The Happy Land

The Happy Land: Former slaves forged a communal kingdom in Henderson County

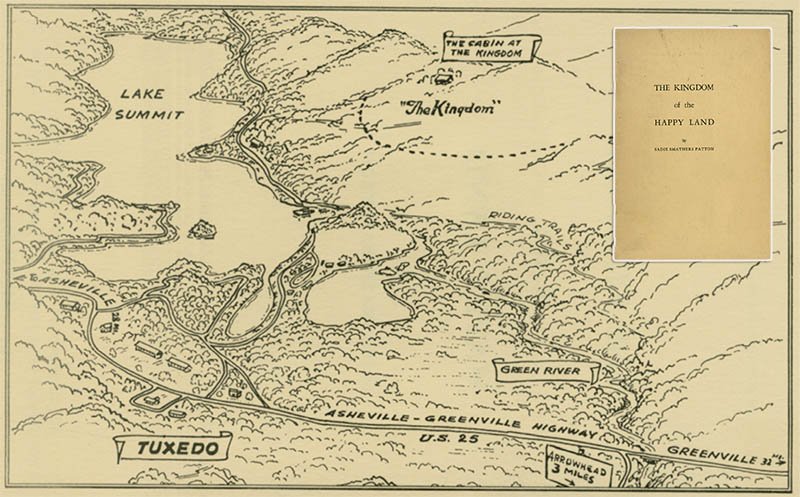

Much of what is known today about the Happy Land was first published in Sadie Smathers Patton’s 1957 booklet (inset above), which included a map (pictured above) showing where the kingdom was situated in relation to present-day Tuxedo and Lake Summit.

It began, the stories say, with a search party of sorts: a caravan of emancipated African Americans traveling up from the Deep South, looking for a place where they could embrace freedom, safety, and self-sufficiency—a haven for putting down roots and building a new life. They found it in the southern reaches of Henderson County, where they established the Happy Land, or perhaps the Kingdom of the Happy Land—accounts differ on the precise name. For decades following the Civil War, a singular communal experiment existed, and it became the stuff of legend.

Chronicles of the Happy Land have proved as divergent as the paths that brought those freed slaves to their destination. Little of their venture was written down at the time, but stories added to the record decades later have helped paint a picture of how the kingdom’s residents came to their unique way of living, how they prospered, and how their saga was ultimately cast to the winds of history.

Unearthing the kingdom is an exercise in finding and compiling rare and distant records. The account that follows is chiefly drawn from three sources, each offering partial but intriguing details on the Happy Land.

A state road sign for Kingdom Place, near Tuxedo, is one of the few contemporary testaments to the Happy Land.

Kingdom Makers

The first source is a 20-page monograph, The Kingdom of the Happy Land, that was published in 1957 by the late Sadie Smathers Patton, a Henderson County writer and local history enthusiast. Some historians have disputed details in Patton’s account, but it was drawn, in part, from interviews with direct descendants of Happy Land denizens. That, along with the general paucity of published information on the subject, has made her version an oft-cited one; what’s more, the broad strokes of her telling share similarities with the few other existing versions.

According to Patton, the band of former slaves that settled the Happy Land struck out from Mississippi as the Civil War drew to a close. As they passed through Alabama and Georgia, their numbers grew, with word spreading that they sought an idyll in some unknown northward locale. When they reached South Carolina, “their visions were brightened with a new focus” and “hope that their journey was nearing its goal,” Patton wrote. There, they learned from others recently liberated, that Lowcountry white folks had long found comfort.

In Western North Carolina’s higher elevations—“mountains that stretched for miles without habitation, where newly freed slaves might find a small piece of land to call home.”

After scaling the steep trade route across the state border by horse and wagon, the entourage encountered Serepta Davis, the widow of Col. John Davis, who had farmed swaths of south Henderson County on his plantation, Oakland. The white woman, in dire need of help to work the land, agreed to transfer a portion of the Davis land to the Black refugees in exchange for labor, and ultimately sold them 180 acres at one dollar per acre. Wandering no more, they began to establish the Happy Land, in a valley and on ridges overlooking the Green River around what today is Lake Summit and the town of Tuxedo.

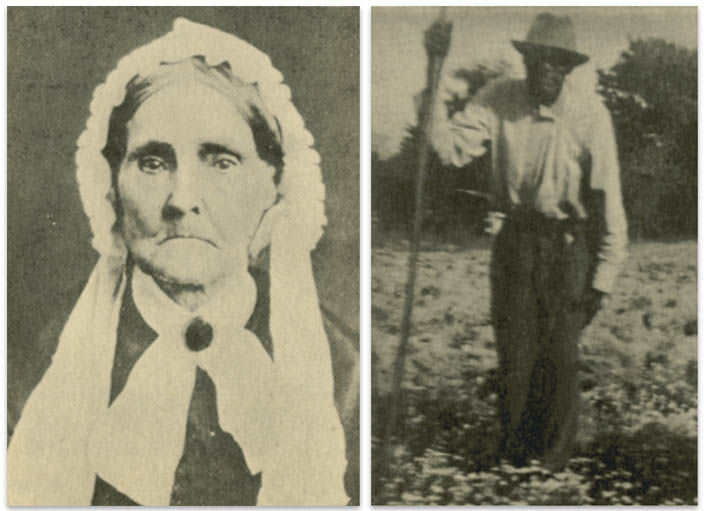

Serepta Davis (above left) welcomed the group of freed slaves and sold them 180 acres. (Right) Ezel Couch, shown here in a photograph from Sadie Smathers Patton’s study of the Happy Land, was brought to the kingdom in 1873 at age one. He died at his home in Hendersonville in 1961.

Patton estimated their early numbers at between 50 and 200, but acknowledged it was at best a guess. “There seems little doubt, however, that after the first years, those who lived in the settlement were governed by rulers known as the King and Queen,” she wrote. They came to practice what she called “a strange and primitive form of collectivism” wherein “each man and woman filled each daylight hour with the common task of developing a new world for all,” pooling their resources and distributing them as the “royals” decided.

Who, exactly, ruled the Happy Land? Patton found some clues, at least for key stretches of the kingdom’s existence. In the 1870s, she wrote, a resident named Robert Montgomery emerged as the king, with his sister-in-law, Louella, serving as queen. The Happy Land in fact straddled the state border, with Robert living on the North Carolina side and Louella living just yards away in South Carolina. Louella, Patton wrote, “appears to have been the dominant and moving spirit in the little communal settlement of this period.” She taught the children and led the residents in worship and singing. “White people living in the surrounding community long remembered the pleasure the Kingdom singers provided,” Patton recorded.

Whatever the precise nature of the unorthodox living arrangement, the Happy Land apparently bore fruit for its residents, Patton wrote. “Surplus food stuffs raised on the new farms were carried to available markets, women not engaged for housework, cooking, and serving meals found employment in caring for the sick or for young children; spinning, weaving, and knitting proved profitable.” What’s more, the kingdom became a source of medical treatments like Happy Land Liniment, used to soothe rheumatism and other aches, and “herbs with curative properties.”

For a few decades, at least, the kingdom thrived as one of the only independent enclaves of its type in the American South. But then, almost as suddenly as it appeared, the Happy Land became a veritable lost colony.

Hendersonville native Ronnie Pepper shares little-known stories of Henderson County’s Black history, including the remarkable tale of the Kingdom of the Happy Land. Hear an audio recording of his take at conservingcarolina.org. Previously, accounts by white writers, like a 1957 Asheville Citizen newspaper series by John Parris, above, were the most prominent sources on the matter.

Keeping it Alive

In Patton’s telling, the arrival of the railroad in the 1880s began an extended period in which “the kingdom broke up.” As this new form of transportation and commerce changed the whole region, so too did it uproot the Happy Land’s little economy and way of life. Families from the commune began to depart for work in Hendersonville, Flat Rock, Upstate South Carolina, and other locales.

As their numbers dwindled, white families bought out the few remaining parts of the kingdom, and by 1900, little of the enterprise remained. “Jerry Casey, the last member of the colony remaining at the Happy Land, died in 1918, at an old house that was said to be the former Robert Montgomery home,” Patton wrote.

With scant written records of the kingdom’s existence—just a few, hard to parse deed and genealogical records—what we know of the Happy Land today is cobbled together from scattered, latter-day interviews. Some of the key ones were gathered in another rare source: a 1985 issue of Echoes: Reflections of the Past, a journal compiled by enterprising students at Northwest Middle School in Travelers Rest, SC.

The students and their teachers spent months tracking the history of the Happy Land, visiting its former location and speaking with descendants of residents and those who replaced them. A Hendersonville resident, Ernest Mims, related tales passed on from his great-grandfather, Perry Williams, who had lived at the kingdom.

“Now the odd thing about it was that my grandmother would visit [the former commune], but no one would want to be tied to the Kingdom of Happy Land,” Mims told the students. He thought the association might be a source of some embarrassment. “From what my grandmother told me, it was sort of thought that they were looking for the promised land”—that, perhaps, the Happy Land sought too much of a utopia and unraveled due to its residents’ naivete.

Still, the saga of former slaves seeking, and for a time finding, their own earthly paradise has held strong sway through the years. A third key source is Ronnie Pepper, a Hendersonville storyteller who delights in sharing his imagined retelling of how the Happy Land came and went. In 2019, the local nonprofit Conserving Carolina recorded his account for posterity.

According to Pepper, the people who established the Happy Land had much to be proud of, but it should come as no surprise that their bold experiment faced difficult odds. After all, the white supremacist order didn’t disappear with the end of the Civil War. “Think about it,” he said. “You got a group of people that were free, but yet they weren’t educated as far as what the law was, paying taxes [on the land]. … Think about that, if they had to go pay the taxes and someone says, ‘Wait a minute. You can come in the courthouse? You own land? Hmmm.’ How hard would it be to get good answers if somebody didn’t want you there?”

Wanted or not, the kingdom’s residents were there, and their legacy lives in stories passed generation to generation as much as in written records. “That’s just why we need to keep it alive,” Pepper said, “and keep talking about it and remembering it.”