Future of the Forests

Future of the Forests: As the Nantahala and Pisgah national forests face a historic turning point, the planners are impassioned and the stakes are high

A hiker marvels at Douglas Falls in the Big Ivy section of Pisgah National Forest.

On any warm summer day in the heart of Pisgah National Forest, dozens of swimmers of all ages are usually lined up and ready to plummet on their rear ends down a 50-foot natural granite water slide into a pool of eye-poppingly cold water. The slick rock, on the Davidson River near Brevard, is steep enough for a thrill but not sheer enough to be reckless—and an impressive signifier of nature’s ability to not only devise complex ecological systems but also provide world-class recreation.

This water park is free from the usual trappings of a tourist draw. No piped-in music. No sticky snacks, trinkets, or adult beverages for sale. Still, the nature-built slide requires serious resources: lifeguards, trash collectors, and parking attendants, just for starters. In fact, the Sliding Rock Recreation Area is among the most-popular destinations in one of the most-visited national forest systems in the United States.

Venture beyond the roadside attractions and you’ll find huge swaths of wild terrain and towering hardwoods, rare wildflowers, sparkling streams, and fish and wildlife in Western North Carolina’s two national forests—the Pisgah and the Nantahala—which together encompass over one million acres and span 18 mountain counties.

Driving through the area, hiking a trail, casting for trout, or sliding down a creek on your fanny, you’d have little indication that these forests are nearing the completion of an unprecedented planning process—one that will have decades of impacts. In February 2020, nearly 40 years after legislation stipulated that the public be engaged in national forest planning and almost a decade after the launch of this planning process, the USDA Forest Service unveiled the Proposed Nantahala and Pisgah National Forests Land Management Plan to steward these precious resources.

Is the plan a voluminous bureaucratic opus destined to be read only by an exclusive circle of specialists and authorities? Perhaps. But the hundreds of pages of analysis and public opinion were devised not only by scientists and government experts, but by an unprecedented outpouring of public interest from the very people that live near and use the forests.

In fact, the future stewardship of the Pisgah and Nantahala national forests will not rest solely on the shoulders of a century-old federal government agency; it will be aided by a network of organizations made up of horseback riders, hunters, climbers, and wilderness lovers, to name a few. Their missions vary, but all of their values are deeply tied to the public forests of Western North Carolina.

“This planning revision process has set the stage for a meaningful private and public partnership of groups and people who are deeply invested in providing manpower and resources to get more accomplished in our national forests,” says Lang Hornthal of EcoForesters, a nonprofit forestry organization based in Asheville.

And it couldn’t come at a more crucial time. In the early part of the 20th century, the resurrection of Western North Carolina forests, long plundered by timber companies, was heralded by some as an enormous environmental victory. Today, however, the struggle to protect the land from industrial-scale logging is over. Instead, attention is focused on how to manage public forests for a wide range of uses, including sustainable timber harvesting, recreation, conservation, and wildlife habitat, among many others.

Yet given the historical, ecological, and economic importance of the two forests, deciding exactly how to manage their future is no simple task. Whether you harvest wild plants or timber for a living, hike trails, hunt for turkey, or enjoy wildflowers or mountain views, you have a stake in how the national forests are managed, and you should pay attention to this process.

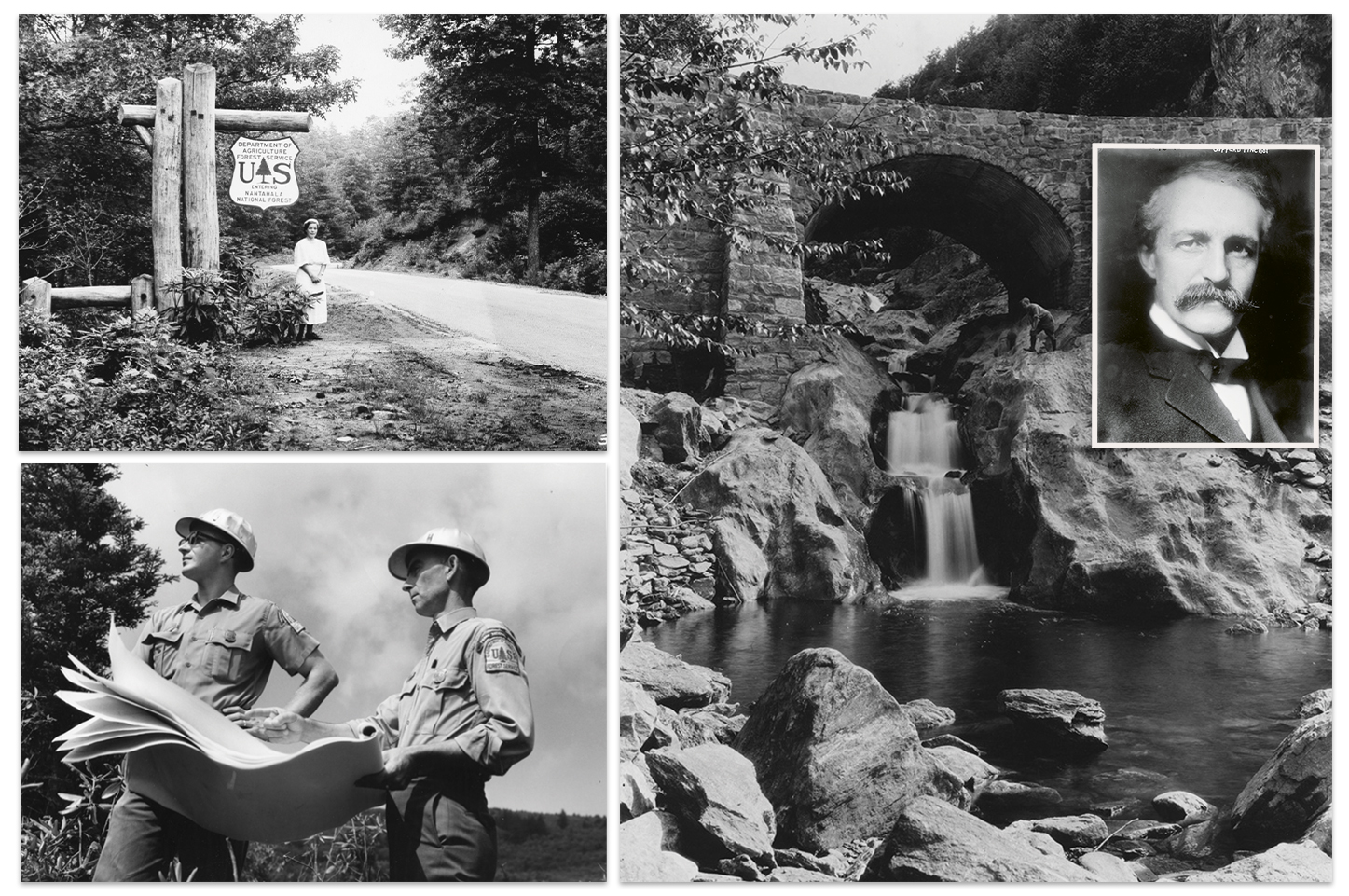

Gifford Pinchot (inset) was an early advocate of practicing scientific forestry in WNC and around the nation; in 1905, he became the first chief of the new United States Forest Service. Right, a Forest Service bridge above Sunburst Falls in Pisgah National Forest. Bottom left, Forest Service surveyors scope out a road project in the mid 1960s. Pisgah, established in 1916, was one of the first national forests in the eastern US.

Pinchot’s vision

In 1892, Gifford Pinchot arrived at the train depot in Asheville to oversee the wooded domain of George Vanderbilt’s vast estate, stretching from his castle-in-the-works to the conical apex of Mount Pisgah 20 miles upland—much of it damaged, heavily grazed by free-range cattle, and burned by wildfire. The high-minded, Yale-educated forester believed that “scientific” forestry could not only produce timber for a rapidly industrializing nation, but that forests could be managed for future generations, too.

Pinchot didn’t stay in Asheville long. But, in the following decade, he would again oversee portions of North Carolina’s timberland, including forests once owned by Vanderbilt and sold to the government, only this time as the nation’s first chief public forester. Among President Theodore Roosevelt’s most-trusted advisers, Pinchot led a crusade to protect against what the two considered the plundering of the nation’s vast natural resource. The forests of the US, Roosevelt asserted, “should be set apart forever for the use and benefit of our people as a whole.”

Those words formed a prelude to the formation of a federal forest agency. Organized in 1905 and led by Pinchot, the US Forest Service was created to manage 21 million acres of forests in the West. Soon, the agency looked east, where forests were in dismal shape due, in part, to industrial-scale timber harvests and a blight that erased the American Chestnut from the landscape.

Today, the region and its land managers face an entirely novel set of challenges that were unimaginable to Pinchot and Roosevelt, from global warming to escalating recreational demands.

A big opportunity

“Wherever you are in Western North Carolina, public lands are always in the backdrop, forests are always in view,” says Jill Gottesman of the The Wilderness Society. “We’re the next generation of people stewarding the land, and this is one of our biggest opportunities to guide the management of our backyard.”

In 2013 Gottesman helped form the Nantahala-Pisgah Forest Partnership, which included an array of recreational, economic, government, and conservation organizations eager to discuss a range of forest issues in preparation for the start of the plan-revision process that began in November 2012. (Each national forest is required to have a management plan renewed every two decades; a single plan for WNC’s two forests was approved in 1994.)

The NPFP’s objective has been to provide guidance in creating the best forest plan possible and to restore the two forests’ ecological health and economic sustainability. It is one of several collaborative entities that have formed or been active during the planning process, including the Fish and Wildlife Conservation Council, the Pisgah-Nantahala Stakeholders Forum, and I Heart Pisgah.

But bringing people together with conflicting interests is never easy. Hornthal acknowledges that managing conflict among special interests is ever present in forest planning, but says that disagreements and alignments of various users and interests is far more nuanced than you’d expect. For example: you probably wouldn’t suspect that those wishing to extract timber for profit and those that desire the protection of old-growth forests actually agree on something, but they do.

In fact, despite the presence of discord, there is at least one crucial zone where multiple groups with conflicting interests meet: the ecological restoration of the forests. That is, using science and techniques to direct the recovery of an ecosystem that has been degraded or damaged by creating conditions that plants and animals require to thrive. In some cases, restoration may involve leaving a forest completely alone; in others, it entails prescribed fire or timber clearings to replace spontaneous natural disturbances once caused by wildfire.

“There’s a lot of interest in making parts of the forest younger and making parts of the forest grow older for many different reasons and values,” says Kevin Colburn, a member of the NPFP’s leadership team and stewardship director of American Whitewater. “One of the nuances we found is that ecological restoration as a concept meshes with pretty much everyone’s values whether you shop at REI, Cabelas, or both.”

Tradition and transition

Of course, there are a few groups that were here long before Pinchot and his lofty ideals about how to manage forests. Tommy Cabe represents one of them: the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians. “We may be tucked in this corner of Western North Carolina, but we are still here. We’ve survived,” says the EBCI’s forest resource specialist and partner of the NPFP. “There’s an opportunity for us to engage and to demonstrate our philosophy on landscape management.”

A chief example is how to harvest and sustain ramp populations, a wild onion that Native Americans have harvested for thousands of years. It’s just one of many nontimber forest products, from ginseng to galax, that Native Americans and others gather for food, medicine, and crafts, or for spiritual or commercial reasons. Over the last several years, the bold-tasting green has become wildly popular among foodies, and its rising economic worth has increased pressure on harvesting.

Of course, other rural communities throughout the mountains rely on the national forests and its precious bounty to sustain their economies, too. Take Graham County and its seat, Robbinsville, nestled in the state’s far southwestern corner. The county has struggled to find an economic foothold since its worst setback in decades, when Stanley Furniture shuttered its plant and shed over 300 jobs in 2014, a devastating hit for a town of around 600 residents.

Sophia Paulos, the county’s economic director, says that lumber production “helps to maintain the cultural tradition of working with the forest to earn a living.” While other rural western counties have attempted to influence the forest plan revision, most have operated at the fringes of the planning process. Paulos however, jumped on the opportunity and joined the NPFP. “I immediately saw the forest plan as crucial to Graham County,” says Paulos. “Whether it’s tourism or timber, our economy is dependent on the forest. It’s a part of us. So I felt like it was very important for us to be at the table.”

While county leaders hope to revive the timber economy, the future of the county’s nearly 9,000 residents remains heavily linked to the resources within Nantahala National Forest, with or without lumber production. Increasingly, tourism and recreation may drive it.

However, recreational demands are pressing down hard on points in many parts of the forest, whether it’s crowded mountain bike trails near Asheville and Brevard, campgrounds, popular streams, or other heavily used recreational assets. The crux, says Hornthal, who serves as the chair of the NPFP leadership team, is “how to add and manage more infrastructure when the agency is having a tough time maintaining what they have now” due to shrinking federal budgets and staffing.

One approach, for instance, is a management strategy promoted in the plan by the Forest Service that divides the region into 12 geographic units that highlight specific uses and focused management practices as they relate to the three themes of the plan revision: restoration and resiliency, providing clean and abundant water, and connecting people to the land.

Another approach in the draft forest plan is to identify “special interest areas,” a designation that recognizes places with significant public interest. Among the proposed areas is acreage in Buncombe County near the Blue Ridge Parkway that includes the Big Ivy watershed and the peaks of the Craggy Mountains. The group I Heart Pisgah wants the Forest Service to take it a step further and is proposing the area be protected as the Craggy Mountain Wilderness and National Scenic Area, encompassing 16,000 acres. Additions to the National US Wilderness Preservation System and national scenic area designations offer a higher level of land protection, requiring a recommendation from the Forest Service and approval by Congress and the president.

“Having a national scenic area 15 miles from Asheville would be an exciting development for the entire region and protect the values people have for this area,” asserts Will Harlan, an organizer of I Heart Pisgah. “The area has a great mountain biking trail network, hundreds of acres of old growth, clean water, rare species, and is arguably one of the most valued viewsheds in the nation.” Their proposal, says Harlan, is based on the public comments of hundreds of people who wish to see the area protected forever.

While the final plan will not be unveiled until 2021, the draft includes four potential alternatives to manage the forests. By law, the draft requires a 90-day public comment period featuring public meetings that were postponed by the COVID-19 pandemic. Forest Service planning officer Michelle Aldridge says the “alternatives were designed based on shared values we heard from our partners and the public to offer win-win solutions and minimize polarization. Collaborators specifically asked the Forest Service to design alternatives that would unite interests, building upon shared values, rather than send folks back to their corners to advocate for single interests.”

Among the innovative structures of the plan is the adoption of “tiered objectives.” The strategy initially targets modest goals for each forest plan objective, such as the number of miles of trail improvements, and only stretches to more ambitious objectives once the needs of other stakeholders, such as timber-harvesting interests, are met. The hope is to incentivize forest users to collaborate rather than fight, and nurture future partnerships.

Hornthal points out that the focus of the collaborative work during the planning process has been, in large part, to reduce conflict. Ultimately, however, he and others have a desire to rise above the fray and focus energy on resolution of some of the forest’s most pressing challenges, such as battling exotic plants and pests, repairing a backlog of damaged trails and roads, nurturing local economies, restoring delicate habitats, and adapting to a changing climate.

By the time the plan is finalized in 2021, its creation will have spanned a decade. While a bureaucratic document 10 years in the making may seem excessive, on an ecological timeline, it’s faintly perceptible.

In fact, how we steward the land now will matter for a long time to come, says Cabe of the EBCI, whose ancestors championed a sweeping view of nature. “We’re taught not to decimate the landscape, otherwise it will affect our bloodline for seven generations. That’s a long time, but that’s how we regard the land. That’s how we’ve always regarded it.”

Drafting an effective plan that encourages harmony is more crucial than ever, says Hornthal, in order to sustain the transformation of the mountain forests from an ecological apocalypse to an indisputable environmental triumph.

“Our forests have been neglected, and now is the time to do something,” he says. “We’re all in this together.”

(Clockwise from left) Dry Falls in Macon County, one of Nantahala National Forest’s renowned scenic spots; Mountain biking and fly fishing are but two of the outdoor pursuits that help draw hundreds of thousands of visitors to the national forests each year. Top, biking in Pisgah; above, fishing near Pisgah’s Davidson River Campground

What’s Next?

The forest planning process is winding down but far from over. The release of the proposed plan was accompanied by a draft environmental impact statement, which evaluates the impact of each proposed management alternative and presents the possible trade-offs of what might come with them.

A 90-day public comment period followed the release of the draft EIS. That process commenced in February, but was delayed by the pandemic and has been extended to June 29. In addition, several public meetings were cancelled, but the Forest Service has created a “virtual open house” online to share vital information (find it at bit.ly/WNCforests).

Moving forward, the Forest Service will respond to public comments in the fall of 2020, and present an updated plan and final EIS in the spring of 2021. Following a five-month objection period, the agency will review any unresolved objections, and it estimates the release of a finalized plan in late 2021.

Editor’s note: This feature was sourced in part from the writer’s extensive reporting for Carolina Public Press, an Asheville-based nonprofit news service.