Bear Necessities

Bear Necessities: Learning to live with WNC’s most beloved and misunderstood mammal

COEXISTING

It’s not your imagination: bears and people are getting closer all the time—and there’s a mounting movement to help them get along.

Sonny Pumphrey was 78 years old and working in the yard of his Maggie Valley home one afternoon in November 2018 when he turned around to find a sizable mama bear coming at him, her two cubs scampering behind her. “All of a sudden she run at me at full charge,” Pumphrey said in a remarkable account for Asheville Citizen-Times reporter Karen Chávez. “She reared up with her claws and started to bite me.

“Maybe it was instinct, I have no idea where that came from, but I hit that bear as hard as I could. I was lucky. I caught her right in the nose.” The bear regrouped and kept attacking, but Pumphrey opened up his own can of whoop ass. “I just kept hitting that bear,” he said. “I fought that bear like I would fight a man. I kept slugging her on top of her head, fighting for my life.”

Still, the bear parried, knocking Pumphrey to the ground, grabbing him and shaking him “like a rag doll,” he said. As he crawled to seek shelter in his car, mama loomed over him again—but she was scared off when Pumphrey’s wife, Betty, and the couple’s tiny Yorkie, Bella, came out of the house and raised a ruckus.

After a brief hospitalization and several rabies shots, Pumphrey lived to tell the tale with aplomb. And for all the drama surrounding close bear encounters like this one, in truth, it’s very rare that such incidents come to blows, or to any kind of physical contact between humans and bruins. Yet, there’s no denying that the people and bears of Western North Carolina are going to have to learn to share some space and get along. Fortunately, a multiagency team of researchers is helping the region’s furry and furless inhabitants find ways to do just that.

Population growths

“Of the hundred counties in North Carolina, approximately 41 percent of all phone calls about bears come from Buncombe County,” author Amy Cherrix reports in her 2018 book about the phenomenon, Backyard Bears: Conservation, Habitat Changes, and the Rise of Urban Wildlife. “For now, residents of Asheville seem tolerant of their neighborhood black bears,” she notes before posing the looming question: “Will they be able to coexist with these animals long-term?”

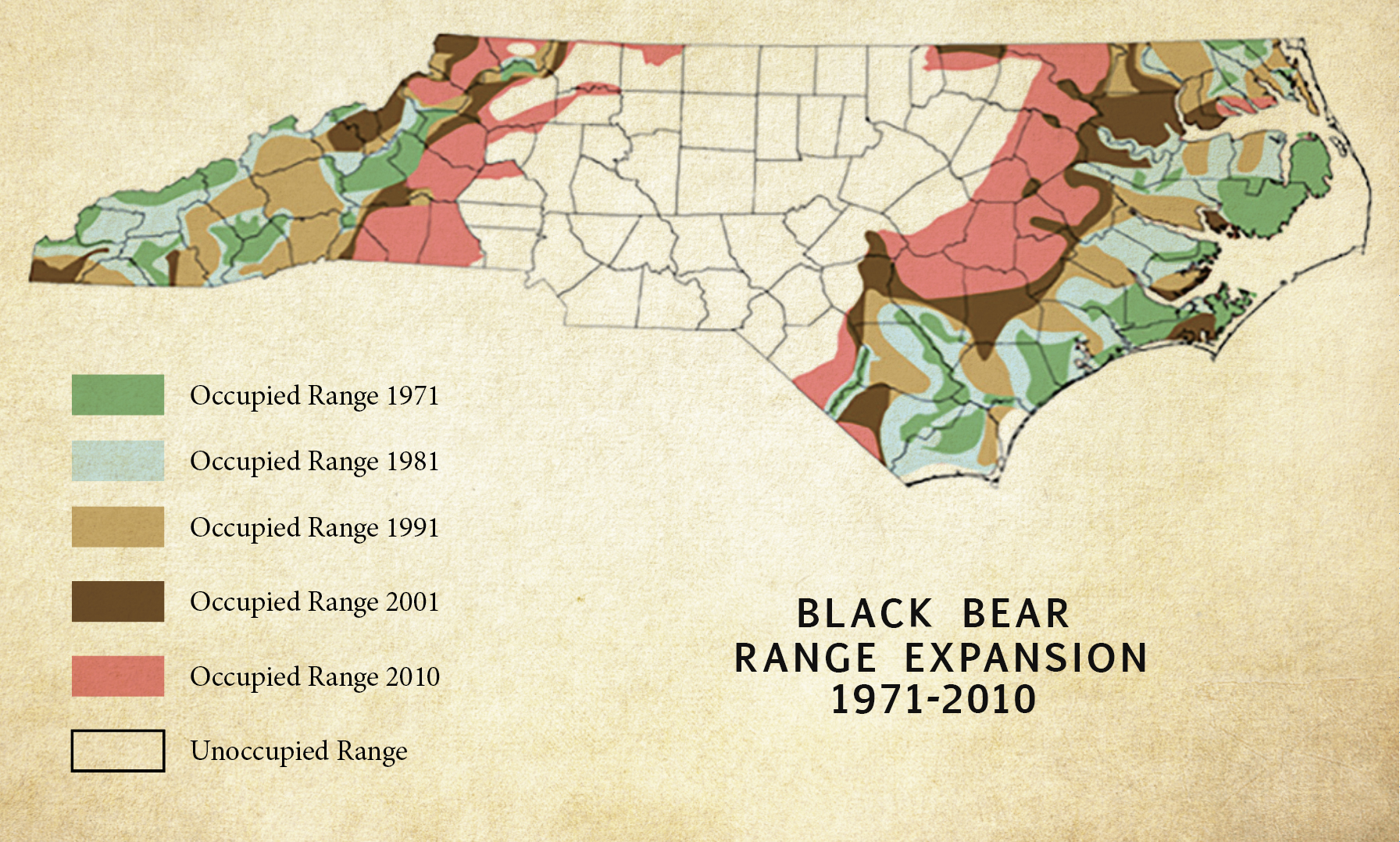

It’s hard to get a precise grip on the number of black bears in North Carolina, but researchers estimate that there are somewhere between 15,000 and 20,000, with a third to one half of them living in WNC. It’s a population that has steadily grown in recent decades, of its own volition, while simultaneously finding some of its native habitats increasingly populated by people.

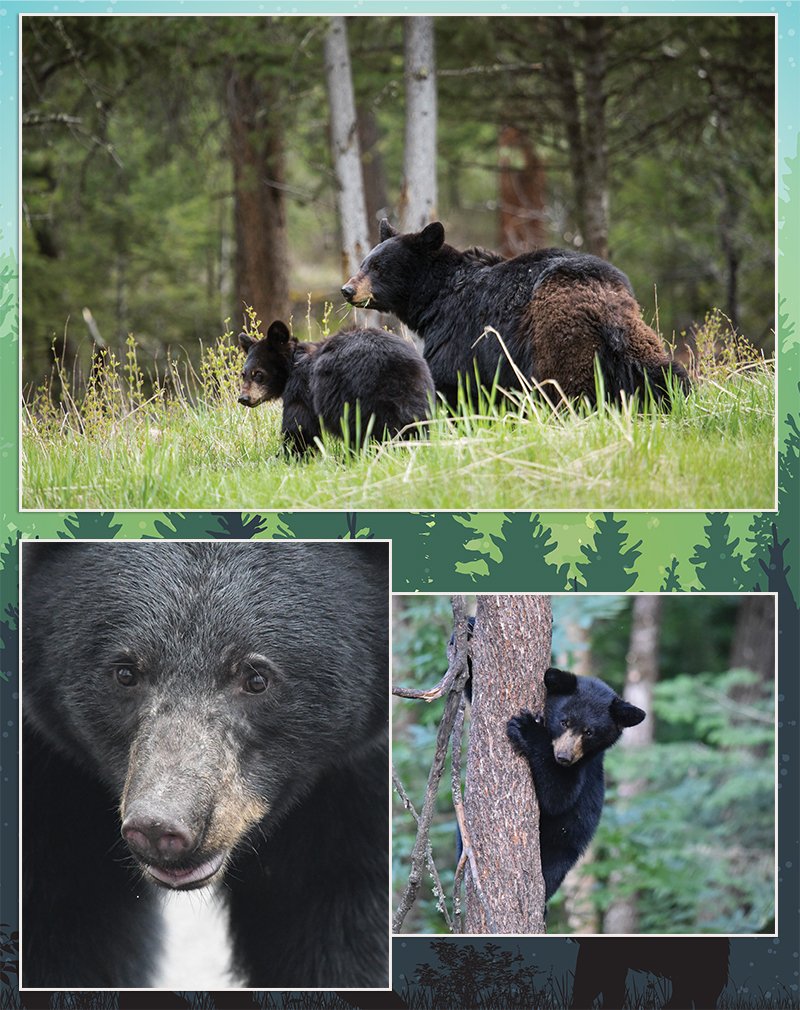

The situation poses a dilemma: local black bears have a fervent fan base among mountain denizens (and, increasingly, city folks as well). They’re a marvel to encounter and watch most of the time, especially when a mama is guiding her cubs into the rigors of life. At the same time, the bears come with a high nuisance factor. They pilfer garbage and pet food, destroy birdfeeders, and even make their way into empty cars in search of snacks—sometimes leaving shredded seats and dashboards behind. They cause the occasional panic and emergency calls, whether or not such a reaction is warranted.

Meanwhile, many mountain-area residents simply want to live in peace with their bear neighbors and are searching for the best advice on doing so. Coming to their aid is a groundbreaking research project, the Urban/Suburban Bear Study, based in Asheville and launched in 2014 by biologists from North Carolina State University and the state’s Wildlife Resources Commission. The project’s first phase lasted four years and studied spacial ecology and population, with an eye toward determining black bears’ survival and mortality rates, movements, and den characteristics. Under the initiative, bears near downtown Asheville were briefly captured, affixed with radio collars, and released to track their movements.

Bear-proofing

Armed with that information, the investigators have begun phase two, which is slated to last through 2022 and focuses on human/bear interactions. Here, the project will share best practices developed by BearWise, a research consortium dedicated to “helping people live responsibly with black bears” (find their main tips later in this article).

Jennifer Strules, an NC State PhD student, is managing the new phase. She’ll work to help two bear-heavy Asheville neighborhoods—Haw Creek and Town Mountain—develop bear-proofing strategies, she says, such as “securing all potential food sources and knowing when and how to report bear activity.”

One of the biggest challenges, Strules says, is grappling with people’s natural affection for this particular wild animal. “There is something about bears that calls to a really deep spiritual sense in people,” she notes. “I think that’s actually a really good thing for bears, in many ways, but in some instances it works against us because we don’t understand that bears are living a life that is mostly separate from humans.”

Bear-proofing, she adds, will necessarily involve some changes in what people do. “If we can work to control human behavior a little bit better and cut down on inadvertent actions that people conduct around their home every day—with trash, pets, birdfeeders, and such—then we go a long way toward living proactively with bears, keeping them wild, and keeping them out of trouble.”

As the study is virtually unprecedented, hopes are high for what it could reveal about how bears interact with humans and vice versa, and what that could tell us about how to share some of the same spaces.

WHAT A BEAR!

Asheville author Amy Cherrix spends a day in the field with the Urban/Suburban Bear Study

On a Wednesday in early May [2018], I get the call I’ve been waiting for. “Jennifer has captured a small bear in one of our traps in East Asheville,” Nick Gould [an NC State University PhD student then managing Phase 1 of the study] says. “You and Steve should get there ASAP. She won’t delay processing that bear any longer than she has to.”

The photographer, Steve Atkins, is on a school field trip with his kids, and he brings the class along to see the bear for themselves.

Jennifer [Strules, a fellow NC State researcher] discovered this new bear on her daily inspection of the culvert traps deployed throughout Asheville. The safe enclosures secure the animal until the biologists arrive during their twice-daily inspections or if the property owner notifies the team of a capture. Each trap is baited with day-old doughnuts and other pastries from a local grocery store. Bears are opportunistic, drawn to any food source they detect. As long as it’s edible, they may eat it, especially sweet foods. Each trap has a trigger with an attached “bait canister” that holds the pastries. To reach the bait, the bear must step all the way inside the trap and pull the trigger with the bait attached to it, causing the door to shut.

It’s spring now, and when the bear study concludes in late August, the traps will be removed to protect any curious animals from accidental capture. While trapping, the team checks every 12 hours for bears, or any other occupants that might wander in, such as raccoons, opossum, and foxes. The trap is empty when we arrive, and there’s a small anesthetized male bear resting comfortably on a red tarp. We watch quietly as the team prepares to examine him. “We were surprised to learn this bear is male,” Strules says, “because he’s the size of a young female, only 109 pounds.” Both wrists of his front paws appear to be disfigured, perhaps due to an injury at some point in his life, but there is no way to identify the cause. For this reason, the bear will not be fitted with a radio collar.

The team’s first order of business is identification. Each new bear must be cataloged, so he is assigned a study number, N157. He is the 157th bear captured by the team. “We are giving him the same numeric identifiers that all bears in the study receive,” Strules explains. “A set of ear tags, a small tattoo on the inside of his upper lip that matches his ear tag number, and a PIT tag.” Due to his small size for a male, he won’t be fitted with a radio collar, so the biologists won’t be able to track N157 remotely. But if they recapture him in the future, they will be able to identify him.

We watch as Jennifer gently examines the bear’s teeth. “He may be a bit older than a yearling, based on how worn the teeth are,” she says.

“Does the bear feel what you’re doing to him?” Atkins’ eight-year-old daughter, Lyla, asks as an ear tag is attached.

“Not at all,” says Strules. “They don’t feel anything, because we put them to sleep first. They wouldn’t allow us to examine them if they were awake.”

Hair and blood samples are taken next. “Hair samples are for genetic testing,” Strules says. “We might learn which family the bear belongs to and who his parents are.” N157’s genetic test might also offer clues about where he came from, or whether he’s related to other bears already cataloged in the study. “The blood samples tell us if the bear carries any diseases. Since these animals live in urban areas, we would like to know if they are carriers of diseases that could harm people, or if these bears are contracting human diseases.”

Strules injects N157 with an antibiotic to help protect him from infection and gives him pain medication to reduce any discomfort caused by these procedures. She rechecks the bear’s heart rate and temperature before measuring his body, paws, and head. His front paws are bent at an awkward angle due to his suspected injuries. They have healed, but improperly, so it makes them difficult to measure. When a person breaks a limb, the doctor sets the broken bone so that it heals in the correct position. N157 had to do the best he could on his own. I wondered if his small size was related to his misshapen paws. But Strules cautions me against jumping to conclusions. We don’t know this bear’s history. We can’t be sure whether his injuries affected his ability to gain weight or find food. It’s easy to make connections that seem logical but aren’t necessarily true. Scientists don’t have the luxury of assumptions. They report only what they can prove.

We say goodbye to N157 as Strules administers the reversal drug, and the team returns him to the trap to safeguard his recovery for the next few hours. When the bear is awake and able to move on his own, Strules will climb on top of the trap and open the door to release him.

For safety reasons, and to reduce N157’s stress level, we won’t be able to observe when he is released, so the students take turns touching his thick fur a final time before we leave. It’s one thing to spot a bear in your neighborhood, but being this close is a once-in-a-lifetime experience.

We are all concerned about the bear, given his injuries, and we are eager to hear how the release concluded. The next day, I receive an email update from Strules. “When I opened the door, N157 tore out of the trap and ran up the hillside. There was absolutely no indication of his handicap. He was able to move at great speed with a completely normal gait and vacated the area in a few short minutes. What a bear!”

The above is an excerpt, reprinted with permission, from Amy Cherrix’s Backyard Bears: Conservation, Habitat Changes, and the Rise of Urban Wildlife (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2018).

WISE UP

BearWise, a network of researchers and wildlife officials from around the Southeast, offers these tips for building better relationships with the critters in our midst. Find out more at bearwise.org.

Who you gonna’ call? Contacts for bearing with encounters

If you and your neighbors follow BearWise’s principles, the experts say, you’ll have significantly fewer of the kind of bear encounters that might call for official help.

Beyond that, you can always contact the likes of your county’s animal control office, located within your sheriff’s department. In Buncombe, the county with the most bear calls statewide, Sgt. Jim Robinson oversees responses to many of those calls. And while he and his officers can help chase off a bear (if they can arrive in time), there’s not much more they can do other than offer good advice from the likes of BearWise.

“If people use their noggins and don’t put themselves in any danger, that’s the big thing,” Robinson says. Don’t be like the local guy who got bit while offering a backyard bear a piece of pizza, for example. If you can’t seek shelter inside your home or vehicle and you feel threatened, he recommends a good noisemaker or, as a last resort, bear spray.

Most often, it won’t come to that. But for bear problems big and small, Jennifer Strules of the Urban/Suburban Bear Study has a key recommendation: call the NC Wildlife Resources Commission Wildlife Helpline at (866) 318-2401. Experts are available there Monday-Friday, 8 a.m.-5 p.m., and they can assist with concerns regarding not only bears but a range of other pesky animals. What’s more, they can route your information to the researchers who are trying to foster a shared environment for humans and bears alike, helping to forge long-term strategies and better results for all.

BEARWISE AT HOME

- Never feed or approach bears. Intentionally feeding bears or allowing them to find anything that smells or tastes like food teaches bears to approach homes and people looking for more. Bears will defend themselves if a person gets too close, so don’t risk your safety and theirs!

- Secure food, garbage, and recycling. Food and food odors attract bears, so don’t reward them with easily available food, liquids, or garbage.

- Remove bird feeders when bears are active. Birdseed and grains have lots of calories, so they’re very attractive to bears. Removing feeders is the best way to avoid creating conflicts with bears.

- Never leave pet food outdoors. Feed pets indoors when possible. If you must feed pets outside, feed in single portions and remove food and bowls after feeding. Store pet food where bears can’t see or smell it.

- Clean and store grills. Clean grills after each use and make sure that all grease, fat, and food particles are removed. Store clean grills and smokers in a secure area that keeps bears out.

- Alert neighbors to bear activity. See bears in the area or evidence of bear activity? Tell your neighbors and share information on how to avoid bear conflicts. Bears have adapted to living near people; now it’s up to us to adapt to living near bears.

BEARWISE OUTDOORS

- Stay alert and stay together. Pay attention to your surroundings and stay together. Avoid walking, hiking, jogging, or cycling alone. Keep kids within sight and close by. Leave earbuds at home and make noise periodically so bears can avoid you.

- Leave no trash or food scraps. Double bag your food when hiking and pack out all food and trash. Leaving scraps, wrappers, or even “harmless” items like apple cores teaches bears to associate trails and campsites with food. Don’t burn food scraps or trash in your fire ring or grill.

- Keep dogs leashed. Letting dogs chase or bark at bears is asking for trouble; don’t force a bear to defend itself. Keep your dogs leashed at all times or leave them at home.

- Camp safely. Set up camp away from dense cover and natural food sources. Cook at least 100 yards from your tent. Do not store food, trash, cooking, clothes, or toiletries in your tent. Store these items in approved bear-resistant containers or suspended in a tree at least 10 feet up and 10 feet away from the tree trunk or out of sight in a locked vehicle.

- Know what to do if you see a bear. Black bears are seldom aggressive, and attacks are rare. If you see a bear before it notices you, stand still, don’t approach, and enjoy the moment; then move away quietly in the opposite direction. If you encounter a bear that’s aware of you, don’t run; running may trigger a chase response. Back away slowly. Visit BearWise.org to learn what to do if a black bear approaches, charges or follows you.

- Carry bear spray and know how to use it. Bear spray is proven to be the easiest and most effective way to deter a bear that threatens you. It doesn’t work like bug repellant, so never spray your tent, campsite or belongings.

Know thy Neighbor

WNC Nature Center’s Brews & Bears

At this fundraising series for Asheville’s WNC Nature Center, local beer and bears are celebrated together. It’s a chance to watch the center’s two resident black bears, Uno and Ursa, take part in an enrichment activity while chatting with bear caretakers and enjoying some of the best of the area’s brews, food, and music. Held once a month in summer, the next event takes place May 8 from 5-8:30 p.m. Visit wildwnc.org for details and tickets, which usually sell out fast.