The Climb

The Climb: Savoring the past on Grandfather Mountain’s Classic Trail Corridor

Long before the Southern Appalachians became laced with recreational trails and a popular place for modern hikers, Grandfather Mountain’s western slopes attracted a who’s who of famous scientists and personalities. From the 1700s to today, those intent on savoring the apex of the region’s biological diversity and scenic grandeur have flocked here.

As these various parties of pilgrims picked their way up the “easiest” routes on prominent ridges to the peaks from today’s Banner Elk valley, they marveled at ecological extravagance rivaled by few if any other places in the region. As late as the turn of the 20th century, the US government called the virgin forests still towering on these slopes “virtually primeval.”

Much of that vanished as early 20th century logging finally reached Grandfather’s rocky peaks. Luckily, removing trees from the mountain’s soaring, rugged crest was so difficult that remnants of the rich microclimates and rare species, not to mention ancient trees, remained. A century after most of the major logging ended, as the forests astride the Blue Ridge Parkway creep closer to weaving their crowns together over the road, Grandfather’s slopes are still reclaiming their richness.

Today that gives this distinctive peak claim to being one of, if not the, most ecologically significant summit in the East. Situated where the northernmost part of the South meets the southernmost part of the North, and towering a near vertical mile above the Piedmont so dramatically far below, this one massive mountain is a cleaver of clouds and a birthplace of rivers. The flanks of Grandfather Mountain form the Eastern Continental Divide, dispatching rivers to the Atlantic and the Gulf of Mexico, one of them boasting the greatest vertical drop of any National Wild and Scenic River in the East.

No wonder the western side of the mountain has been a magnet for explorers and adventurers. By avoiding the climb straight up from the lowest adjacent lands to the east, early explorers, and hikers today, start their hikes in what’s called “the High Country.” From the Boone area’s lofty valleys, along the route of NC 105 between Boone and Linville, the last pitch of the mountain’s western defenses are still raved about for ecological and scenic significance.

The Grandfather Profile face is here (both of the main ones), and you can come eye to eye with the old man at one view. So is Shanty Spring, a gushing, legendary “last sure water” point, apparently named for a shack built by loggers. Initials of the local men who struggled up the crags and brought timber down remain scratched onto rocks nearby. Let’s take a look back, then head up the hill.

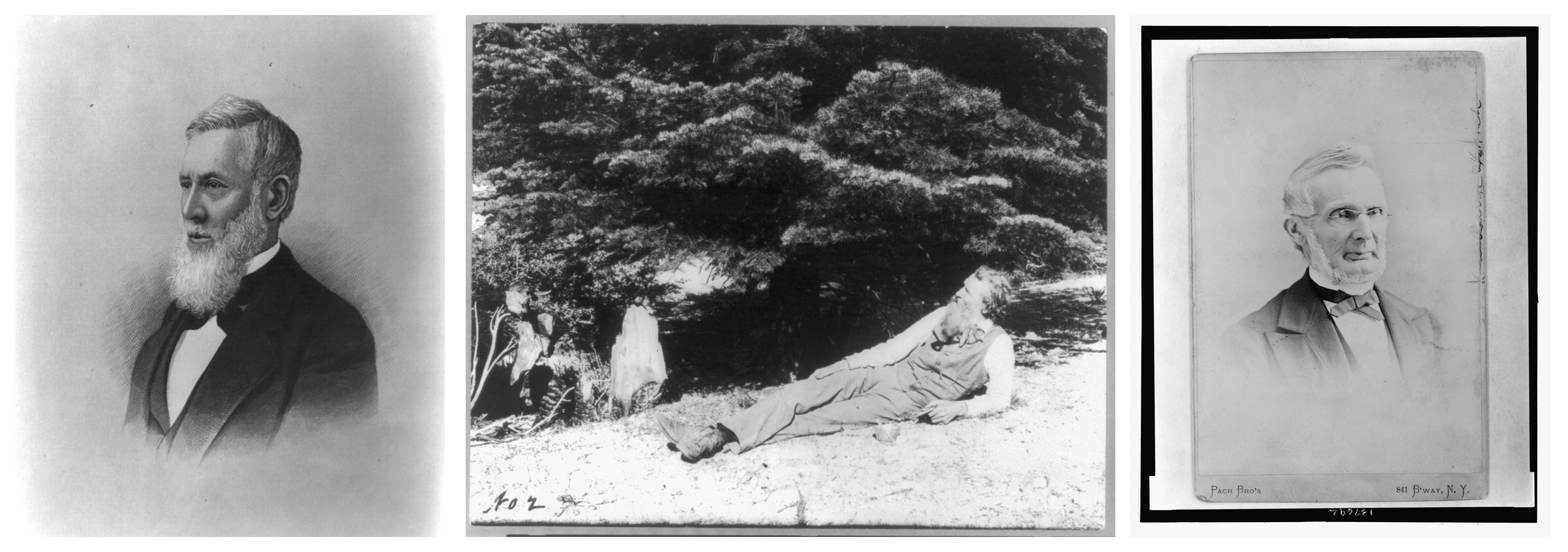

Historic Hikers The 1800s saw visiting scientists, among them Asa Gray and Arnold Guyot (left, right), begin to be replaced by adventurous hikers. One of those was none other than John Muir (middle).

Famous Faces

Most people know Grandfather’s name derives from rocky crags that resemble a man’s face, maybe even an old man when it’s cold and white in winter. More on that later but the list of famous visitors is intriguing too.

Let’s start with the 1794 summit climb by Andre Michaux, perhaps the greatest botanist of the 1700s. The Frenchman’s name adorns many a “new” species he cataloged first and are still found on the mountain. He was a gifted scientist but the gem of this story is his famous flub.

Surely he was amazed at the forest he found, but he was so overwhelmed by the view that he sang the Marseilles hymn and recorded that he’d “climbed the highest mountain in all North America.” Of course he hadn’t, but he’d been to the Alps and he knew what made a mountain look and feel high—the size of the vertical drop-off from the peak to the valley. The vista down that nearly mile high drop would later also recommend a great view from a swinging bridge built in 1952 by Grandfather Mountain private owner Hugh Morton. It was all Michaux needed to see. To this day, Grandfather’s “prominence” over nearby terrain is more reminiscent of the Rocky Mountains than the Appalachians.

Elisha Mitchell, later namesake of Mount Mitchell, also climbed Grandfather. On the summit, he noted that distant Table Rock, “a considerable eminence from Morganton was dwindled down to a Mole Hill.”

The true heavyweight of 19th century American botany, Asa Gray climbed the mountain in 1841 after an arduous journey. From a nearby peak, Hanging Rock, Gray and his guide gazed at Grandfather, “the highest as well as most rugged and savage mountain,” in Gray’s words. On his climb, Gray noted Shanty Spring, one of many who would. He marveled that the forest there was “essentially Canadian.” Gray was back in 1879 but skipped Grandfather—it was almost as inaccessible then as it had been 40 years before.

Another classic scientist, geographer Arnold Guyot, visited Grandfather in the late 1850s mapping the region and noting its remoteness. In Linville Gap (site of NC 105 today), Guyot marveled at the wild setting with barely a rude path. This was the starting point for many early climbers, and it still is today, on Grandfather Mountain’s modern Profile Trail, the rugged route to historic Shanty Spring. Not surprisingly, NC 105, the highway through Linville Gap today, was only built in the mid-1950s.

Late in the 1800s, local writer Shepherd Dugger in a classic book The Balsam Groves of the Grandfather Mountain, added to Shanty Spring’s mystique, calling it the “coldest springs . . . isolated from perpetual snow, in the United States.”

Subsequent explorers intent on fun and travel showed up. New Englander Jehu Lewis climbed the mountain and wrote an 1873 adventure article for The Lakeside Monthly. Famous writer and friend of Mark Twain Charles Dudley Warner barely missed Grandfather on his punishing trip in 1885 but wrote a series of articles for The Atlantic Monthly about it. His companion refused to climb Grandfather because they couldn’t climb it on horseback.

John Muir, Scottish father of America’s National Parks, climbed Grandfather Mountain in 1898 and it was one of the high points of his life. Like Michaux, he burst into exultant song at the summit, raising the eyebrows of his staid Boston companions.

The early 1900s found a dynamic duo of explorers from Johnson City completing a remarkably modern backpacking trip up the west side of the mountain. Don Beeson and Hodge Mathes suffered snow in early September and gazed at the Grandfather Profile, foretelling a main attraction on the later and now closed Shanty Spring Trail and today’s popular Profile Trail.

Margaret Morley climbed the mountain to write her 1913 classic book The Carolina Mountains, recalling climbing ladders on the summit as “the event of the season.”

Author installs sign near Shanty Spring in 1978, replacing a spray painted arrow on the once-overgrown, unmarked trail.

Paths of the Past and Future

Like most of the trails still in use on Grandfather, the old, closed Shanty Spring Trail got it’s start in the early 1940s with Blowing Rock scoutmaster and Blue Ridge Parkway Ranger Clyde Smith. The New Englander marshaled his scouts for trail building not long after the logging. The early explorers’ routes varied, but Smith chose the sharp spine of the Eastern Continental Divide that many traveled where surely a rough, regularly used path already existed. This is the ridge where the scientists marveled that the headwaters of the Linville and Watauga rivers spring from the ground a few hundred feet apart—a truly distinctive start for two rivers that end up on opposite sides of the South.

This was the “sharp ridge” that Asa Gray climbed in 1841 on a “comparatively easy ascent.” It still was when Clyde Smith formalized the rough path in the mid-‘40s. For centuries, the icy water of Shanty Spring has been a landmark. Today, on Profile Trail, it’s still the highest reliable water source.

By the early 1970s, the Shanty Spring Trail and other early paths on the mountain were overgrown, clogged by fallen trees, and hikers routinely got lost. When one died of hypothermia, Grandfather Mountain owner Hugh Morton closed the mountain to hiking. On my next visit, I found no trespassing signs and a security guard.

Luckily, after visiting Morton in 1977 and proposing a backcountry management plan, he hired me to improve the trails, build new ones, and manage their use. The self-sustaining trail program functioned successfully for 31 years, preserving public access until Grandfather Mountain State Park was created.

Sadly, along the way, the Shanty Spring Trail was closed in 1992 when Hugh Morton and a partner proposed to develop the lower land where the trail started beside NC 105. Most of that development was forestalled when The Nature Conservancy and philanthropists stepped in, but a large grocery store and smaller shopping center units were built. Nevertheless the Nature Conservancy still protects the lower acreage where early explorers once trod the route of the old Shanty Spring Trail.

The Profile Trail Takes Over

Knowing development would force an end to the Shanty Spring Trail, Morton dedicated a strip of land along the commercial tract and construction of a replacement, the Profile Trail, got underway. With the route so close to the mountain’s Profile face, the trail climbs from the headwaters of the Watauga River at times steeply to a startling vista of the old man at Profile View.

Along the way, hikers often comment on the stone steps and rock features that carry the path. Hugh Morton’s son Jim and co-worker Kinney Baughman of Boone led the crew during arduous years of creative rock work. Grandfather Mountain has abundant rock, which gave trail builders access to “Grandfather Granite,” fine stone once quarried in the area around the mountain. It’s still visible in a number of historic buildings at the Grandfather Mountain attraction operated by the Grandfather Mountain Stewardship Foundation.

The route of today’s Profile Trail artfully wraps around the still-protected acreage once trod by the Shanty Spring Trail. Nearing Grandfather’s summits, back at the Continental Divide, just below Shanty Spring, hikers are again on the route of the original trail. From there, to the ridge-running Grandfather Trail, a recently improved portion of the original rocky route invites hikers to follow in the footsteps of those early scientists and explorers. Besides being a classic adventure climb, it’s one of the most historic trail corridors in Eastern America.