Damming History

Damming History: For nearly 100 years, the Ela Dam has interrupted the flow of the Oconaluftee River. But now, a team of locals are restoring the waterway.

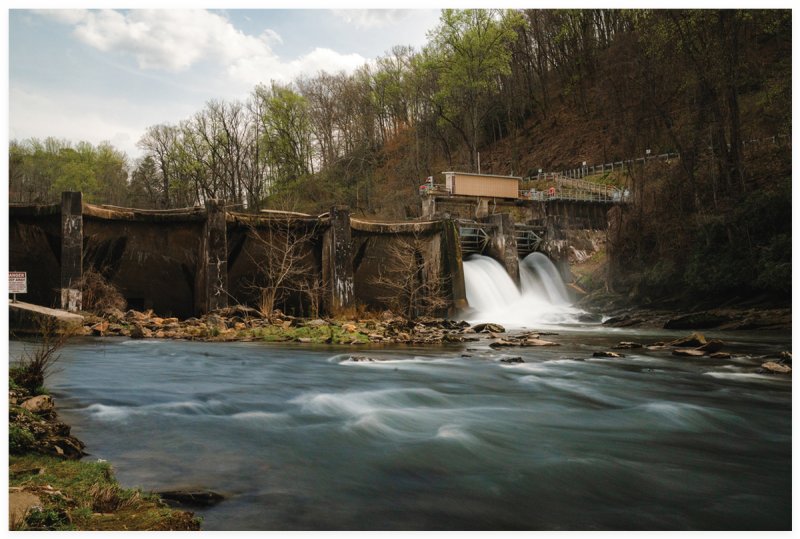

Nearly one hundred years after the concrete was set, the Ela Dam is still helping light homes and charge mobile phones. The core of the dam’s downstream superstructure, four semi-circular recesses each resembling the apse of a church, form the Bryson Reservoir and hold back the waters of the Oconaluftee River near the towns of Whittier, Bryson City, and Cherokee, just beyond the western edge of the Qualla Boundary, the present-day land of the Eastern Cherokee Indian nation.

“It gets uglier every time I see it,” shouts Joey Owle over the roar of water pounding through two spillways following a day of heavy rain last spring. “The Ela Dam has disconnected us for nearly 100 years.” The thirty-four-year-old has a close cropped beard, a glass sphere adorned in each earlobe, and is wearing chinos, a madras shirt and a pair of Vans. Owle, the secretary of agriculture and farming of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians, or EBCI, met with me on a sunny day in March at the dam with Jordan Smith of Mindspring Conservation Trust and Erin McCombs of American Rivers.

“We always joked about getting rid of the dam,” confesses Owle. “It’s just not something we thought could ever happen. It’s still operating, after all.” Until one day in December 2021, Owle picked up the phone to call the dam’s owner, Northbrook Carolina, a division of Arizona-based Northbrook Energy. Owle explained his interest in acquiring the dam, removing it, and healing the Oconaluftee. They were willing to talk.

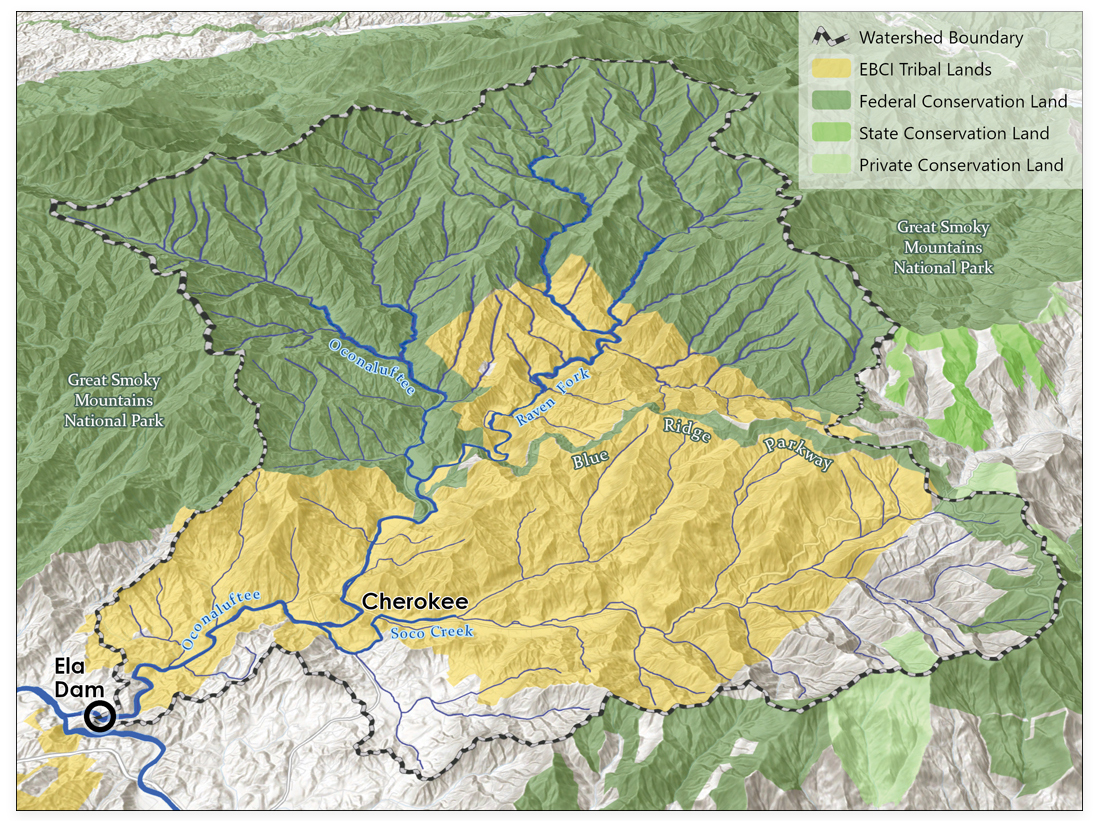

Startled by their response, Owle puzzled over exactly how to buy a dam, dismantle it, and restore the river it interrupted. The answers, it turns out, were supplied by an extraordinary alliance of individuals and organizations, known as the Ela Dam Coalition, that include the current dam operator, Mindspring, and American Rivers. Still in its early stages of design and funding and with plenty of future obstacles, Owle believes the timing is right to remove the Ela Dam and reconnect 549 miles of stream in the watershed. Its looming demolition, says Owle proudly, “is an opportunity for the Tribe to connect our lands to the rest of the world.”

OLD DAM'S A THREAT

According to McCombs, the Southeast conservation director of American Rivers, the Ela Dam is one of roughly 27,000 throughout North Carolina, many of which no longer serve a purpose. While Ela’s turbines still generate electricity, dams can cause harm, too. The structure impedes the river’s natural flow and movement of sediment downstream, alters water temperature and quality, and isolates aquatic populations. In fact, the Oconaluftee River supports a number of listed and rare species, including the sicklefin redhorse, the Eastern hellbender, and the endangered Appalachian elktoe mussel found near the river’s confluence with the Tuckasegee River a half-mile downstream.

“Removing a dam is the fastest way to bring a river back to life,” said McCombs. It allows sediment to spread normally and insects, invertebrates, and fish to flourish. American Rivers is a leader in the movement to remove dams and set a goal to raze 30,000 dams by 2050. In 2022, sixty five dams were removed in twenty states. From a deck along the river’s edge below the Ela Dam, she pointed to a stretch of bedrock on the opposite bank. There, she says, is evidence of a starving river. The bare stone lacking sediment means an absence of habitat for macroinvertebrates, the tiny, spineless creatures, such as crayfish, that filter water. “Sediment is the basis of river life,” she explains.

“We always joked about getting rid of the dam. It’s just not something we thought could ever happen. It’s still operating, after all.” Its looming demolition, “is an opportunity for the Tribe to connect our lands to the rest of the world.” — Joey Owle, Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians

While sediment is a crucial component of a river’s ecology, it can be harmful too, particularly in enormous quantities. On October 3, 2021, Northbrook notified state and federal agencies of an emergency drawdown of the Bryson Reservoir to examine an uncontrolled water discharge through one of the powerhouse bays on the northeast side of the 341-foot-long dam. During the drawdown, a software glitch triggered an accidental gate opening, unleashing a maelstrom of sand and fine sediment that settled in the river bed—in some places several feet deep. Visits by several federal and state regulatory agencies observed the sediment dramatically changed the bottom elevation of the river with potentially devastating impacts to the aquatic habitat.

Among the fish threatened is the sicklefin redhorse. Scientific research suggests their native habitat was significantly reduced due to the construction of dams in watersheds throughout WNC over the last century. With its sharply-curved dorsal fin sticking up like a feather, the traditional method of harvesting the fish is to subdue them using toxins from native plants, and capture them in baskets. While the sediment from the accidental discharge could limit their spawning success in the future, anglers reported the fishery is still intact following stream remediation by Northbrook. Recognized as a distinct freshwater sucker species in 1992, Owle proudly told me the centuries-old Cherokee name for the sicklefin redhorse is jungihtla. “It’s been a staple of our diet for time immemorial,” says Owle.

Now a committed student of the Cherokee spoken language, when Owle was a teen, he cared little about the indigenous name for a fish, let alone a can of paint. “I was ready to leave and I thought I wasn’t coming back,” confessed Owle. “Growing up in a small community, I didn’t see the change I wanted. The opportunities weren’t here.” That may not sound unusual for a teen, however; what’s unique is having such deep ties to a physical place. The Cherokee lands spread throughout the Southern Appalachians, but the heart of the nation is near the Ela Dam and a direct link to 10,000 years of continual human history.

Owle packed up for college and earned two degrees from the University of Tennessee. His desire to experience the world beyond the Qualla Boundary was softened, however, by his recollection of a visit to his middle school by the principal chief of the EBCI at the time, Michell Hicks. “He said something that’s become my mantra: go off, get educated, come back and make a difference,” says Owle. He eventually obeyed his guidance and with his wife returned home after traveling around the world, becoming an extension agent for the Tribe, and in May 2017, appointed to its government.

HELP WANTED

In 2018, Duke Energy was selling several assets in the region including the Ela Dam. Then, the Tribe passed on the opportunity and it was acquired by Northbrook Carolina. Taking on a massive, century-old heap of concrete seemed too daunting a project for the Tribe. But following the sediment release in 2021, Owle and his staff started to think more seriously about the possibility of a river without the dam. Why not? The aging structure would likely require significant costs to mitigate future repairs. Could letting it go be a better option for the operators?

“Everyone brings something to the table. No entity could do this alone. The best projects are done in partnership.” — Erin McCombs, American Rivers

Virginia Commonwealth University historian Gregory Smithers, the author of the forthcoming book The Riverkeepers: The Cherokees, Their Neighbors, and the Rivers That Made America, said the dam was built by the Smoky Mountain Power Company to provide electricity for local White communities and industry, but found no evidence to suggest the power company consulted with EBCI. The damming coincided with the passage of legislation in 1924 granting Native Americans US citizenship. While citizenship was a step towards national inclusion, the Ela Dam was an incision. Regardless of the motives of the designers, Owle said what’s most important is its present and future impact. “The dam blocks off the entire Qualla Boundary,” said Owle. Not only as a physical barrier, but as an impediment to the economic and cultural health of the Tribe. Central to Cherokee spirituality is water. It’s at the core of the Cherokee origin story and is sacred. Water is life, Owle told me. “The Cherokee have always had a strong relationship with water. As an eighteen year-old I didn’t realize what’s here or understand that we have to fight to keep it.”

So when he discovered Northbrook was interested, he scrambled to enlist organizations to help sort out the details of purchasing a dam. Among his first calls was to McCombs of American Rivers. Owle knew he needed her expertise to help navigate a road map for removing a dam, from raising funds to execute its demolition to ultimately restoring the stream. “As a person who spends a lot of time on dam removals, it's still surprising to me just how little data we have associated with these types of project,” admits McCombs. “Everyone brings something to the table. No one entity could do this alone. The best projects are done in partnership.”

Owle, however, had to persuade the EBCI’s twelve-member Tribal Council to back the project. In 2022, the Tribal Council passed a resolution supporting the dam’s removal, but later declined to purchase the dam. Undeterred, Owle recruited Jordan Smith, the executive director of Mainspring Conservation Trust, a frequent partner with the Tribe, to protect Cherokee land and cultural assets. Headquartered in Franklin, the trust works with willing landowners to conserve and steward land in western North Carolina.

$1 PRICE TAG

“This project checks all the boxes of everything we do as an organization, but it’s huge and that comes with big risks,” said Smith, who notes the project isn’t possible without the cooperation and initiative of Northbrook, whose asking price for the dam is $1. Northbrook Carolinas spokesperson Curt Whittaker said the project is a rare opportunity to forgo a relatively small amount of revenue in exchange for a project with such an “outsized environmental and social benefit,” he told me. The dam generates roughly $0.5 million in revenue annually and about one megawatt of hydro-electricity. “The coalition has worked very hard and we respect them,” he says. “This is a beautiful river.”

However, the official transfer of the structure’s ownership to Mainspring awaits funding sources for demolition, restoration, and federal approval to cease generating power. In all, the project has an estimated price tag of $10 million. Thus far, the NC Wildlife Resources Commission granted $800,000 to American Rivers to begin design. And on Earth Day 2023 the coalition was awarded $4 million by the US Fish and Wildlife Service as part of the US Bipartisan Infrastructure Law signed by President Joe Biden in November 2022, which dedicates $800 million to dam removal projects.

“This project checks all the boxes of everything we do as an organization, but it’s huge and comes with big risks.” — Jordan Smith, Mainspring Conservation Trust

As Owle, Jordan, McCombs and I wrap up our conversation below the dam, Owle's young daughter leaps into his arms, smothers her face into his chest, and peeks innocently at me from the corner of her eye.

“This is a motivating factor,” he says with a grin. “You have a kid and all of a sudden the light clicks on. You know, to be able to give her an opportunity along with all the other kids and the future generations. That’s what we’re doing here. This is an opportunity of a lifetime for our people.”

Despite the challenges, the trio are awed by the speed, timing, and the potential impact of allowing the river to flow freely again. “I think our necks are sore from how fast it’s going,” McCombs says. The perks of which will help the region adapt to the climate crisis and biodiversity loss. The project also confronts the legacy of racial injustice. This project, she points out, addresses them all. “What we’re learning in the conservation community is that we have to look at all of these pieces together. The only way we’re going to do that is in partnership.

The Ela Dam cuts a portion of the Oconaluftee River from the Qualla Boundary.

Qualla Boundary

According to Cherokee oral tradition, their ancestors hunted great beasts that roamed the Blue Ridge Mountains. Archeological evidence confirms these accounts based on discoveries of stone spear points and mastodon bones bearing scars from these points dating back nearly 12,000 years. The Qualla Boundary is the present-day home to the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians in Western North Carolina. Its 57,000 acres are just a fragment of the Cherokee landscape that once sprawled across portions of North Carolina, South Carolina, Virginia, West Virginia, Kentucky, Tennessee, Georgia, and Alabama.

The Qualla Boundary is not a federal Indian reservation—land given to a native American tribe by the federal government. Rather, the land is owned by individual tribal members and kept in trust by the federal government. In the 1840s, Tribal members purchased the land following the Trail of Tears, the forcible and violent relocation of the Cherokee people. Current tribal members are descended in large part from about 800 Cherokee who managed to elude the massacre.

Ela Dam Project Partners

• Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians

• Mainspring Conservation Trust

• US Fish and Wildlife Service

• American Rivers

• American Whitewater

• Southern Environmental Law Center

• Northbrook Energy

• North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission

• Water and Power Law Group

• Army Corps of Engineers

• Great Smoky Mountains National Park

• Anchor QEA

• US Environmental Protection Agency

• Tennessee Tech University

• Western Carolina University

Long Man

In 2021, the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians and American Rivers hosted the first Honoring Long Man Day. The day involved clean sweeps of the Oconaluftee River and other streams, but was also intended to share tribal wisdom, or what’s known as traditional ecological knowledge that is passed down over many generations. The EBCI oversees the stewardship of the 57,000-acre Qualla Boundary. Not only does that include management of the land, but it prioritizes the cultural values of its natural resources, such as water, a vital element of Cherokee tradition personified by Long Man, whose head is nestled in the mountains and heels in the sea. A goal of the event is to emphasize the importance of communicating indigenous scientific and spiritual know-how to future generations and to assist land and stewardship managers in solving complex conservation and ecological challenges.