From the Mountains to the Sea

From the Mountains to the Sea: A visionary effort to create a statewide trail has been 40 years in the making. With the path now finished in Western North Carolina and a groundswell of support rising in the East, the completion of North Carolina’s most monumental natural treasure is on the horizon.

One of the many awe-inspiring scenes along the Mountains-to-Sea Trail is the view from Shortoff Mountain, located in Segment 4 of the MST, on the Southern rim of Linville Gorge, looking toward Lake James.

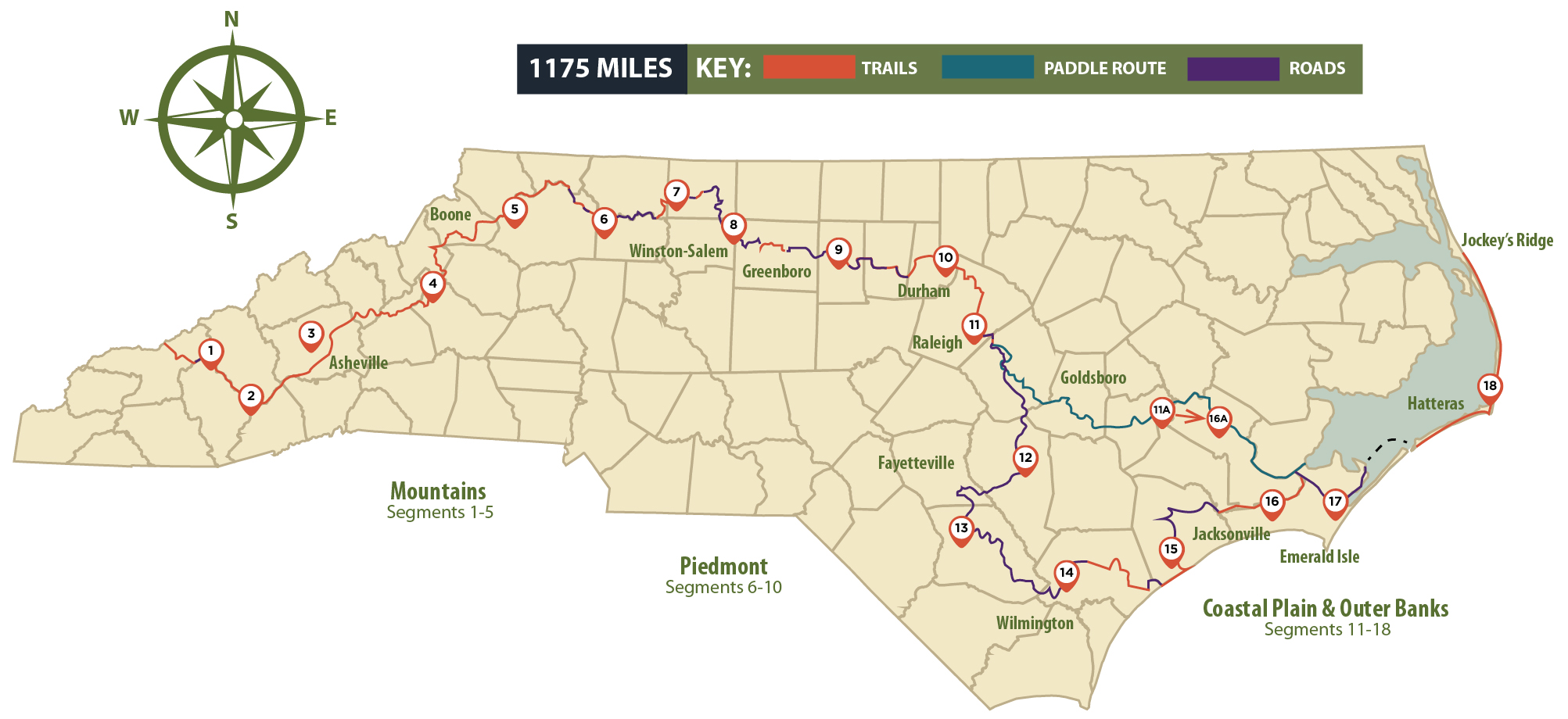

In Western North Carolina, trails lead just about everywhere, with some offering grand distances. The white rectangle blazes of the popular Appalachian Trail can take you over 2,000 miles. Next stop, Maine or Georgia. But there’s another long-distance hike accessible in WNC that’s set to become a North Carolina treasure. The Mountains-to-Sea Trail (MST) stretches from Clingmans Dome in the Smokies to Jockey’s Ridge on the Outer Banks, passing Blue Ridge vistas, idyllic farms, and bygone textile villages, through forests and coastal swamps, past lighthouses and sand dunes, to reach the Atlantic.

Unlike the AT, which traverses mostly wilderness, the MST follows a mix of forested pathways and temporary routes along rural country roads, offers two ferry crossings, and has one section in the east where hikers can opt between paddling a portion of waterway versus walking a more southerly route. While the ultimate goal is to create a continuous off-road trail, all 1,175 miles can be hiked right now, and a growing number of thru-hikers are following the MST’s white circle markers all the way. It’s taken 40 years to come this far and will take even longer to reach the goal, but here in the mountains, as of last fall, the entire 350 miles from Clingmans Dome to Stone Mountain State Park was deemed finished.

The milestone, marked during a dedication ceremony that gathered local, state, and federal officials in Great Smoky Mountains National Park, is part of a groundswell of public support that’s been building over the past 12 years. Steady funding that’s making the trail a reality comes primarily from individuals and businesses, while federal land agencies and state and local governments have assisted with land acquisition and easements for the trail to be built on. Civic organizations and trail clubs have aided in trail construction and maintenance. All this enthusiasm is flowing across the state like water running downhill. Just as places like Hot Springs in Madison County and Damascus, Virginia, are iconic examples of “Trail Towns” along the AT, places like Cherokee, Asheville, Blowing Rock, Elkin, and many more farther east stand to gain from the flow of thru- and section-hikers along the MST.

“I think the MST is going to be one of the country’s top trails—an extraordinarily popular hike,” says Kate Dixon, executive director of the Friends of the Mountains-to-Sea Trail (aka the Friends), which advocates and fund-raises for the trail, serves as a hub for information, and unites the 1,200-member statewide group of volunteers who build and maintain the trail.

The Vision

A burst of enthusiasm launched the MST in 1977, when Howard Lee, then North Carolina Secretary of Natural Resources and Community Development, announced the idea of a 450-mile state trail.

The task of developing the plan went to the trail’s originator Jim Hallsey, a former state parks administrator who’s since been very involved in the trail’s completion, serving as a board member for the Friends and volunteer leader with the Ashe County task force, one of many such groups across the state devoted to trail completion.

A rough 20-mile-wide corridor was proposed to run from the Smokies’ highest peak to Cherokee, north tracing the Blue Ridge Parkway, then east from Stone Mountain State Park through urban areas, from Elkin and Winston-Salem, through Greensboro and Burlington to the Raleigh area. From there, the route was to dip southeast to the coast, through Smithfield, Goldsboro, Kinston, and New Bern to Ocracoke via ferry, then northward up the Outer Banks to end atop the East’s tallest sand dune. Hallsey’s trail was approximately 1,000 miles long, rather than the mere 450 that Lee initially proposed, and it would take linking existing trails, purchasing private land, considerable funding, and many organizations working in partnership to get the job done.

“The original route planning for the MST included a lot of practical considerations, but it was inspiring too,” says Hallsey. The planners brainstormed ways “to link so many of the state’s unique natural features, public lands, small towns, urban areas, rural countryside, and remote wildlands.”

Hallsey’s efforts pushed the plan through bureaucratic hurdles and funding challenges, and the following year, Lee signed the agreement between the state, National Park Service, and US Forest Service that opened the door for trail construction to begin.

Regional task forces were formed, and some sections of the trail were designated—especially in the mountains where pre-existing trails on public lands were connected to become the MST. Though the project sputtered in the 1990s, later in the decade, supporters re-energized the effort with the formation of the Friends of the Mountains-to-Sea Trail. The designation of the route in 2000 as a state trail, a unit of the state park system, created new funding for the cause.

Given the difficulties of building a public trail across private lands in the Piedmont, the MST has been slower to take shape in the East, where some of the route still requires walking along scenic back roads. But support to see the trail become a dedicated hiking path has given momentum to the project. Just two years ago, as an alternative to paddling the Neuse River section, a land route was authorized by the NC General Assembly. Called the Coastal Crescent, the trail corridor swings past Clinton, White Lake, and Burgaw to Surf City and beyond to the Banks, connecting existing trails in widely scattered parks and public lands all across eastern North Carolina and passing historic and natural points of interest. Most trails, including the AT, evolve over time, and the MST will too. In fact, it will take more than the four decades of effort already invested to finally create and protect the entire path.

Since the early 2000s, the increasingly well-organized Friends have been surging toward that goal. Regional task forces have been reinvigorated and trail construction has exploded. Best of all, says Dixon, “the project is hitting a tipping point—the support and progress have been phenomenal.”

Segment 18 - Stretching 1,175 miles, the MST ends at Jockey’s Ridge on the Outer Banks.

Westward Expansion

The creation of the MST in Western North Carolina involved nearly a dozen trail-building crews, hundreds of volunteers, and a groundswell of funding.

By the late 1990s, significant MST trail mileage had crept along the Blue Ridge Parkway to US 321 in the High Country. But a big chunk of the mountain route—from Blowing Rock north along the Parkway to where the trail turns toward the coast—was still a dream.

That started changing in 1998 when the late Allen de Hart, a founder of the Friends and author of the trail’s first guidebook, began flagging the trail north on the Parkway. By April of 2005, work by multiple task forces, including one led by Hallsey, had begun in earnest, and the final six miles though the High Country was dedicated by Watauga Task Force leader John Lanman in 2012 with a “golden spike” ceremony near Blowing Rock.

Progress in the mountains has involved more than building new trail though; it’s created a snowball effect that’s engaged local communities and marshaled new resources.

One such example is the Burnsville-based High Peaks Trail Association, which started in 2010 with a focus on improving a neglected national forest trail system in the Black Mountains, crossing the highest peaks in Eastern America. The energetic group eventually morphed into a task force for the Mountains-to-Sea Trail, and their continuing success accruing grant money is currently helping complete a multiyear, professional reconstruction of a key piece of the MST—the historic Mount Mitchell Trail that climbs 4,000 vertical feet in 6.6 miles from Black Mountain Campground to the summit.

Similarly, in 2014, a major reroute of the Blue Ridge Parkway’s Boone Fork Trail near Blowing Rock (also part of the MST) was funded by a $75,000 grant from the North Carolina Recreation Trails Program, with another $18,750 in matching funds from the Watauga County Tourism Development Authority. The funding, which wouldn’t have been possible without consolidated community support, circumvented and closed one of the MST’s wettest, most eroded sections at Price Park and led to the creation of a dedicated trailhead parking area. And in 2016, a quarter-million-dollar, grant-funded bridge was built across Boone Fork, literally uniting portions of trail long separated by the big stream.

“In times of limited funding,” says Wright Tilley, Watauga TDA executive director, “we’re honored to be able to find grant money to improve hiking on the Blue Ridge Parkway and Mountains-to-Sea Trail. They’re consistently mentioned as one of the primary draws for visitors to our area.”

In fact, Lanman gives the Watauga TDA credit for helping jump-start the trail’s completion. “Very early on,” he says, “the WTDA got momentum going with funding that paid professional trail builders to complete a few really hard sections of trail.”

Despite all the progress, there was yet another big gap in the mountains that ultimately defied completion until last year—a stretch through the Cherokee Nation’s Qualla Boundary lands and north along the Blue Ridge Parkway to Waterrock Knob. Part of the solution was building a walkable route along the Parkway roadside with detours into the woods to bypass tunnels. The rest is seven miles of view-packed, scratch-built trail, courtesy of the stonemasons of the Carolina Mountain Club trail crew.

The task force volunteers who do the trail work are the key to completing the MST, and their participation and passion for the trail has steadily increased. Back in 2012, the Friends’ task forces devoted more than 18,000 hours to building and maintaining the trail. Last year, despite being one of the rainiest on record, MST volunteers put in 32,000 hours.

Elkin is a shining example of an MST trail town, where the path is marked on sidewalks. A mural (above right) proudly identifying Elkin as a trail town and a directional tree sign (above left) are among the signifiers.

Across the State

Enthusiasm for the MST isn’t limited to the mountains. Elkin in Surry County has re-embraced the trail town concept, bringing the MST corridor back through the center of town after it had been routed away due to lack of interest. Thanks to the formation and explosive growth of the Elkin Valley Trails Association and the rabble-rousing zeal of Dr. Bill Blackley, the path is now part of an expanding multiuse trail network, the heart of a community revitalization aimed at wellness and quality of life. Adding to the momentum, the group was instrumental in convincing a local landowner to sell a 60-acre parcel to the state containing the noted Carter Falls, now visible on the MST.

Bridges are a big part of the success story, from smaller ones connecting segments of once-separated trail to expensive and expansive pedestrian spans for downtown river walks, as seen in Elkin, and there’s a particularly noteworthy footbridge in Hillsborough. The biggest is a 150-foot bridge across a cove in scenic Falls Lake north of Raleigh, where the trail passes through US Army Corps of Engineers’ land.

That kind of infrastructure doesn’t come cheap. “There’s been a remarkable commitment from local government,” says Dixon, who adds that the “partnership model is really working.”

It might surprise mountain residents how established and enjoyable the MST is down east. In the Piedmont, there are distinctive pine and hardwood forests, rolling terrain, pastoral rural views, lively streams, and glistening lakes. On the coast are long boardwalks across subtropical marshes in Croatan National Forest, and empty, inspiring stretches of sand along the beaches of the Outer Banks.

There are many places where completed trail runs great distances. Pilot Mountain State Park, for instance, is now connected to Hanging Rock State Park. The trail passes Greensboro’s wonderful watershed lakes in Guilford County and follows the Haw River through historic mill towns in Alamance County. It runs for more than 100 miles from Eno River State Park past Raleigh and east along the Neuse River—with the city’s awesome greenway system offering almost endless connections to the MST.

Along the way are emerging trail towns where government and civic groups are funding amenities for hikers. There are places where the MST is immersed in wilderness, Dixon says, “but I envision that over time the MST will ultimately be more like a European path, with great diversity of landscapes and even small towns.” In some places the trail boasts an almost urban character with access to restaurants and lodging.

The MST’s ultimate route may not be set in stone, but no trail’s ever is. For now, it is finished in the mountains, where rock steps stand ready to lead hikers past breathtaking vistas, myriad streams and waterfalls, through rhododendron thickets or cool forested coves—or even to the Atlantic.

Visit mountainstoseatrail.org for an interactive map, help with planning a hike, info about the Friends and becoming a member, and more ways you can contribute to the cause.

-------------

MST Hiker Spotlight - Jennifer Pharr Davis

Of the more than 100 people who’ve hiked the MST end-to-end, Jennifer Pharr Davis may be most well-known. Her maiden name sounds like her hiking specialty: trekking long distances around the world and doing it in record-breaking speed. (Her 46-day, 11-hour, and 26-minute AT hike set a record.) She owns Asheville-based Blue Ridge Hiking Company, is the author of five guidebooks and hiking memoirs, was a 2012 National Geographic Adventurer of the Year, and is an inspiring speaker who trekked the MST in 2017, blogging her way across the state and helping popularize the trail.

The Asheville resident section hiked the MST over the course of four months with her husband and two small children, and found the geographic diversity afforded by the many linked trails a big part of the appeal. “Creating the MST will have such a big impact on conservation,” she says. “Linking trails together connects viewsheds and ecosystems. Separate scattered paths are great, but joining them across the state does more than just increase the recreational opportunity. A linked trail has an invaluable impact on the potential for preservation. That’s why protection of the AT has such leverage.”

Working to raise awareness of the MST, Davis spoke to students at schools across the state and realized that “many people don’t even know it’s there,” she says. The key to any trail’s impact is access, and that means proximity and awareness are crucial.

She also witnessed the educational potential of the trail firsthand. “That hike is a favorite family memory,” she says. Having reached the Outer Banks in November, she explains, “It was such a spiritual experience, with no one out on the beaches. My daughter was with me when we saw a sea turtle protection facility and then saw a sad dead turtle on the beach. Two years later, out of the blue, she says, ‘I want to start an organization that helps sea turtles,’” Davis beams. “The MST is a major learning experience that’s out there for all of us.”

Learn more about this local outdoor rock star at jenniferpharrdavis.com.

---------------

Hit the Trail - Explore the MST’s western reaches at your leisure with these great day hikes

Tanawha Trail, Beacon Heights to Boone Fork Parking

This hike crosses Grandfather Mountain’s flank, with views above and below. From an easy path to a spectacular view atop Beacon Heights, the MST wanders for 8.1 miles above the Blue Ridge Parkway, past the Linn Cove Viaduct, across the alpine crags of Rough Ridge, and through scenic spruce forests to Boone Fork parking area. Park at Beacon Heights (milepost 305.2), and the walk to Boone Fork parking area (milepost 299.9) is mostly downhill. For a shorter option, park at Wilson Creek Overlook (milepost 304.4) and the out-and-back hike to the peak of Rough Ridge is a 2-mile round-trip that avoids the crowds at Rough Ridge parking area.

Mount Pisgah, Blue Ridge Parkway MP 408

From the Pisgah Inn, the MST connects to Mount Pisgah Trail, offering a multifaceted way to see the summit. Take the MST from the left side of the inn parking area and wander the easy edge of the Blue Ridge escarpment past a few trail junctions. At 1 mile, enjoy the view and read about George Vanderbilt’s Buck Spring Lodge at the site of the former summer home. It’s another .4 mile to the Mount Pisgah Trail, where the more strenuous 2.3-mile round-trip reaches the peak for awesome views. Total hike is 5.2 miles.

Blackstock Knob, Blue Ridge Parkway MP 355-359

A scenic, 5-mile stretch of the MST traverses the spectacular evergreen forests that clothe the intersection of the Black and Craggy mountains. This hike rises above 6,000 feet and has great views at Promontory Rock. Two trailheads are 5 miles apart, so spot a second car and hike between. Start either on the Blue Ridge Parkway at Walker Knob Overlook (milepost 359.8) or on NC 128, the entrance road to Mount Mitchell State Park, (.6 mile from the Parkway at milepost 355.3 on the right).

Oconaluftee River Trail, Cherokee

Between Cherokee and the Smokies’ Oconaluftee Visitor Center, this easy graveled path wanders 1.5 miles along a dancing stream, passing a half dozen interpretive plaques with benches that movingly explain Cherokee beliefs and respect for the natural world (in English and Cherokee). Near the visitor center, the Mountain Farm Museum is a stunning collection of nineteenth-century backcountry farm structures that paint a vivid picture of the lifestyle of later settlers. Start in Cherokee to avoid parking at the busy visitor center for this 3-mile out-and-back hike.

Bluff Mountain Trail, Doughton Park

In Doughton Park, the MST embraces Bluff Mountain Trail and offers moderate hikes in forest and scenic fields. Park at Basin Cove Overlook (milepost 244.7) and the hike to the Doughton Park Visitor Center (milepost 241.5) is 4.3 miles, so you’ll want to spot a second car. Divert briefly to Wildcat Rocks Overlook to peer down at historic Caudill Cabin.

Tomkins Knob Overlook and the Cascades, Deep Gap

From milepost 272.5, north of US 421 in Deep Gap, the MST offers historic log cabin structures at Tomkins Knob Overlook, then connects north to the Cascades loop, a very nice waterfall walk. The entire hike is an easy 2.4-mile round-trip.