Out of the Ashes

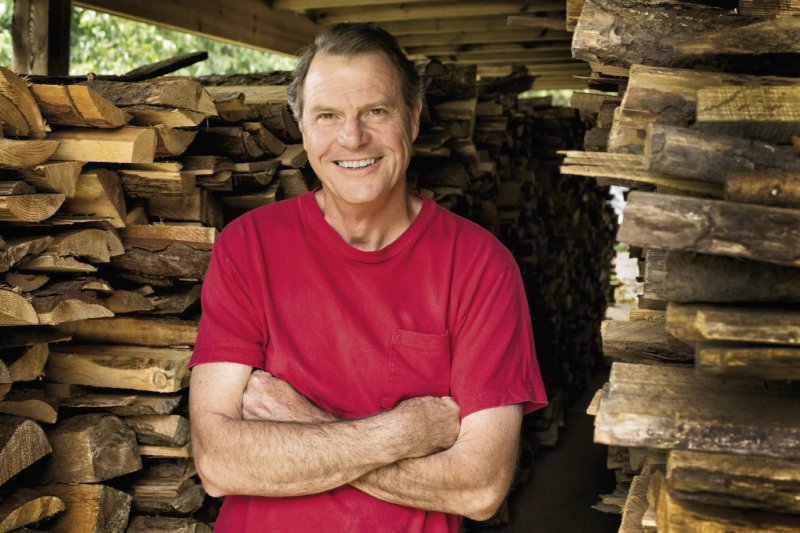

Out of the Ashes: Kim Ellington keeps the Catawba Valley pottery tradition alive

As the story goes, the formula for the alkaline glaze used in Catawba Valley pottery traveled from China to Charleston via 18th-century French Jesuit priests, who passed it on to Charlestonian potter Abner Landrum. He, in turn, brought the glaze to Edgefield, South Carolina, in the early 1800s, and it made its way up to the Catawba Valley. Fast-forward to the 1980s, when Vale potter Kim Ellington learned it from Burlon Craig, whom Ellington calls “the last person standing” in this “pure folk tradition.” In that way, Ellington’s own work can trace a direct lineage back to the early days of the North Carolina frontier.

After studying at what is now Haywood Community College’s Program in Professional Craft, in 1982 Ellington opened a pottery shop in Hickory, using manufactured clays and forms he’d learned in school. People began bringing in pieces of bulbous, ash-glazed pottery and asking if he could identify them. “I’d never seen anything like it,” he recalls.

Tracing it back to its point of origin, he found a place called Cat Square and a pottery legend named Burlon Craig. “He blew my boat out of the water,” says Ellington. “I chucked seven years of experience and found a new way through the old way.” Through Craig, Ellington learned to build a traditional kiln called a groundhog kiln. And Craig gave him the formula for the wood-ash glaze not in writing, but by passing it from mouth to ear, the way it had been done for more than 250 years. “When I think about it, I realize that I was part of something very special,” he says.

The Catawba Valley was settled by Germans who were making their way down the Great Wagon Road from Pennsylvania, says Ellington. They brought their Rhineland pottery traditions with them: big whiskey and molasses jugs, milk crocks, and kraut jars for pickling. The Chinese alkaline glaze they adopted was simple, made from seven parts wood ash, five parts ground glass, and two parts clay. The forms and the glaze are part of what makes Catawba Valley pottery distinct, but it’s the local clay that seals the deal, says Ellington. “It’s incredible stuff. You can make large forms from it but it’s very light.”

Catawba pottery is experiencing a revival now, says Ellington, who is passing on his knowledge to students at Catawba Valley Community College. Even though his forbearers were mostly farmers who made pots part-time for practical purposes, “they took a lot of personal pride in their skills and in the process,” he says. “It’s a high standard to live up to, and its part of what keeps me interested. I’m just another word in the sentence of how this tradition lives on in this community.”