The Little Parkway

The Little Parkway: Driving down memory lane along the High Country’s first scenic byway

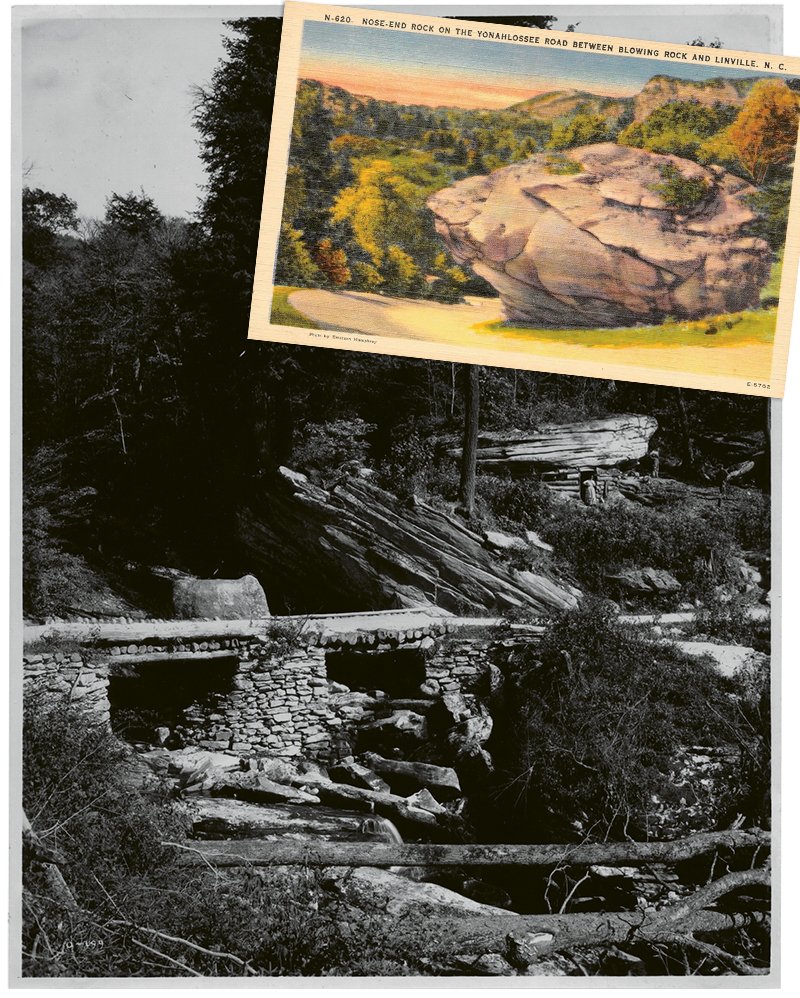

Road Trip - Along the Yonahlossee, features like Nose End Rock (postcard inset above) and the “double gusher” bridge (above) were promoted to draw tourists.

The Blue Ridge Parkway first snaked around Grandfather Mountain via the Linn Cove Viaduct in the late 1980s, but nearly 100 years prior, an equally modern marvel of engineering enticed tourists across the same mountainside.

That improbable artery was the Yonahlossee Road, and it penetrated virgin wilderness back when the High Country was barely accessible via trails and wagon tracks.

Yonahlossee Road was a 20-mile, gradually graded, spectacularly scenic route. Built in 1890, it was hailed as “the best road in the mountains” by early state highway engineers, deeming it “excellent for summer travel through one of the most beautiful and interesting portions of the mountain region.” It did nothing less than lead the earliest tourists across Grandfather Mountain, and most importantly, to Linville.

Rising Up - Completed in the 1980s, the Linn Cove Viaduct on the Blue Ridge Parkway—shown here while under construction—passes over the old Yonahlossee Road.

The road was a desperate Hail Mary attempt by the MacRae family of Wilmington to save their dream of developing Linville, one of the country’s first planned resort communities. The MacRaes had purchased 16,000 acres where Linville is today, including the loftiest crests of Grandfather and Sugar mountains, certain that the narrow gauge East Tennessee & Western North Carolina Railroad would reach Linville in time to bring hordes of well-heeled tourists from the main line railroad just over the mountains in Johnson City.

The railroad did eventually reach Linville in 1916, but in 1890, it was already clear that the new town would quickly die without some kind of lifeline to the outside world.

The only answer to the MacRaes’ question—“How are people going to get here?”—was to entice horses and buggies full of people over from Blowing Rock, which was the High Country’s first tourist town and accessible thanks to the well-maintained Lenoir Turnpike (now US 321).

Luckily for the future of Linville, building the road was, at least theoretically, feasible. The route would leave Linville at 3,800 feet and reach Blowing Rock at 3,600 feet, with very few steep spots in between. Luckier still, the terrain best suited for that elevation profile happened to lie just below Grandfather’s most formidable rock formations—the very boulders and cliffs that a century later would dog builders of the Blue Ridge Parkway and dictate the Linn Cove Viaduct’s leap away from the mountainside.

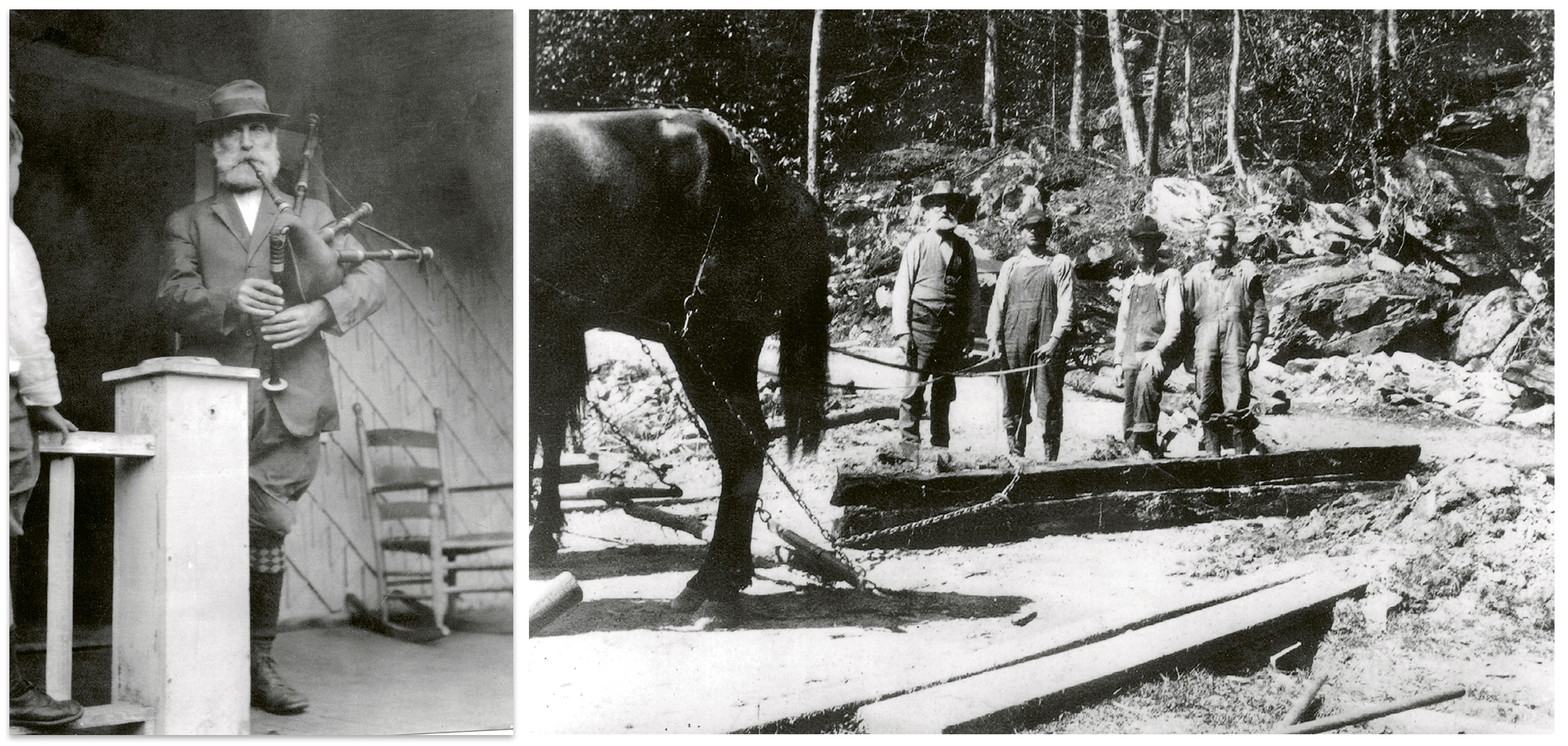

Motley Crew - Bagpiper Alick MacRae (left), along with a cadre of mountain men (right), used brute force and horse-drawn equipment to construct the Yonahlossee Road, which was at the time considered to not only be the mountains’ best road, but an adventure to be experienced.

Enter Alick MacRae and Joseph Larkin Hartley. Miraculously, Alick was not one of the Wilmington MacRaes, but another MacRae already living at Grandfather Mountain. This Highland Scot was renowned for playing his bagpipes beneath Grandfather’s peaks and was living in his namesake MacRae Meadows a full 70 years before the now-annual highland games would come to those same fields in the mid-1950s. Joseph Hartley, later Squire Hartley to Linville’s wealthy summer set, was a classic, craggy faced mountain man whose descendants were destined to play key roles in Linville and at Grandfather Mountain to the present day.

The challenge of building the Yonahlossee Road fell to Alick, and Joe was one of a crew of up to 100 men who worked entirely by hand, excavating a road up to 14 feet wide with picks and shovels, oxen and mules. The total cost was $18,000, and the project took about a year.

During construction, Joe’s son, Robert Hartley (manager of the Grandfather attraction in the 1970s and ’80s), said his father “got 65 cents a day and gave Mrs. MacRae 30 cents a day for his room and board,” at the MacRae House, close to the work site. Joe Hartley said, “It was really something to build, through as rough and rugged a country as you’ll find. ... Hewing and grubbing from daylight ’till dark six days a week. Oh, but it was a marvel to behold.” In addition to being eye-catching on its own, the road’s creation was noteworthy for how little it disrupted the surrounding landscape. For example, in her classic book, The Carolina Mountains, Margaret Morley praised the road for “scarcely changing its grade for a distance of nearly 20 miles.”

Yonahlossee Road’s scenery included named roadside attractions, among them Nose End Rock, projecting its proboscis over the road; Stack Rock (or Leaning Rock), a massive, tilted pillar; and Bridal Veil Falls, a cascade that leaps off a rocky roadside slab. Grandfather Mountain towered above it all, and the road surveyed the Piedmont far below.

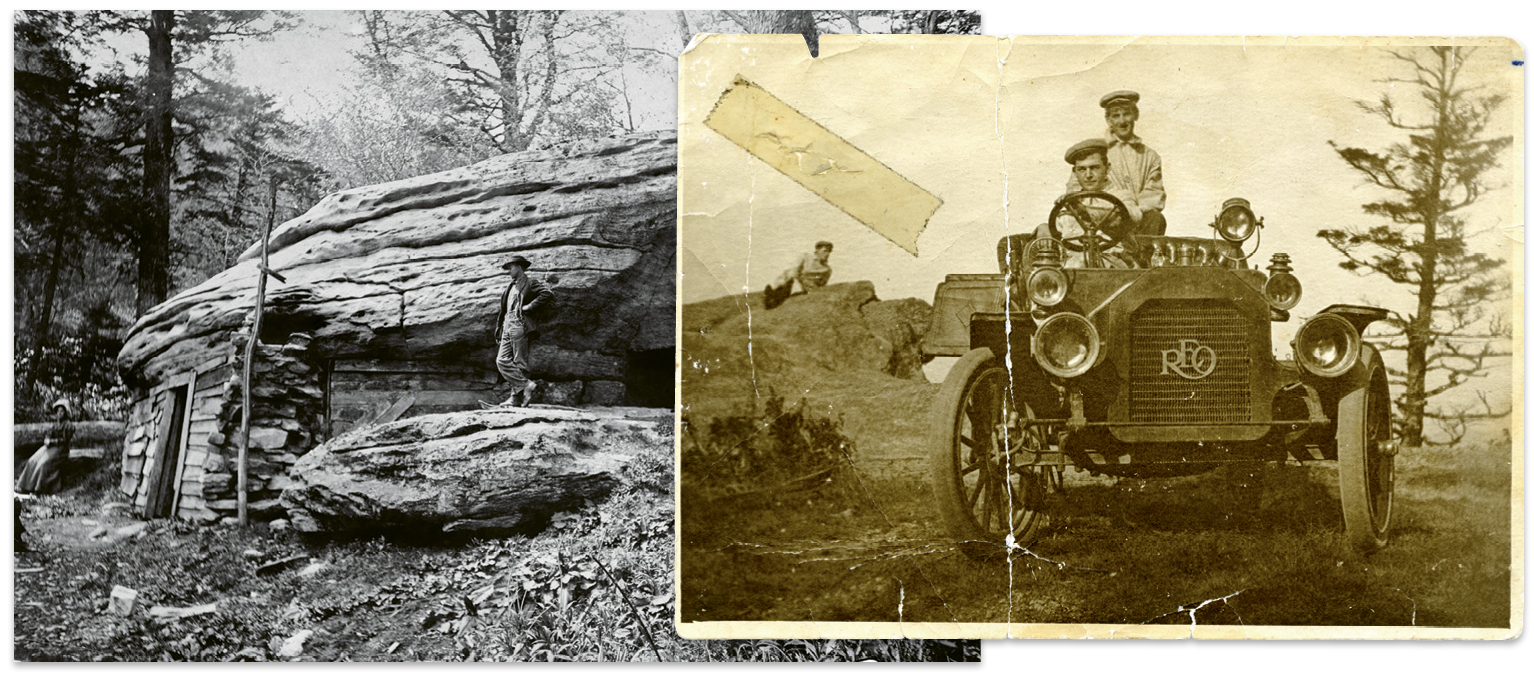

Trail Blazers - In 1909, James Shuford and friends (right) were the first people to journey along the Yonahlossee in a motorized vehicle. The rock shelter (left) offered travelers photographic opportunities.

But the Yonahlossee Road was more than a tourist route. It pierced the area’s isolation and became popular with locals as a direct path to walk or ride to neighbors’ homes and distant stores. It would remain the fastest way to get from Linville to Boone until the 1950s. The road also offered easier access to longtime extractive activities, such as hunting, gathering berries, and pulling galax to sell as floral decorations.

No matter what drew travelers to the Yonahlossee, the route was long and it wasn’t unusual to see people pulled off, picnicking, cooking over a fire, or camping. The scenic stone bridge across Wilson Creek was immortalized in many a photo, as was the massive boulder beside it that mountain locals called a “rock shelter.”

For a time, the sheltered area beneath the rock was enclosed with stone and wood to create a sort of cabin, a rustic refuge often relied on by High Country hunters, gatherers, and even guides leading early explorers and scientists. It’s likely that this landmark was one of many used by Civil War deserters and escaped prisoners, including one Union officer who described suffering mightily there during a snowy 1864 stay while fleeing to Union lines in east Tennessee.

Howard Byrd of Foscoe still remembers the days when the Yonahlossee Road led to riches plucked from the flanks of the mountain. “A lot of times,” Byrd says, “we’d go around there one morning, camp under one of them big rocks, and pick blueberries plum to the top of the Grandfather before they ever thought about building that Swinging Bridge. I slept behind that rock many a time, yes, sir.”

Linville would struggle into the mid-twentieth century while the Yonahlossee Road’s attractions remained easy out-and-back adventures from Blowing Rock, which boasted Yonahlossee landmarks on its postcards as a draw for tourists.

Moving Forward - Today, Yonahlossee Road is known as the Little Parkway Scenic Byway and is popular among cyclists. Together with the Linn Cove Viaduct on the Blue Ridge Parkway (seen in the background), both roads continue to offer travelers function and beauty.

By the 1930s, the road was finally paved, and is still in use today as US 221. Before the interstate highway system, paved roads in many parts of the country were linked to create informal “trails” by tourism interests to encourage long-distance travel. US 221 became part of a recommended route from Canada to South Florida called the Black Bear Trail, and plaques along the way—including one on Nose End Rock—displayed the namesake mascot.

It was a fitting, if not ironic, “trail” moniker considering the Yonahlossee Road had earned its name from an even earlier Cherokee path along that same side of the mountain that translated to “Bear Trail” or “Passing Bear.”

When the plans for the Blue Ridge Parkway were being developed, the Yonahlossee Road almost became part of the route, but the National Park Service declined, saying it wasn’t scenic enough. Ultimately the Parkway and Linn Cove Viaduct were built high above the Yonahlossee, though during the decades when the new road was under construction, US 221 was the official Parkway detour.

It’s hard to believe that, so long ago, the 1890s scenic attractions of the Yonahlossee Road enjoyed the same iconic status now showered on the viaduct portion of the Parkway. Today, North Carolina has designated the old highway the Little Parkway Scenic Byway, and indeed, a loop of the Parkway and Yonahlossee Road create a uniquely historic and scenic sojourn.