. It was now or never.

In my dreams, I would gamble everything, promise anything. I’d smother him with truckloads of organic potatoes, pave the patch’s borders with hand-painted tiles bearing the likenesses of Sonny and Dale Earnhardt, enrich the soil with the finest manure from champion show cattle.

But face to face with the man, I could only offer this.

“Sonny, I’d like to buy that potato patch from you. Name your cash price, and I’ll gladly pay it.”

He was silent for too long. His face gave away nothing.

When he finally spoke, he looked at his feet as it came out softly, steadily—history aimed at the ground.

“Papaw John grew his taters here. Taters had always been grown here. ’Backer and corn everywhere else, but taters from right here.”

And then his final word on the matter.

“You just want this piece of land. You don’t need it. But I do. And I’ll not sell it for love nor money.”

He’d made his point. I won’t ask him again.

You got to keep straight what you want from what you need.

Brian Lee Knopp is a former private investigator, criminal defense investigator, and professional sheep shearer. He is the author of the bestselling memoir Mayhem in Mayberry: Misadventures of a P.I. in Southern Appalachia.