Monumental Matters

Monumental Matters: During a year of racial reckoning, public symbols have been renamed and removed

(Left) The Vance Monument—the obelisk at the city’s center paying tribute to Civil War governor; (Right) “Sylva Sam”—a Confederate soldier statue, Sylva County courthouse.

After the murder of George Floyd and the Black Lives Matter movement sparked national protests and global attention last summer, hundreds of buildings and monuments were renamed, altered, relocated, or removed altogether. North Carolina, in fact, has had the second most Confederacy-related monuments removed of any state in the nation (after Virginia), according to the Southern Poverty Law Center. And the mountain region is no exception, as the timeline of alterations and removals in the past year attests:

After the murder of George Floyd and the Black Lives Matter movement sparked national protests and global attention last summer, hundreds of buildings and monuments were renamed, altered, relocated, or removed altogether. North Carolina, in fact, has had the second most Confederacy-related monuments removed of any state in the nation (after Virginia), according to the Southern Poverty Law Center. And the mountain region is no exception, as the timeline of alterations and removals in the past year attests:

June 28, 2020 Appalachian State University announced that the names of two dormitories would be changed “so they may echo our commitment to creating an environment that is welcoming, safe, and respectful to our Mountaineers and to all those who visit our campus.” Hoey Hall was named for Clyde Hoey (1877-1954), a staunch segregationist who served as governor of NC and as a state and federal legislator. It was renamed Dogwood Hall. Lovill Hall, named for Edward Lovill (1842-1925), a Confederate officer who became a state legislator, was renamed Elkstone Hall.

June 29 Western Carolina University’s board of trustees voted unanimously to change the name of Hoey Auditorium, a performing arts facility, to University Auditorium. The building was also named for Clyde Hoey, whose “espoused racist views are contrary to this university’s core values of diversity and equality,” the trustees said.

July After votes by Asheville City Council and the Buncombe County Board of Commissioners, two monuments were removed from downtown Asheville: a 25-foot marker for Buncombe’s Confederate soldiers and a Robert E. Lee Dixie Highway marker. The same month, City Council ordered that the Vance Monument—the obelisk at the city’s center paying tribute to Civil War governor, state and federal legislator, and avid white supremacist Zebulon Vance—be shrouded by scaffolding and plastic covering to await recommendations from a city-county task force.

July 27 The town of Sylva formally asked Jackson County to move “Sylva Sam”—a Confederate soldier statue positioned prominently in front of the historic county courthouse—out of town limits.

Aug. 4 Jackson County commissioners voted to keep “Sylva Sam” in place but to remove the words at its base, “Our Heroes of the Confederacy,” and replace them with some yet-to-be-decided text. (At press time, the base of the monument is sheathed in plywood and surrounded by chain-link fencing.)

Aug. 28 UNC Asheville’s board of trustees voted to strip the names Hoey and Vance from two buildings—a residence hall and the campus police station, respectively.

Feb. 1, 2021 Asheville City Schools’ board of education changed the name of Vance Elementary to Lucy S. Herring Elementary—paying tribute to the late Herring (pictured above), a local legend in Black community education who served as a teacher and principal in Buncombe County for decades.

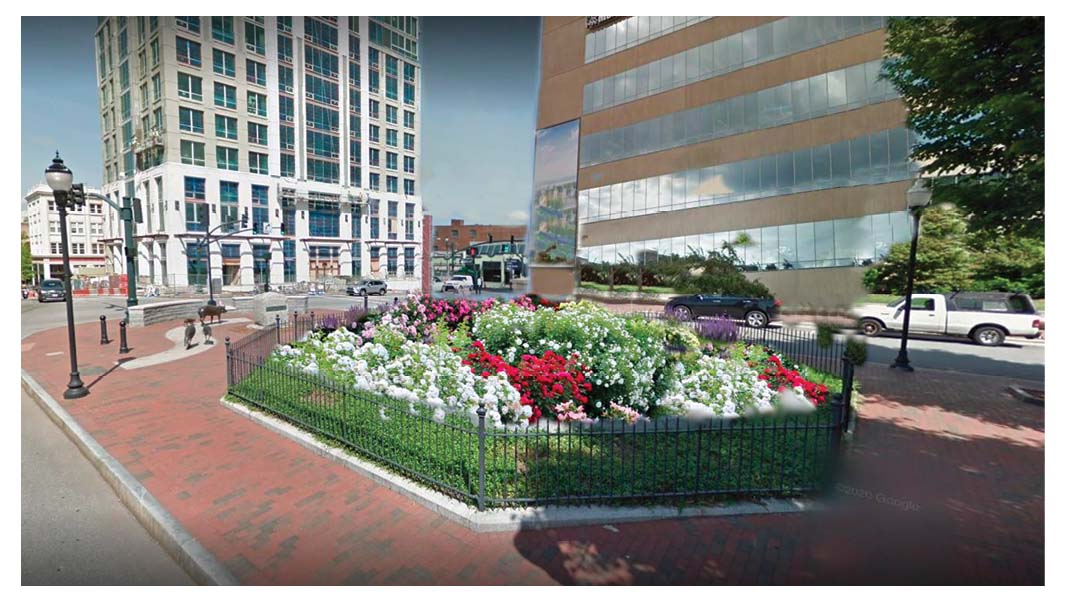

A proposed flower feature is slated to replace the Vance Monument at first.

March 17 Asheville City Council voted to commence with a plan to demolish and remove the Vance Monument, likely by early summer. The plan calls for a flower bed in the monument’s place, as a temporary installation, while a permanent plan for the space is developed.