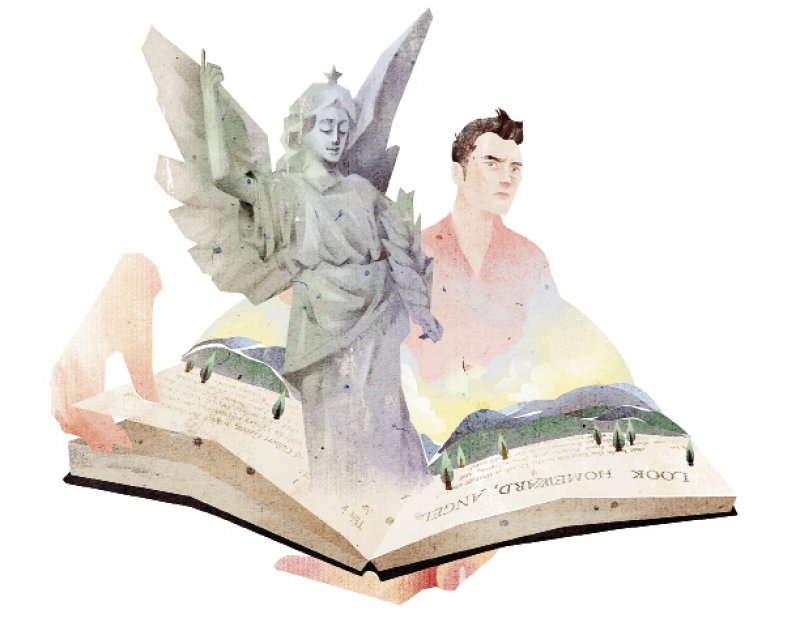

Angel, Come Home Again

Angel, Come Home Again: Touring Asheville with Jude Law, a local writer ponders the weight of Thomas Wolfe

illustration by Dola Sun

Jude Law stood face to face with the replica angel in front of the Asheville Art Museum, and even though I really wanted to, I didn’t ask if I could take a photo. I wanted him to know the angel’s face, to become as informed by its presence as Wolfe was by the real one in both his life and in Look Homeward, Angel. I wanted him to know its serene ferocity, the surging stillness, the airless weight that haunts Wolfe’s work.

Wolfe’s father “wanted to carve the face of an angel,” said Tom Muir, director of the Thomas Wolfe Memorial. Muir arranged the tour for Law, who was in Asheville prepping for his role as Wolfe in the film

Genius, which is now in post-production. It was a fitting metaphor for Law’s process in trying to shape his portrayal of Wolfe. The writer is Asheville’s own angel—drunken, tobacco stained, slovenly at times, yet forever in love with soul and life and time.

As an author and Wolfe historian, my Thomas Wolfe still walks these streets because the lines from his stories unfold in my mind as I stroll. The chiming of the long-gone clock tower pounds the three o’clock hour each day as it does in the first paragraphs of The Lost Boy. He is not lost to me, and now Law is bringing the lost boy back to into the public eye.

Law had never seen the Appalachians, despite playing Inman, who walked up them in the film Cold Mountain. “The mountains were his masters,” I at once quoted aloud as I directed his gaze toward Sunset Mountain from Pack Square. As we moved downhill in the heart of what was once the thriving African-American neighborhood, documented in difficult language in Wolfe’s books, the actor slowed his pace. He took a step forward and then a step back, bending his knees low and jouncing before moving forward again. “You walk differently in the mountains, don’t you?” he observantly asked. I felt the earth move, and knew Wolfe’s love of the mountains would make it into the movie through the way Law walked.

We reached the double-decker bus on Biltmore Avenue, bearing the destination sign “Trafalgar Square,” to which Law commented, “That’s a bit of a ways from home,” and then on to First Presbyterian Church, where Wolfe’s funeral took place. We stood still for a while, envisioning the coffin and the crowd, seeing the city’s grief. That reverence still continues today through a handful of businesses bearing the name Altamont, the author’s fictional name for Asheville.

Walking with Law and listening to his observations and insights into the novels, into Wolfe, into art itself, I understood that this band of actors—Colin Firth playing editor of legends Max Perkins, Nicole Kidman as Wolfe’s lover Aline Bernstein, and Law himself—were stepping into a storm more than roles. When I think of why Wolfe doesn’t appear on reading lists anymore and why people dismiss his work quickly, joking that the sentences are too long, I get the sense that Wolfe was a man beyond what we consider man today. He was immense in more ways than his six-foot-seven height. Here was Law, taking him on, expanding himself to contain someone no one could contain.

Wolfe’s fictionalized biography was a long-form style of writing that only today is finding its footing. With the phenomenon of Karl Ove Knausgård’s nearly 4,000-page novel published in smaller portions, we are now seeing the value of the big book, the long thought, the great reflection. That Genius’ projected release shares the centenary of the National Park system adds an additional air of perfect timing. When Wolfe died in 1938, he was in the midst of researching and writing about 11 parks, having discovered he had written enough about family and was ready to move into a new story: his own. It is a powerful moment for every writer, and Wolfe found in the wilderness an echo to his own voice to tell it with. With the confluence of Knausgård’s literary impact and the National Parks’ milestone, I am moved to believe that we are ready for Wolfe’s voice to come to us once again.

Sadly, none of the filming for Genius took place in Asheville. In this way, the story is strangely complete. Wolfe never liked it here, yet it was all he wrote about. Law came to the mountains to learn what Wolfe could never wholly leave, the place that vexed him to cover every page he could with words about it, a place as massive and mysterious as time itself. A place a lot like Wolfe.

Laura Hope-Gill directs the Thomas Wolfe Center for Narrative at Lenoir-Rhyne University in Asheville.