Baiting a Brookie

Baiting a Brookie: The wildflowers of Western North Carolina’s mountain streams

Ancient History - Mountain brook trout are genetic descendants of Artic Char that once swam in the Gulf of Mexico.

Brook trout are Savelinus fontinalis. Say the name softly. Feel their poetry. They are the trout of spring (fontinalis), the wildflowers of our high Blue Ridge streams. Though indeed they are springtime creatures and members of the Salmonidae family of fishes, brook trout are not trout. They belong to the char genus—Savelinus. The other trout found in Western North Carolina’s mountains belong to two other families: Salmo trutta, brown trout native to Eurasia, and Oncorhynchus mykiss, rainbow trout native to the western U.S.

Char tend to have very dark backs and flanks polka dotted with reds, yellows, and blues. When they spawn in the fall, their bellies turn as orange as maple leaves in autumn. Trout are lighter in color, with rainbows more silvery and browns tawny like burnished gold. The coloration of all three is more vivid on wild fish bred in their streams than those reared in hatcheries and released for us to catch.

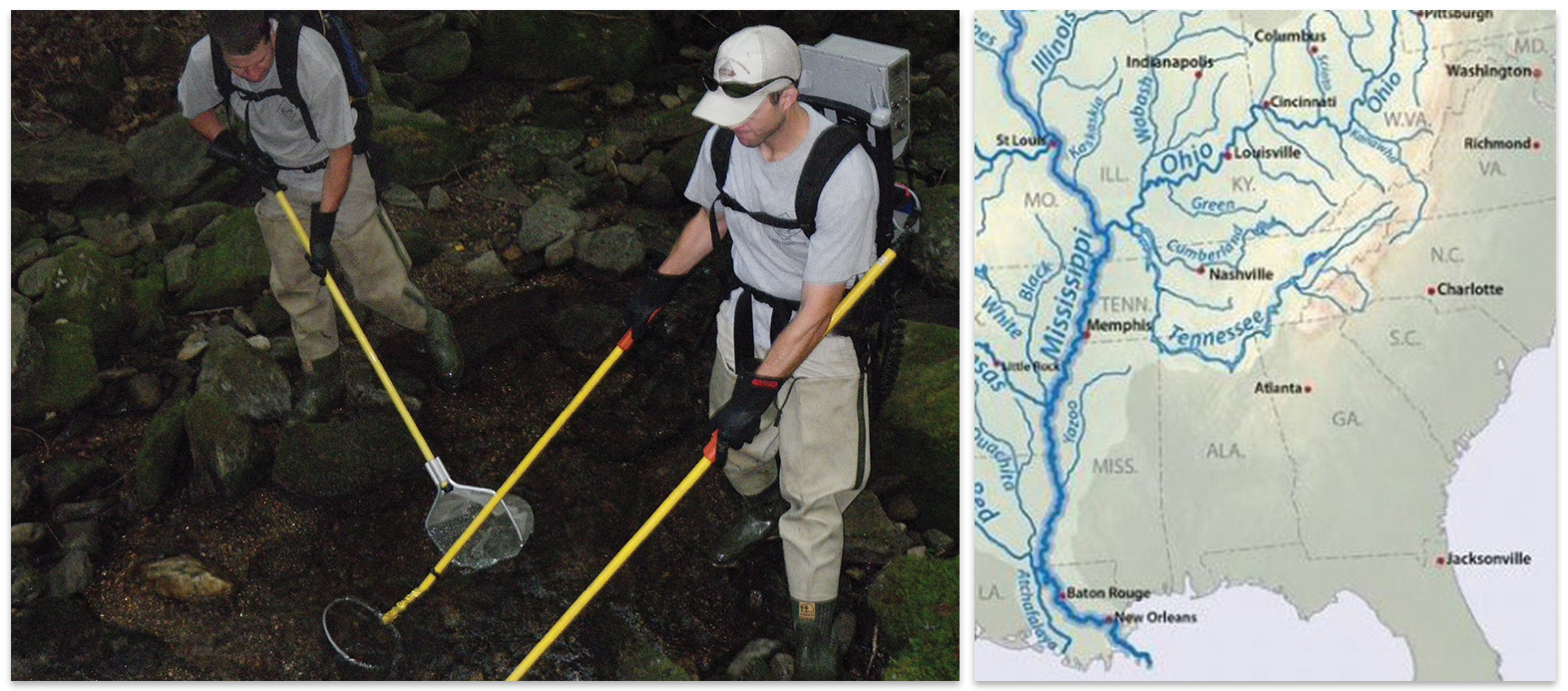

(Left) Keeping Track - Trout biologists use electro-shocking, that doesn’t harm the fish, to determine brook trout populations; (Right) Travel On - To reach creeks high in the Blue Ridge, Artic Char were driven by global warming during the ice ages.

AN UPRIVER JOURNEY

I have to admit that I didn’t always pay much attention to brookies—big browns lunching on hoppers in spring creek cress beds held my passion. But when I drew the short straw and became chair of the Virginia Council of Trout Unlimited in 2006 or so, TU national was running “Back the Brookie”—a campaign to restore brook trout in the Southern Appalachians.

Turns out there are two strains of brook trout, Northern and Southern, native to Appalachia. The dividing line between the native range of the two strains is roughly the New River in Virginia, according to pioneering research by Eric Hallerman, professor in Virginia Tech’s Department of Fish and Wildlife Conservation.

Since I first picked up a spinning rod and cast down Mepps, Rooster Tails and Panther Martins for trout, I’ve known that browns and rainbows have been stocked in the Southern Appalachians for well over a century. But how did the brookies get here? Nobody could seem to tell me.

However, recent genetic research by Hallerman; Jake Rash, coldwater fisheries coordinator for North Carolina’s Wildlife Resources Commission; Matt Kulp, supervisory fisheries biologist for Great Smoky Mountains National Park; and a number of other ichthyologists proves that brook trout descended from Arctic Char.

According to the trio, during the geologic epoch known as the Pleistocene from 2.5 million years ago to about 12,000 years ago, ice sheets flowed and ebbed across North America at least eight times. At the height of each advance, the Gulf of Mexico was as cold as today’s Arctic Ocean and harbored populations of Arctic Char.

As each pulse of global warming between periods of glacial advance heated the Gulf, char were forced to migrate further and further up coastal rivers in search of cooler waters. To reach the mouths of our mountain streams, char swam up the Mississippi, up the Ohio, up the Tennessee, and up the French Broad and Little Tennessee and into their tributaries that rise on the flanks of the Smokies. Think of that journey—roughly 2,000 miles. Brookies have been resident in the Blue Ridge for around 1.6 million years. They, along with perhaps salamanders, may be the oldest vertebrate animal species in the mountains.

To have made that trip, brook trout proved amazingly resilient. Sea-run brookies spend most of the year in the ocean, but swim up freshwater streams to spawn like Atlantic salmon. Coasters in the upper Midwest thrive in the Great Lakes after spawning in tributary streams.

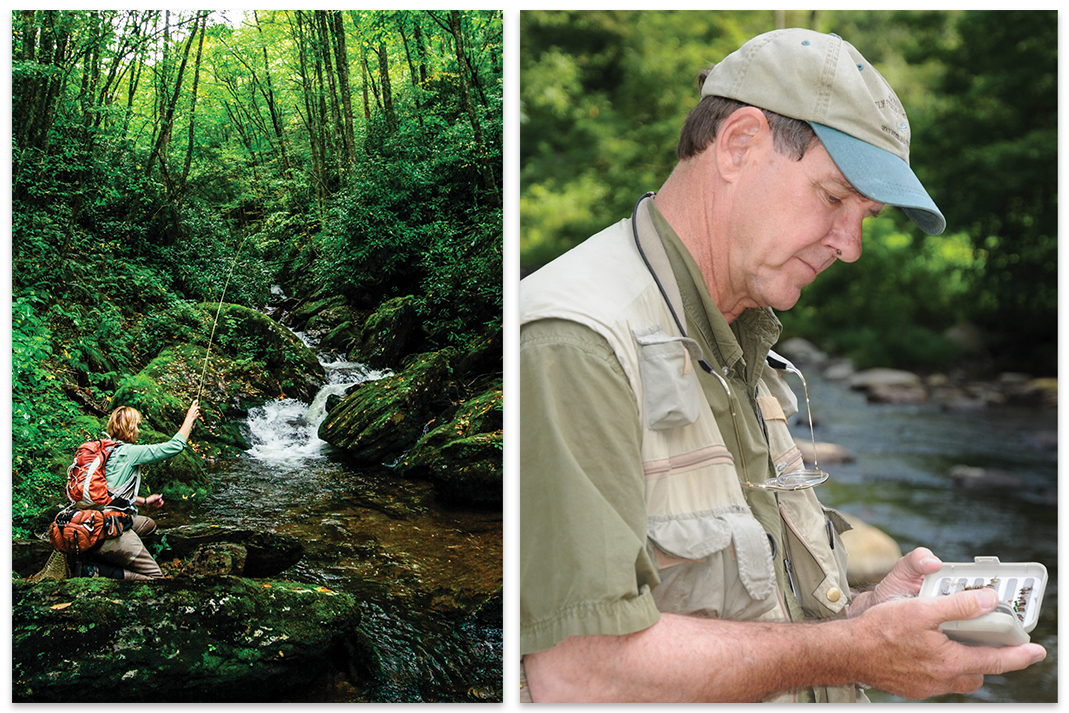

(Left) Hooked - Simons Welter, guide for Brookings Anglers in Cashiers, will tell you that WNC’s highest mountains are veined with tiny unnamed streams favored by native brook trout; (Right) John Ross - Author chooses a fly sure to catch brook trout.

FINDING BROOKIES

Brookies are found in the coldest and purest of our mountain streams, typically above 3,000 feet in elevation. Unlike the most popular trout streams that most of us are familiar with, brookies inhabit narrow runs, not much wider than 50 feet. They favor eddies behind boulders, plunge pools at the base of waterfalls both tall and tiny, and runs where a stream undercuts the bank.

Anglers most often think brookies are only found in high mountain streams. Prior to modern industrial scale agriculture, they also populated spring creeks in limestone valleys. No longer. Spring deluges buried their spawning beds in silt washed from freshly plowed and disced fields. The last spring creek brookie I know of was caught in Mossy Creek near Harrisonburg, VA, in 1968.

I was told, when I began brook trout fishing in Virginia, that during droughts, brookies buried themselves in creek beds waiting for flow to return. That’s not quite true, but they’ll collect in the deepest pools underlain by bedrock, and as they eat what little they can, their metabolisms likely slow down allowing them weather longish dry spells.

During floods, they and other fish move into still waters along the edge or take refuge behind boulders waiting until the stream returns to normal. Even so, many will be flushed out of the creek and it may take several seasons for them to return.

Southern strain brookies were first identified in the mid-1960. Since then, a team led by Steve Moore (now retired), Kulp, and Jim Hebera of Tennessee Department of Environmental Resources, has been restoring Southern Appalachian Brook Trout throughout appropriate habitats in East Tennessee and the Western North Carolina mountains.

The team has been ably assisted by a number of conservation groups, particularly the Pisgah and Land of Sky chapters of Trout Unlimited in North Carolina and the Little River chapter in East Tennessee. Combined, efforts of state and federal biologists and TU volunteers have restored more than 100 miles of habitat for Southern Appalachian Stream Brook Trout.

Brook trout are an indicator species, particularly threatened by increased stream acidity shown by decreases in pH. Acid rain, principally from steam plant emissions, had largely decimated brook trout populations from Maine to Georgia by the 1980s. Reductions in steam plant emissions since the 1990s as mandated by amendments to the Clean Air Act has allowed restoration of brookies throughout the Appalachians.

Stunning Scales - Brook trout are the wildflowers of our mountain streams. Notice their unique speckling of blues, yellows, and oranges.

ANGLING FOR TROUT

No matter where one lives in Western North Carolina, excellent native brook trout fishing is within a couple hours’ drive. Fish the headwaters of the French Broad River, particularly Courthouse Creek above Rosman. Yellowstone Prong of the Pigeon’s East Fork below the falls in Graveyard Fields along the Blue Ridge Parkway is also excellent. Don’t overlook the headwaters of Cataloochee Creek.

These are small waters and fly fishing for brookies is easy. Long casts aren’t required. Just ask yourself this: If I were a trout, where would I wait for the current to bring food to me? Flip your fly into the current so an eddy will swirl it into quiet water behind rock where a trout is likely to hide.

What fly should you use? Stop at a fly fishing shop—there are several, too many to name here, and all know local waters—and ask. Or go online and ask for the “Hatch Chart” for the stream you’d like to fish. Prudent anglers do not fish for brook trout during the fall when they spawn.

A parting thought to ponder. Since each pulse of global warming drives brook trout further and further up their route from the Gulf of Mexico to our highest mountain streams, as the climate continues to warm, how much further upstream can they go?

Cast Off - What to know when fishing for brook trout

- Find the right location: Fishing locations are limited and are often on private property. Make sure to check the North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission’s online map of trout locations first, and keep an eye out for “no trespassing” signs.

- Check regulations: There are six different classes of public mountain trout waters and each has restrictions on what kind of bait can be used, when fishing is allowed, and how many fish you’re allowed to catch. On public mountain trout waters, look for a colorful posted sign to determine what class of water you’re in.

- Obtain permits: For visitors or short-term fishermen, NCWRC offers ten day permits at a low cost. More avid anglers can purchase annual permits or lifetime licenses. Brook Trout are located on the west side of the state, so regardless of the duration of your excursion, make sure to purchase an Inland Fishing Permit.

- Grab your gear: In public mountain trout waters, you can only use a hook and a line, so a rod is your best choice for catching brook trout. Depending on the county and classification of your fishing water, bring natural bait, an artificial lure, or an artificial fly. And pay special attention to the type of hook allowed—some public waters only allow the use of a hook with one point.

To obtain permits, view trout locations, and learn more about fishing in North Carolina, visit ncwildlife.org.