Developing from Within

Developing from Within: Old Fort’s Black community is creating outdoor recreational areas to rejuvenate their home

North Cemetery Street in Old Fort doesn’t get much traffic. From Main Street, the road ascends steeply past the graveyard, several modest homes, and a patch of woods. A cluster of vacant houses on a knoll overlook the abandoned textile plant that once anchored the economy of a thriving town in the foothills of the Blue Ridge Mountains. Situated 25 miles east of Asheville, Old Fort has seen its population stagnate at around 1,000 residents, and like many rural communities throughout Southern Appalachia, this town faces an insecure economic future.

Cemetery Street is the name of a predominantly Black neighborhood where Lavita Logan was raised and now lives. Logan worked three decades for the manufacturer Collins & Aikman (now Auria Solutions) and is now the program coordinator of People on the Move for Old Fort, an organization advocating for a more dynamic economic future for the community’s Black residents.

Their economic prospects—and Old Fort’s in general—may not necessarily hinge on the volatile boom and bust cycle of manufacturing. Instead, Old Fort’s fortune may be linked to potential opportunities associated with 42 miles of new recreational trails in the Pisgah National Forest.

At a 2019 community meeting, Logan listened to a pitch by Jason McDougald, a nearby camp director, for support to build a network of multi-use recreational trails in Old Fort’s backyard. McDougald, the executive director of Camp Grier at the edge of Old Fort, is also a leader of the non-profit G5 Trail Collective. He realized there was untapped potential for trail development in the tens of thousands of acres of national forest sandwiched between Old Fort and the Blue Ridge Parkway. But the U.S. Forest Service relies on partnerships with private groups to maintain and build trails. Although other mountain towns such as Boone, Brevard, and Asheville have dedicated trail maintenance groups, the trails around Old Fort were in a maintenance shadow.

Several years ago, McDougald began hosting regular trail maintenance weekends at Camp Grier that were a big success, attracting cyclists from Asheville, Charlotte, and Raleigh. His leadership led to a proposal to build a network of accessible and sustainable trails with the hope of transforming Old Fort into Western North Carolina’s next trail town.

Both McDougald and Lisa Jennings, Pisgah National Forest’s Grandfather Ranger District trail manager, saw a need to invite nonconventional forest users to the table. According to Jennings, traditional interests and user groups—such as hikers, equestrians, conservation organizations, or anglers to name a few—typically have a seat at the table during the development of forest service projects in Western North Carolina. “What we haven’t done before is ask the community-at-large to be involved,” says Jennings.

At the 2019 community meeting, Logan was persuaded that Old Fort could take advantage of the economic opportunities awakened by a trail town. In fact, People on the Move is among the largest financial contributors to the project thus far, sharing grant funds allocated to develop Black entrepreneurship in Old Fort.

Not unlike other small towns throughout Western North Carolina that relied on industry, Old Fort has experienced its share of economic woes, such as the recently shuttered Ethan Allen furniture plant. While the trail project may offer a brighter future for this charming but dusty town, it coincides with a heightened awareness of race across the nation and a focus on the deep economic inequalities facing Black Americans in Old Fort and nationwide. What started as simply a trail project has turned into a remarkable campaign to revitalize a community and to rediscover layers of history buried in the past.

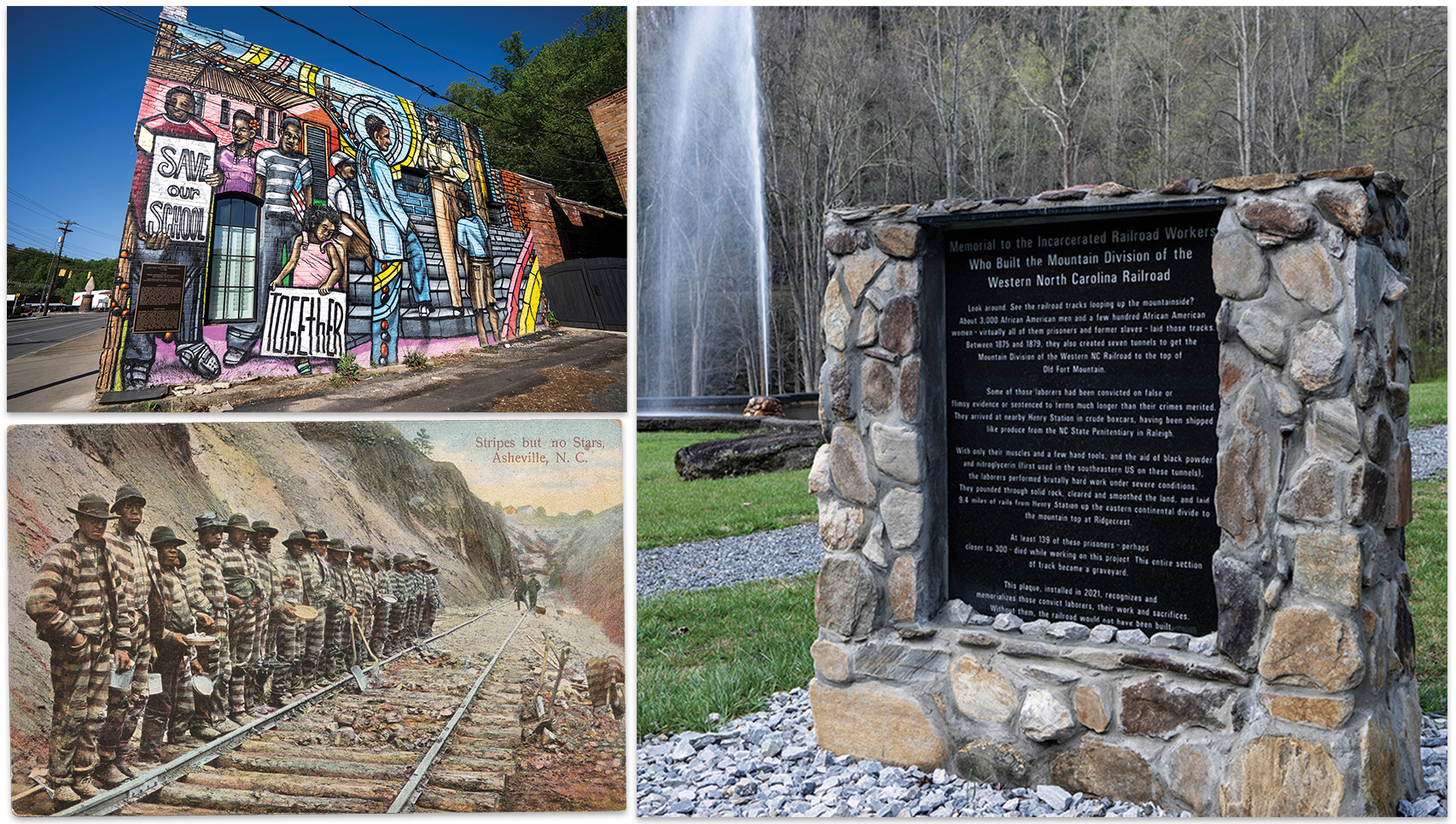

(Clockwise from top left) The mural depicts the 1955 attempt to enroll Black students in a segregated school in Old Fort; On the railroad, working conditions were brutal, and at least 139 Black men and women perished along the way.

BLACK HISTORY IN OLD FORT

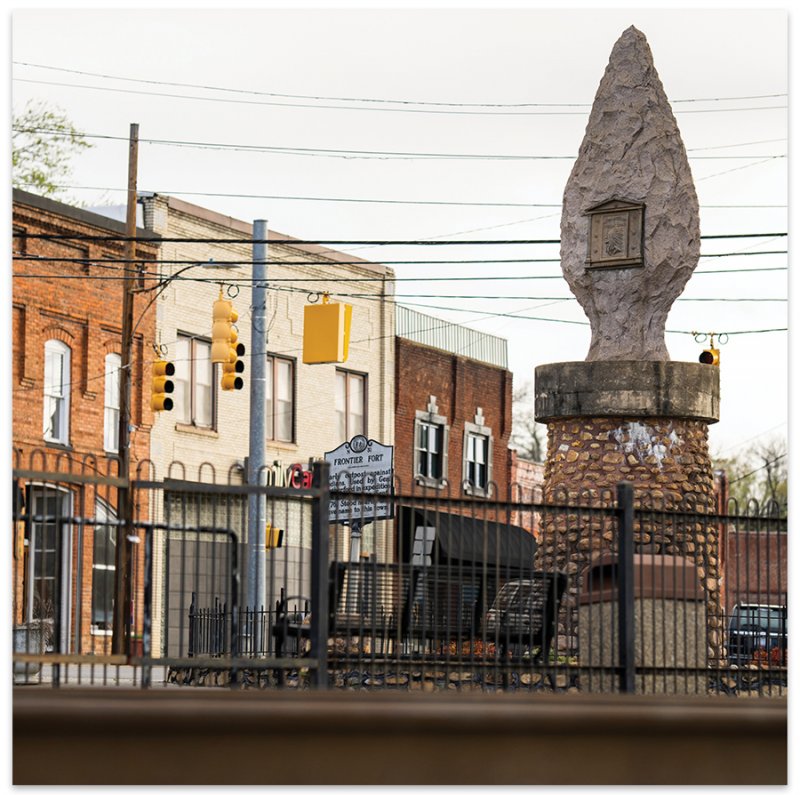

At the center of town, a 30 foot granite arrowhead rests near the site of Davidson’s fort, established by colonial militia in 1756 at the frontier of European migration and Cherokee territory. From this garrison in 1776, American general Griffith Rutherford led an army of 2,400 that terrorized and violently decimated the indigenous communities throughout present day Western North Carolina.

Nearly a century after Rutherford’s campaign, in 1870, the Western North Carolina Railroad arrived in Old Fort spurring prosperity, but with a shocking disregard for human life. In this instance, the burden was inflicted on Black inmates from the North Carolina State Penitentiary. Among the roughly 3,000 prisoners who worked in dangerous and cruel conditions, an estimated 150 to 300 men perished and were covered in unmarked graves between Andrew’s Geyser near Old Fort and Ridgecrest in Buncombe County. Only recently were the forced laborers recognized, by a monument dedicated last fall.

Decades later, the railroad did eventually provide some economic support to a number of Black residents of Old Fort, including Logan’s father and the grandfather of Stephanie Swepson-Twitty. Swepson-Twitty, a lifelong resident of Old Fort, is the President and CEO of Eagle Market Streets Development Corporation, headquartered in Old Fort. Her sense of place in Old Fort, she recalls, was shaped in part by growing up in the Jim Crow era; her family turned away at the door of an Old Fort laundromat in the late 1960s.

The region’s manufacturing boom in the 1970s ushered in an era of relative economic integration in Old Fort. “They needed people to do the work, regardless of ethnicity, class, religion, or race,” she remembers. The economic inclusion of Black workers allowed her family to achieve middle class economic status. Her mother worked on the assembly line at Collins & Aikman and her father was North Carolina’s first black OSHA compliance officer. “The majority of Black families owned cars and homes. We were educated. We finished high school and went on to higher ed,” she says of her 1972 graduating class from an integrated high school in Old Fort.

Then, in the 1980s and early 1990s, the manufacturing economy in Old Fort and across North Carolina’s textile and furniture belt crumbled. In July 1985, the Old Fort Finishing Co., owned by United Merchants and Manufacturing, halted production and unleashed economic upheaval in Old Fort; the 16 acre plant still stands vacant in the town center.

It happened, recalls Swepson-Twitty, in a blink of an eye. Her parents lost their jobs, which was a devastating blow to her father who worked at the plant. “He just never got another shot,” she laments. “He never recovered.”

While the manufacturing bust was felt by all races in Old Fort, it hit the Black community particularly hard. Decades of systemic and institutional racism had created persistent and extreme disparities in income, health, and education between white and Black residents. Today, the net wealth of a typical Black family in America is one-tenth of a white family.

“My parents always had a home, but their ability to improve their home was greatly diminished by the fact that laws associated with lending were very punitive and very tenuous,” says Swepson-Twitty. Redlining—the systemic denial of loans in predominantly minority neighborhoods—constrained property values and hampered the ability of Black families to improve their homes, build equity, or move.

In addition, much of the property in Old Fort’s two predominantly Black neighborhoods, Baptist Side and Cemetery Street, is ‘heirs’ property’. Legally speaking, these are homes and land that lack clear ownership. As a result, acquiring loans and selling or passing land to descendents is tricky. Heirs’ property is among the most unstable forms of property ownership, often exploited and a primary source of lost property and economic opportunity among Black southerners.

Swepson-Twitty attended Montreat College and pursued a career in banking. The organization she leads, the Eagle Market Streets Development Corporation (EMSDC), was crucial to the revitalization of “The Block” in downtown Asheville, a historically prosperous Black hub of commerce and community. She’s focused on a similar model of prosperity for Old Fort. Apart from the EMSDC office, there are no brick and mortar Black owned businesses in downtown Old Fort. The last was Ezra Hamilton Sr.'s cobbler shop, which closed in 1924 but now houses EMSDC’s headquarters.

EMSDC purchased the building on Main Street with a grant from the Dogwood Health Trust to support emerging business in the outdoor, trails, and tourism industry. Known as the Catawba Vale Collective HUB, the “Innovate to Incubate” program intends to engage Black artists and to provide subsidized office and retail space. While they hope to attract people of color, it's a resource open to all. Earlier this year, EMSDC partnered with Kitsbow Cycling Apparel to acquire a 60,000 square feet warehouse in Old Fort with plans to develop a multi-use community center for retail and light manufacturing space for new enterprises.

“The real path to creating generational wealth is ownership,” says Swepson-Twitty. “Either you own your home and it becomes equity, or you own a business and you create jobs. That’s the path to economic security.” Her hope is that Old Fort’s charming downtown will be a destination for future visitors. Part of that traffic may hinge on the draw of trails and outdoor recreation in Old Fort’s vast 70,000 acre backyard of National Forest on the steep slopes of the Blue Ridge’s eastern escarpment.

OUTDOOR EXCLUSION

Already, Old Fort is within striking distance of several legendary trails and cycling routes. Kitsuma and Heartbreak Ridge are big draws for serious mountain bikers. A segment of the Fonta Flora State Trail linking Morganton to Asheville cuts through Old Fort. And there are other promising signs of prosperity centered on tourism. On a recent spring day, for example, a group of two dozen cyclists clad in bright colored helmets and jerseys, parked their road bikes at the Old Fort Ride House operated by California-based Kitsbow, joyfully conversing and downing coffees and bottled waters. Near Kitsbow’s coffee enterprise, Hillman Beer opened in 2019. Another craft beer maker, Whaley Farm Brewery, is slated to open down the street.

McDougald is confident that the additional 42 miles of trail will expand opportunities to a diverse range of users—equestrians, walkers, riders of all abilities, and outdoor lovers. As a climber, paddler, and biker, McDougald admits that some outdoor recreational communities can be exclusive. In technical sports that require special gear, knowledge, and skill, it can be hard to get started or fit in.

Jennings of the Forest Service says they’ve prioritized accessible trail experiences first.

“We could’ve started at the highest elevations with the most rad downhill bike trail, but what we want to do is start with the easy experiences to introduce a new generation of users to the forest, allowing them to grow into the system,” she says. “In the long run, there will be a little bit for everybody.”

Still, the sense of exclusion from the outdoors may be more palpable for people of color.

Dawn Chávez is the executive director of Asheville GreenWorks, a non-profit environmental organization focused on inspiring a new generation of people with diverse backgrounds to participate in the environmental movement.

Chávez, who grew up in the Bronx, connected with the outdoors on family camping trips. As a person of color who didn’t grow up near the woods, she understands why the Black community in Old Fort and beyond may stay clear of the forest and other public lands. During the Jim Crow era, public recreation spaces such as parks, campgrounds, and beaches were segregated. “That has a long impact in communities of color,” says Chávez. “The reason for telling children not to go to the woods may be forgotten, but it’s still a practice passed down through generations. People of color were not welcome and that legacy carries on today.”

Logan understands the reluctance, but holds an enthusiasm for the outdoors that traces back to cheerful memories of swims near her home in Curtis Creek. On summer evenings, her dad took her and other neighborhood kids to swim once he returned from work.

“It’s hard to get Black people in the woods, given the history,” says Logan. “I just want people to take advantage of it. This is our backyard.”

The Black community's participation in a public lands project is a “really big deal,” remarks Chávez. “It’s not something you see anywhere really except in predominantly Black places. And those places usually don't coincide with public lands.”

McDougald says that engaging the Black community was an outgrowth of his observations of Asheville’s path to prosperity, largely from tourism and its access to world-class outdoor recreation.

“We’ve seen Asheville grow and develop and the Black community get left behind,” he says. “We’re in the position to build this from scratch. I hope that this project will engage the local community in being more active and connected to public lands surrounding Old Fort.”

Seemingly everywhere, home prices and rents are rising. It’s easy to imagine that if this town booms, so too will its real estate, crowding out the very people who live here.

“I want us to develop an outdoor recreation economy, but do it in a way that hasn’t necessarily been done before where local entrepreneurs and the community of color have an ownership stake in the town,” says McDougald. “Trails are great. Tourism and economic development are great, but we really want to grow Old Fort’s economy in a way that doesn't displace the folks that have been here for a long time. We want to develop the town from within.”

Chávez says that representation of people of color in the woods “makes a huge difference” and there is a growing movement in Asheville and across the nation to engage minorities in outdoor recreation activities. Those efforts, champions Chávez, should focus on building “authentic relationships with communities of color before an invitation comes. It’s a process to build relationships and trust. That’s the crux of it.”

(Clockwise from above left) Although the process of carving trails will take time, the first section is set to be completed this summer; After a community-wide groundbreaking in January of this year, the trail project is well underway; “Trails are great. Tourism and economic development are great, but we really want to grow Old Fort's economy in a way that doesn't displace the folks that have been here for a long time. We want to develop the town from within.“ — Jason McDougald

TRAILING THROUGH TIME

In January, a ribbon cutting ceremony marked the start of construction of the project’s first six miles of trails. McDougald anticipates the first section of trails will be completed by June of 2022 and continue at a pace of roughly 5 to 6 new miles per year. The G5 Trail Collective is also in the planning stage of the next phase of trail development, which requires targeted archeological work prior to creating new paths.

Two scholars, Jennifer Gates-Foster of the University of North Carolina and Christopher Witmore of Texas Tech University, are leading the work. An expert in Mediterranean archaeology, Witmore has a connection to North Carolina. He bases his summer research from family property in Eastern North Carolina and visits McDougald, a college chum, at Camp Grier.

When asked what he’s unearthed from the forest, Witmore gently swerves the conversation. The work of landscape archeology, he explains, does indeed involve excavation of sites hidden by layers of soil, but his fieldwork approaches the past by taking a more expansive perspective than simply examining a small plot in the forest.

“Recreational tourism often passes over the surface of the past. It doesn’t penetrate down to really understand the nature of the places it goes through,” he says. His work strives to weave together forgotten or neglected objects in the forest into a coherent story as if a tapestry of mismatched fabrics recycled and used over generations.

One such story: Mill Creek Road was once a stagecoach route climbing from Old Fort to Swannanoa Gap that likely followed indigenous pathways 10,000 years in the making.

“That one pathway connects us to an ancient time. We’re interested in connecting people to things of the past, by of course, finding them,” he says. “But also by shaping stories that can connect a community and empowering people to tell their stories and allow them to connect with a place.” From his point of view, those past stories that fall through the cracks may still cultivate a sense of identity and a shared connection.

It’s hard to argue with the premise that knowing the past is essential to the present. Yet, it’s also reasonable to grasp that the erasure of painful memories is, on occasion, intentional. Logan wasn’t aware of the legacy of Black prisoners who built the railroad until their recent recognition. “My parents and grandparents never really talked too much about the past. It just was never brought up,” she says of the Jim Crow era. “They didn't want us to live in that fear.”

Even with that history in mind, Logan still looks ahead. She believes the thoughtful stewardship of a set of trails, of a community and its shared experience, may cut through the tapestry of time. A small community that has managed to endure now forges a new path forward.