Fear Factor

Fear Factor: Every rock climber starts life as a gravity-respecting mortal

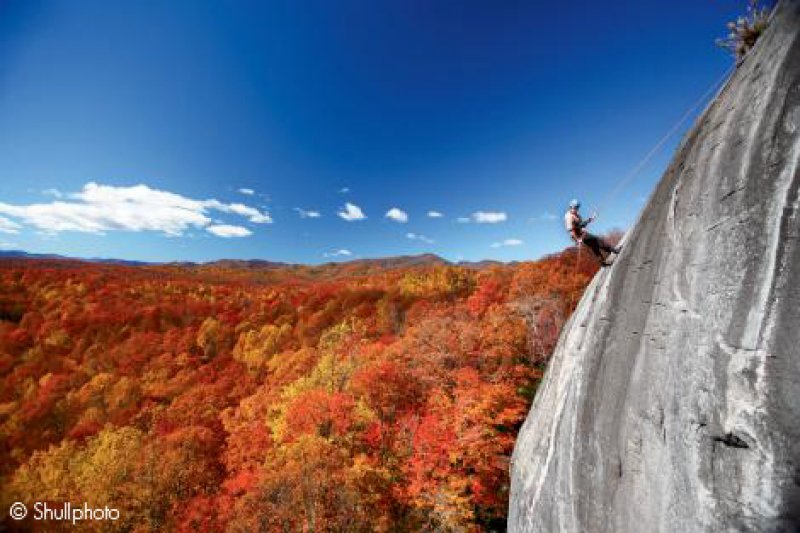

That’s the question I keep asking myself as I scale the vertical stone face of Cedar Rock in Pisgah National Forest. Perched halfway up the side of this granite mountain, I’m vaguely aware of the gaping views of forested peaks that stretch for miles around me—views most rock climbers would be languishing in—but I’m too preoccupied with my placement on a fictional bravery scale to enjoy the sights.

On the überbrave end of the scale, you’ve got The Great Blondin, a French tightrope walker famous for cooking an omelet while hovering over Niagra Falls on a wire. On the opposite end of the bravery scale, is the agoraphobic poet Emily Dickinson, who refused to meet face to face with visitors. Instead, she’d shout at them from behind a closed door upstairs.

As my right toe slips from a minute ledge that was previously holding the entire weight of my body, and my left hand reaches in vain for the closest jagged rock that would save me from a disastrous fall, I have to wonder, “am I The Great Blondin or am I Emily Dickinson?” If I’m being perfectly honest, the life I’ve led up to this point has leaned more toward the poetic. I have no trouble greeting visitors, but one time I did get a rash from using too much hand sanitizer at an outdoor festival.

But my fear of falling at this point is a tad overdramatic. I’m wearing a safety harness that’s attached to a rope rated to hold more than 3,000 pounds. Really, I don’t even drop. I just swing out from the rock a little bit, and then smack back into it. In maybe five seconds, I’m safely poised on the wall again, my hands gripping small nubs of stone sticking out of the rock face, my left foot wedged in a wide crack.

I take a deep breath and reassess my situation. I’m still alive and feeling slightly more confident, but I’m also still only part-way up a route that demands I follow a crack in the granite wall for 50 feet before pulling myself up an overhanging ledge. The crack is draining last night’s rainfall, so it’s more of a water feature than a climbing route. The air is chilly, my hands are numb from the cold water, and there’s a flap of skin dangling from my elbow thanks to my collision with the wall. I really don’t think I can make it up the route, but I’m eager to keep climbing. Even more surprising: I’m having a good time.

Take a cursory survey of the mountains of Western North Carolina, and you might think there’s not much rock to climb, but you’d be wrong. Sure, the ridgelines are covered with hardwoods, but interspersed between these lush peaks are granite formations like Looking Glass Rock, Rumbling Bald, and Cedar Rock—big, gray humps and cliff banks. Add to that the massive rock chasms of Linville and Hickory Nut gorges, as well as the smaller cliffs and satellite crags such as Bradley Falls and Snakes Den, and you’ve got a bevy of climbing options.

Not that I gave a damn about rock climbing until a few months ago. I only started climbing to prove to myself that I can. Face your fears, carpe diem, that sort of thing. I never expected to actually like the sport. There’s a laundry list of reasons why I wouldn’t, beginning with a fear of heights and ending with the fact that I have the upper body strength of a duck (please note the duck’s complete lack of an upper body). Basically, it boils down to an overdeveloped sense of self-preservation. Climbers go up when the law of gravity insists they stay down.

“Rock climbing is counterintuitive,” says Jessa Goebel, a Boone-based professional climber who owns Climb Fit, a training program for rock hounds. “But football is counterintuitive, too. Big people running right into each other? That sounds dangerous to me. At least in climbing you have greater control over the safety factors.”

Ah, the safety factors of rock climbing: ropes, harnesses, top rope anchors, belay devices—all of which are rigorously tested by manufacturers to ensure the gear climbers use could hold an elephant in the air if necessary.

Most climbers start by top roping, which is the simplest, and safest technique. A rope is threaded through an anchor at the top of the cliff, then attached to the climber using a figure-eight knot. The belayer, a person standing at the base of the cliff, is attached to the other end of the rope through an Air Traffic Controller (a piece of equipment that attaches to the belayer's harness, allowing them to control the rope). You’re basically creating a human pulley system. As the climber ascends the rock, the belayer takes slack out of the rope, so when the climber falls, he doesn’t drop. It’s a simple way to eliminate some of the fear and introduce mortals like me to the sport. Still, it took me a while to accept the idea that I am perfectly safe suspended 100 feet above the ground by some nylon webbing, a tiny metal clamp, and a belayer who swears he has my best interests in mind.

My first climbing adventure took me to Rumbling Bald, a popular crag inside the newly designated Hickory Nut Gorge State Park. Hundreds of routes ascend this cliff, which stretches across a mountain overlooking Lake Lure. As with all crags, each route has a colorful name, like Mid-Life Crisis and Comatose. During my brief tenure on the route less-menacingly dubbed Fruit Loops, I was so convinced my knot was going to unravel that I spent a good eight minutes hugging the rock while the nice guy who agreed to take me climbing tried to talk me down. I was only 20 feet off the ground, but in my mind, I was hanging off the side of El Capitan.

The second excursion demanded I rappel off a 100-foot cliff next to Big Bradley Falls in the Green River Gamelands. I became increasingly soaked by the mist from the waterfall as I lowered into the boulder-choked gorge. The rappel was so intense, that climbing the cliff afterward was almost mellow, as if I’d shocked my system into handling the heights. Each subsequent trip up the rock became less nerve-wracking, allowing me to focus more on the act of climbing and less on the threat of breaking my coccyx on the jagged rocks below.

“What I love about climbing is the moment when your movement becomes very precise, and your thoughts focus totally on the task at hand,” says Mike Grimm, owner of Misty Mountain Threadworks, a harness manufacturer based in Banner Elk. Grimm is describing the Zen-like state climbers often find themselves in when the world around them slips away and all that matters is the set of motions that will get them up the mountain.

I would never claim to be Zen-like in any way, but on Cedar Rock, my hands soaked and numb, my body weak from pushing it beyond its normal desk-job/gym routine, I can say that I’m extremely focused. I move slowly up the crack, jamming my feet into the narrow fissure and using miniscule knobs within the crack to pull my body skyward until I reach the overhang. This is the crux of the route—the most difficult move of the ascent. I rest for a few breaths, then reach up with my left hand, gripping the granite lip. Without pausing, I do the same with my right hand, which forces me to lean away from the wall, pushing my body almost parallel with the ground 50 feet below. One foot is smeared against the granite, the other wedged in the crack below the ledge. I have to swing my lower half up, bringing one foot to the ledge near my hands, leaving the other foot dangling. After that, it’s a matter of pulling my body up with my arms and leg, until I can get my elbows and knee resting safely topside.

I’m making the ascent sound much more graceful than it actually was. It was really a fit of jerky, awkward movements, scraping layers of skin off my shins, knees, and forearms in the process. But at no point was I worried about falling. I never questioned the knot, the structural integrity of my rope and harness, or the goodwill of my belayer. I simply acted, moving in a way I think was vaguely reminiscent of The Great Blondin making an omelet above Niagra Falls.

Going Up?

Classic WNC Climbing Destinations

Top-rope routes in Western North Carolina are few and far between. Instead, most routes call for traditional climbing skills, where advanced climbers place temporary anchors in the walls as they climb.

“Trad(itional) climbing can be a bit intimidating, but there are plenty of routes that an experienced guide can safely lead beginners on,” says Ryan Beasley, owner of Rock Dimensions Climbing School. Here are some spots to set your sights on.

Looking Glass Rock | Pisgah National Forest:

The most recognizable of all WNC crags, Looking Glass is a granite dome with rock faces stretching 500 feet toward the sky. The Nose (rated 5.8), a 300-foot climb with expansive views, is perhaps the most beloved route in the state.

Head to the South Face of Looking Glass for top-rope and easier multi-pitch options. The climbs get crowded on weekends, but get there early, and you can cut your teeth on granite routes like the bolted Lichen or Not (5.5) and its neighbor, Short Man’s Sorrow (5.6), which is a perfect path for learning traditional climbing skills.

Cedar Rock | Pisgah National Forest: Across the valley floor from Looking Glass Rock, the granite dome of Cedar Rock is almost as imposing, but gets a fraction of the climbing traffic. It’s a little harder to access, and the routes aren’t close together like on most crags, but guides love this mountain because of the low-crowd factor and easy top-rope rigging. The rock quality on Cedar is typical North Carolina granite, ranging from steep vertical pitches to low-angled sloping routes.

Toads R Us (5.9) is the classic route on Cedar Rock. Tackling the entire multi-pitch might be out of the beginner’s range, but the first pitch is an easier 5.8 climb.

Linville Gorge | Pisgah National Forest: Over the centuries, the Linville River has cut a massive gorge through the High Country that now runs 12 miles long and 2,000 feet deep. And inside that gorge, there’s rock. Lots of rock, ranging from riverside boulders to steep cliff bands with magazine-cover worthy views. The climbing inside the gorge has a “wilderness” feel (appropriate since Linville is one of the most primitive wilderness areas in the state) with nearly no crowds and long, difficult approach hikes. But to the adventurer go the climbing spoils, much of which is surprisingly beginner friendly. Check out The Prow (5.4), a long sloping multi-pitch route with ridiculous views tucked inside an area called The Amphitheater.

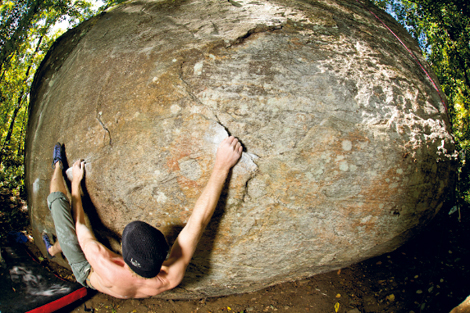

Rumbling Bald | Hickory Nut Gorge State Park: A long, granite cliff band that dominates the northern side of Hickory Nut Gorge, the Bald is popular with Asheville-based climbers, because hundreds of routes traverse the various rock faces and a large collection of boulders offer a variety of climbs for all skill levels.

Table Rock Mountain | Pisgah National Forest: Located on the edge of Linville Gorge in the High Country, Table Rock features a number of beginner-friendly, multi-pitch routes that take climbers 600 feet above the forest floor.

Laurel Knob | Nantahala National Forest: Rising 1,200 feet above its surroundings in Panthertown Valley, Laurel Knob is the tallest granite dome east of the Rockies. The Carolina Climbers Coalition purchased the mountain in 2006, opening its long and difficult multi-pitch trad routes to the climbing world. Beginners should work out the kinks of their trad skills on easier to access crags before trying to send Laurel Knob.

Rock Climbing Outfitters:

Appalachian Mountain Institute

Pisgah Forest

(828) 553-6323

www.appalachianmountaininstitute.com

Black Dome Mountain Sports

Asheville

(828) 251-2001

www.blackdome.com

Climb Max

Asheville

(828) 252-9996

www.climbmaxNC.com

Diamond Brand Outdoors

Arden and Asheville

(828) 684-6262

www.diamondbrand.com

Falling Creek Camp’s Off-season Adventure Programs

Tuxedo

(828) 254-9726

www.fallingcreek.com

Fox Mountain Guides and Climbing School

Pisgah Forest

1-888-28-GUIDE (48433)

www.foxmountainguides.com

Mountain Adventure Guides

Asheville and Brevard

1-866-813-5210

www.mtnadventureguides.com

Pura Vida Adventures

Pisgah Forest

(772) 579-0005

www.pvadventures.com

Rock Dimensions Climbing Guides

Boone

(828) 265-3544

www.rockdimensions.com