Better with Age

Better with Age: Blue Ridge Mountain Creamery has ripened from a sideline business into a WNC mainstay

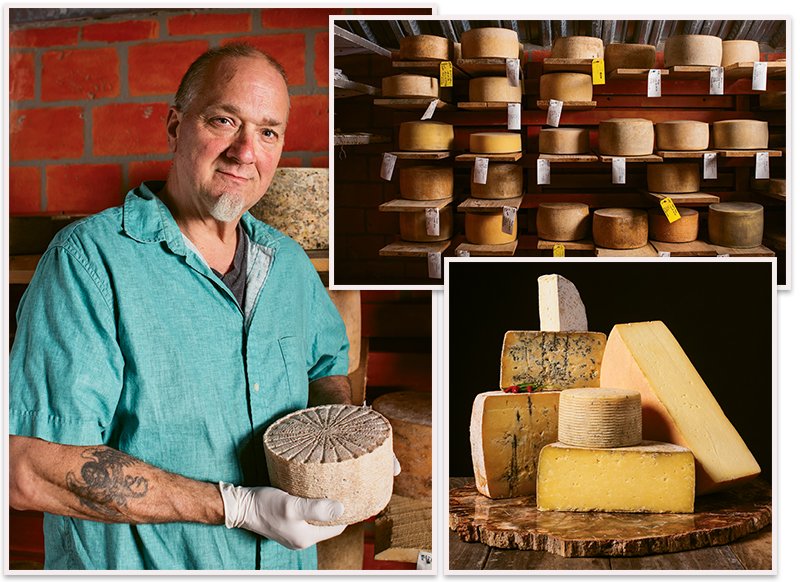

(Left) Victor Chiarizia; (right) Victor Chiarizia’s ever-evolving cheeses are hand-crafted and cave-aged.

“You have to be a romantic to invest yourself, your money, and your time in cheese,” Anthony Bourdain wrote in his 2010 book Medium Raw. That may be the case for most cheesemakers, but Blue Ridge Mountain Creamery’s Victor Chiarizia says he got into it for a different reason. A studio glass artist for over 40 years, he started pondering the prospects of “a normal income” around 2007, he says, and the idea of making cheese appealed to him.

A first-generation Italian American, Chiarizia had made cheese before with his father, a native of the Italian province of Molise, where there’s a long cheesemaking tradition. When he first started thinking about it, Chiarizia says, goat cheese was taking off in Western North Carolina, but no one was really making aged cow’s milk cheeses. It seemed like a niche he could fill. Working with NC State’s extension service, he learned the craft and started producing two cheeses (Ridge Blue and Ugly Baby were the first). Now, not quite a decade later, Blue Ridge Mountain Creamery is producing around 20 varieties of mostly raw, aged cheeses from its Fairview production facility, which shares space with Chiarizia’s glass studio and machine shop.

Mostly sold wholesale or through weekly markets in Asheville, Black Mountain, and Knoxville, the creamery’s cheeses have gained a reputation for quality. In Asheville, The Market Place restaurant makes a seasonal squash soup exclusively with Blue Ridge’s blue cheese, and 5 Walnut’s cheese bar features its products.

Blue Ridge’s cheeses are the product of time-honored—and time-consuming—preparation and aging processes. Left and right, Chiarizia’s production assistant, Brenton Vasconcellos

While aged cheeses may seem exempt from the challenges associated with more perishable varieties, timing is still key. Each week, Chiarizia collects around 300 gallons of milk from a dairy farmer in Mill Spring. Then he and his production assistant, Brenton Vasconcellos, follow what he describes as a mostly straightforward process. The milk is heated to 90 degrees. The pH is tested, cultures are added, acidity is tested, and rennet is added (Blue Ridge uses a vegan rennet). The curd is cut, the whey is drained, and the curd is put into molds. Depending on the type of cheese, it will be salted, wrapped in a cloth or lard, and let to age anywhere from three months to a year. “Cheesemaking is mostly cleaning and waiting,” Chiarizia jokes.

Blue Ridge Mountain Creamery’s cheeses start their aging process either in the “stinky room” (for cheeses such as raclette or Gouda) or another walk-in cooler. Then they’re transported to the cheese cave Chiarizia built himself, where they do what aged cheeses do: ripen with yeast, mold, and bacteria. It’s a risky business—if cracks develop in the cheese, undesirable molds can get in and must be carved out. Cheesemakers must be ever vigilant.

Chiarizia clearly has the patience and the passion for the job. When he starts talking about the cheeses’ flavors—the intensity of rosemary- and oregano-infused Asiago or the rich Gorgonzola—he waxes romantic. While he may have gotten into this rarified culinary art for the income, he stays for the irresistible appeal of a really good cheese.

Blue Ridge Mountain Creamery

327 Flat Creek Rd., Fairview

(828) 551-5739

caveagedcheeses.com