Moving in Harmony

Moving in Harmony: The new Safe Passage campaign envisions wildlife crossings along human-heavy routes

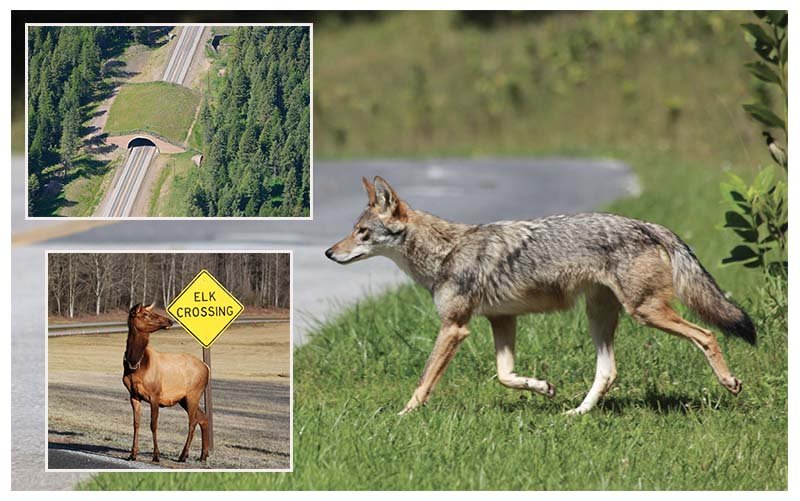

Each time animals like this coyote in Shenandoah National Park decide to cross a road they risk their lives; (inset top left) A wildlife overpass on the Trans-Canada highway in Banff National Park. Such structures are more expensive than other options, but they offer superior connectivity for wildlife that will not cross under roads; (inset bottom left) A female elk pauses beside a road sign near Cherokee.

Western North Carolina is beloved—and coveted by those who don’t live here—for its lush, scenic, and diverse natural wonders. One need only go for a drive along any picturesque area highway to revel in the multicolored mountain views and misty vegetated landscapes unique to this region. If you find yourself out and about at dawn or dusk, you might even glimpse an American black bear, elusive fox, or shy bobcat crossing your path.

Yet all too often, the spontaneous drive to take in WNC’s beauty also takes us past dead bodies—the mangled, bloodied, lifeless forms of deer, coyote, and even bear along with many other species that can be seen along local roadways. What’s more, we take our lives into our own hands on these scenic drives. In North Carolina alone, between 2017 and 2019, there were 56,868 wildlife-vehicle collisions, more than 2,800 human injuries, and five human fatalities—and all this cost $156.9 million in property damage, according to the NC Department of Transportation.

A new group of collaborators believes it’s time for the Southern Appalachians to start making changes to regional roads so that animals and humans can coexist in harmony. Safe Passage: The I-40 Pigeon River Gorge Wildlife Crossing Project is a collection of nearly 20 federal, state, tribal, and nongovernmental organizations working to make a perilous stretch of highway near the Smokies’ boundary more permeable for wildlife and safer for drivers.

(Clockwise from top) This aerial view of Interstate 40 shows how the highway intersects vast tracts of national parkland that are huge animal habitats; A fawn refreshes with water near a culvert—a structure that can also help critters cross under roads; Kim Delozier (left), then of the Rocky Mountain Elk Foundation, and Jeff Hunter of the National Parks Conservation Association confer during the early planning stage of Safe Passage.

Coming soon to WNC

The approach has a solid track record: France was the first to do it, and it’s since been done successfully in the Netherlands, Switzerland, and Germany. They’ve done it along the Trans-Canada Highway in Banff, Alberta, and in various connected lands throughout Montana, Massachusetts, Florida, and Southern California. They’re doing it in White River National Forest near Glenwood Springs, Colorado, and in the Snoqualmie Pass area of Interstate 90, Washington state’s transportation corridor over the Cascade Mountains. Large overpasses positioned to accommodate migratory patterns in Utah and Texas have even gone viral on social media of late.

Safe Passage, for its part, is particularly focused on 20 miles of highway in WNC and eight miles in East Tennessee in the Pigeon River Gorge, a wild, rugged landscape almost identical to that of the nearby Great Smoky Mountains National Park. For more than two years, researchers here have been studying the movements of megafauna—black bear, elk, and the ubiquitous white-tailed deer—as well as many smaller species. They’ve been seeking the answers to questions like: “Where are animals successfully crossing the roadway?” “What species are crossing via existing options like culverts designed to move water?” and “At what hot spots are the most animals dying?”

“Interstate 40 cuts Great Smoky Mountains National Park off from large public lands—Cherokee and Pisgah National Forests—to the northeast,” notes Christine Laporte, the eastern program director at Wildlands Network, a nonprofit active throughout North America. “Projected movements of climate-driven species suggest there will eventually be a high concentration of animals migrating northward into the Appalachians from further south. Securing habitat and safe passage across roadways is imperative here in the Southern Appalachian Mountains and throughout the Eastern Wildway”—an extensive wildlife corridor linking eastern Canada to the Gulf of Mexico.

The organization works to restore, reconnect, and re-establish wildlife corridors that have been fragmented throughout the eastern United States. Based in Asheville, Laporte helps to steer the Safe Passage Fund Coalition, comprised of Wildlands Network, The Conservation Fund, Defenders of Wildlife, Great Smoky Mountains Association, National Parks Conservation Association, and North Carolina Wildlife Federation. Their new website, SmokiesSafePassage.org, seeks public donations for a fund that will help improve I-40 over the next few years, making travel safer for both wildlife and humans in the Pigeon River Gorge.

“Our highway infrastructure was built during the 1960s without any thought for wildlife or their movement patterns,” says Tim Gestwicki, Charlotte-based CEO of the North Carolina Wildlife Federation. “Solving this problem will require long-term strategizing and resources from departments of transportation, federal and state governments, and society at large. We are gearing up for a convergence of all of these in the near future, and the Safe Passage fund provides a way for the public to pitch in right now.”

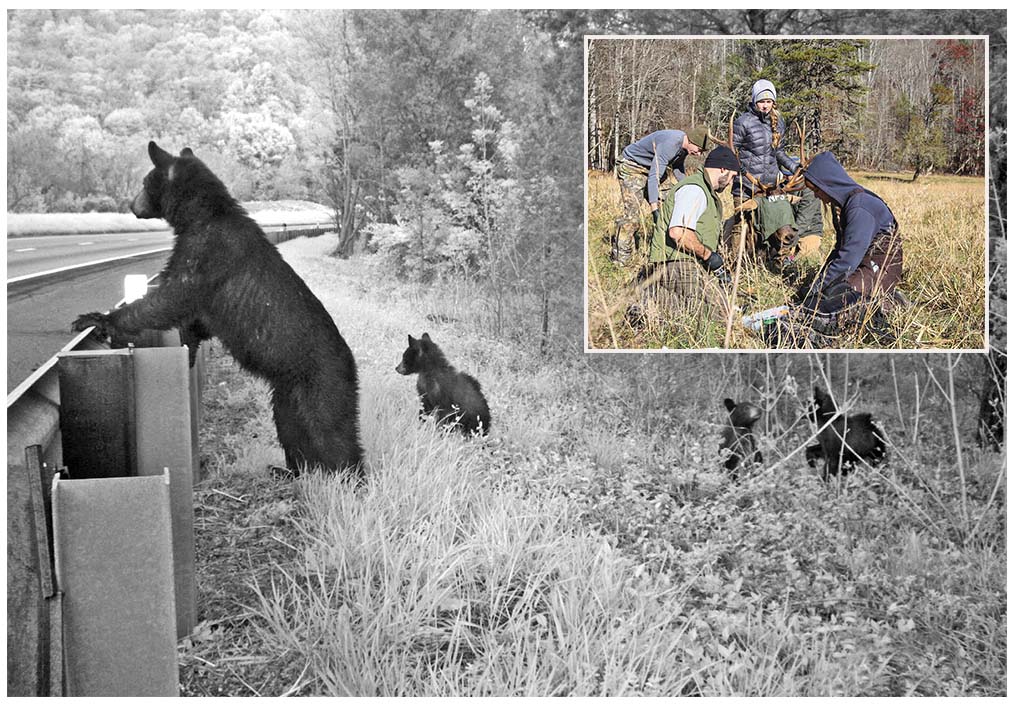

Symbolic of the risk–reward situation that animals face when they search for food, security, dispersal, or breeding, a female bear looks for the best opportunity to cross with her cubs at the guardrail on I-64 in Virginia near the top of Afton Mountain, where the Shenandoah National Park and the Blue Ridge Parkway meet; (Inset) Staff from Great Smoky Mountains National Park, National Parks Conservation Association, and Wildlands Network collaborate to place a tracking collar on an elk.

Tracking Wildlife Movement

With North Carolina currently the eighth fastest-growing state in the union and Great Smoky Mountains National Park the most visited park in the US, the Safe Passage project recognizes an urgency to get wildlife crossings underway. That pressure is increased by growing populations of megafauna.

There were probably less than 500 black bears in the Smokies when I-40 was constructed, and now the population is estimated at around 1,900. A recent study determined that more than 90 percent of male bears and 50 percent of females regularly travel out of Great Smoky Mountains National Park to access other habitats. This inevitably means they have to cross regional highways as well as secondary roads.

Reintroduced in 2001, the park’s herd of elk—one of the largest remaining terrestrial animals in North America—is also growing and starting to expand. Young males are dispersing to look for new territory, which means moving out of the park, and some are now taking up residence on either side of I-40.

North Carolina Wildlife Federation partnered with Wildlands Network and National Parks Conservation Association in the research funded by Volgenau Foundation. Data from GPS collars to track elk movements and 120 wildlife camera traps are allowing scientists to make recommendations for the best ways to mitigate I-40 for wildlife as state transportation agencies improve several bridges in the gorge over the next five years.

“Regionally—and nationally—this area is widely considered to be of high conservation value because it is comprised of key habitat corridors that are critical for the long-term flow of plants and animals,” says Steve Goodman, a Volgenau-funded wildlife scientist conducting research in the gorge with National Parks Conservation Association. “In addition to reducing wildlife road mortality and improving public safety, our work will help ensure ecosystem resiliency and improve wildlife connectivity across the larger fragmented landscape.”

Frances Figart is the editor of Smokies Life magazine and creative services director for the Great Smoky Mountains Association. Learn more about the initiative at SmokiesSafePassage.org.

Follow the Journey

A new book by Frances Figart, A Search for a Safe Passage, parallels the I-40 Pigeon River Gorge Wildlife Crossing Project by telling the adventurous fictional saga of some of the region’s signature animals and how they must grapple with migrating among their encroaching human neighbors. Targeted for a readership ages seven to 13, the story is supplemented with maps, profiles of area megafauna, and a helpful introduction to the mounting movement behind wildlife crossings. Available from booksellers and at smokiesinformation.org.